With the Indians effectively removed from Illinois after the War of 1812, Anglo-Americans felt much more at ease on the land. As they tamed and ordered nature, the land became pastoral and idealized. Though they recognized they had altered the land and lost many animal species, they preferred the comforts of the civilized landscape. Yet though Native Americans left, their influence did not disappear. It persisted in southern Illinois’ nickname, Little Egypt, and William B. Whiteside’s final resting place.

In a March 15, 1817 letter to his cousin William F. Whiteside in North Carolina, William B. reflected on the conditions of Illinois following the war:

We have now peace with the Indains [sic] and people Emigrits [sic] to our country very fast and I am sure we have one of the best Countrys [sic]1

With Native Americans effectively forced out of the state after the War of 1812, the residents of Illinois could civilize the landscape in earnest. Alienation did not disappear overnight, but without a direct threat to their safety, Anglo-Americans felt much more at ease. No longer alienated from the land hiding in stations, they could finally “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth”2 as the “God of nature dictated.”3

William Bolin played a part of the “taming” of the American Bottom after the war. He “replenished” and “subdued” the land as a farmer, and in 1816 claimed a bounty for 16 wolf scalps.4 For pragmatic purposes he likely killed the wolves to protect his livestock, but it also expressed his desire to further dominate nature. Just as he killed Indians for personal security, he killed wolves for agricultural security. The scalping produced two symbols: a wolf pelt that served to commoditize and express mastery over nature, and a scalped wolf body. The latter might have been left behind in the woods; a symbol to the wilderness and to other settlers of who had dominion. It further evoked the stereotype of Indian scalping. The domination settlers once felt Indians held over them was thus projected on the wilderness.

Years of alienation had hardened Whiteside; it was time for him to bring order and stability to the landscape. This masculine need for domination did not end when he left the military, it continued when he served as sheriff for Madison County.5

Increasingly settlers began to associate the land not with hostile Indians, but an Edenic landscape that could support farmers. This is not to say that life was easy or carefree; on the contrary running a farm required a great deal of labor and disease was rampant. Yet the citizens of Illinois no longer had to fear brutal Indian attacks, placing them much less at odds with their surroundings. In 1847, English immigrant Charles Watts wrote to his brother in London, having lived in northern Illinois for about a decade. His letter reveals the greater certainty Illinoisans felt about their place in the land:

Twelve years ago today I was riding on the bosom of the great Atlantic within soundings of the Newfoundland banks enveloped in a thick fog, while the spray was freezing on the head of the ship & rigging, full of hopes, doubts, and fears with a boundless uncertainty before me… I can see before me a good little farm containing some of the best land under heaven, a neat little house, and a comfortable fire side, and industrious, frugal wife, & another little fellow that will help to amuse and keep us busy, and enough of the necessaries that nature requires, inalienable and secure while life shall last, the produce of my own toil and economy.6

Though as an immigrant Watts had different experiences than Whiteside in how he came to Illinois, his experience traveling to an unfamiliar land was similar. Once established on a land no longer beset by Indian attacks, both the Whitesides and Watt became familiar with the land.

Even if some of the original settlers held lasting scars from Indian warfare, their influence shrank as more and more settlers who never encountered Indian warfare like Watts populated the state.

The Edenic view of the land after the 1820s has been frequently studied by other historians. For a review of those studies, see my Historiography.

Yet though settlers felt more at ease after the War of 1812, Indian warfare had left its scars. This can be seen in the widespread panic from the Black Hawk War in 1832, especially in northern Illinois. In Galena, someone fired the alarm gun during the night. Galena resident Horatio Newhall described what followed:

The Indian war assumed an alarming character. On Monday night last we had an alarm, at midnight, that the town was attacked. The scene was horrid beyond description. Men, women & children flying to the stockade. I calculated seven hundred women & children were there within fifteen minutes after the alarm gun was fired… Sick persons being transported on others’ shoulders. Women & children were screaming from one end of the town to the other…

It was a false alarm.7

Though perhaps comical to us in hindsight, the threat of Indians was no laughing matter to the people of Illinois even by the 1830s. The mere mention of an Indian attack unleashed pandemonium among the people. They did not even have to see an Indian in the flesh to panic. With such lasting fears even by the 1830s, it is clear that the need to improve the landscape had not faded.

For Illinoisans, it was not a question of whether the changes they brought to the land were spoiling or damaging nature. While we might think of it in those terms, ecological consciousness was in its infancy in the early 19th century and only had reason to develop once dramatic ecological change had already occurred. As Cronon writes:

Although we may lament the ecological changes we now recognize in the colonial landscape, few people at the time would have seen them as we do. Our concerns in the present will inevitably shape our understanding of the past, which is as it should be – but they also tempt us to misunderstand the past by imposing our own assumptions on people quite different from ourselves.8

Reynolds, for example, argues that all trees in Illinois should be cut down to create prairie for cultivation. He writes, “it is probable that it would be better for the state if there was not a tree in it. There is more money made by the production of corn and wheat than timber.”9 Reynolds thinks of the trees as only having value as commodities. He refers to them as timber, a word that implies their use for construction or fuel. Their worth is not ecological, it is economic. From his economic view, forests are less valuable than prairie, and thus should be cut down. He does not think of an ecological consequence to complete deforestation, that does not matter compared to economic power. Reynolds’ closing words to his memoir show what is supremely important to him: “I close this work hoping and predicting that Illinois will in a few years be the Empire State of the Union.”10

Yet not every settler would have agreed with Reynolds, and many regretted the changes they brought to Illinois. In New England, numerous colonists recognized the ecological damage as it was happening. Benjamin Lincoln railed against allowing livestock to graze in the woods, which resulted in trees being “wantonly destroyed.” Not only was it ecologically destructive, Lincoln argued in the long term it was more expensive to allow livestock to graze in woods than to clear the fields and feed them grain.11

Meanwhile one of Perkins’ main arguments is that settlers in Kentucky had mixed feelings about their “taming of the wilderness.” Many regretted the disappearance of the buffalo and sugar cane, which they had initially believed were so numerous that they could never be totally removed. Yet they were, and settlers admitted that they and others were too wasteful in killing buffalo. As one settler reflected nostalgically, “Kentucky never could have been settled in the way it was, had it not been for the cane and game.”12 Though there are not specific examples from Illinois, no doubt there were Illinoisans with similar opinions.

Even the man who advocated complete deforestation in Illinois, Reynolds, held nostalgia for when animals were plenty in Illinois. After discussing hunting in the early frontier, he writes, “The game, the fowls, Indians and pioneers all seem to sink below the horizon about the same time, and leave the scenes of their existence, pleasures and sports for another generation.”13 Though he misses the days of hunting in his youth, he does not recognize that the reason the “game and fowls” disappeared was because of the pioneers themselves and, to a lesser extent, the Indians. The frontier did not disappear with the animals; the animals disappeared because of the frontier. Even if he missed it, given the choice between the “unspoiled wilderness” and Illinois becoming the “Empire State,” Reynolds would choose the Empire state.

Reynolds might have thought Indians disappeared below the horizon, yet their influence did not leave Illinois when they did. It persisted among those who lost family or friends to Indian attacks and fought against them in the wars. William Bolin lost a brother and participated in all three major fights against the Indians.

Though not explicitly visible, their influence persisted perhaps most strongly in southern Illinois’ nickname: Little Egypt. The name had become widely known by the mid-nineteenth century as the north and south fractured over the issue of slavery. Both Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas referred to southern Illinois as Egypt in their famous debates,14 and the Aurora Beacon feared that “the manufacturing, agricultural and commercial interests of northern Illinois [would] be put into Egyptian bondage.”15

The term had entered popular use throughout state politics, yet few know the Native American origins of the term today. The appropriation of the Mississippi Rivers and the mounds was thus successful in easing fears of an aboriginal landscape, even if most people today recognize the mounds as Native American. Anglo-Americans were successful in taking the land from the Native Americans, becoming the proper cultural inheritors of the “white” civilization that built the mounds.

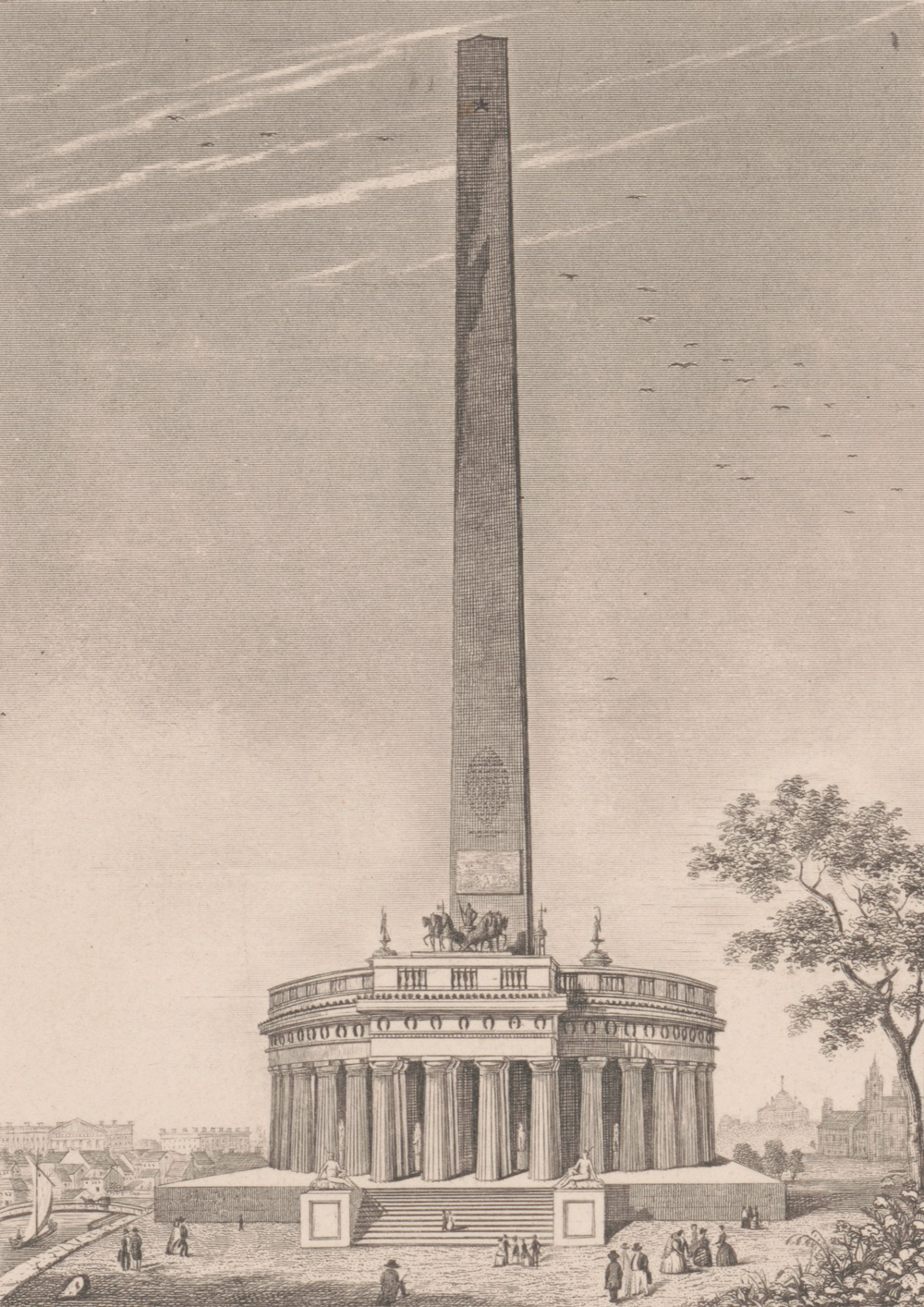

This is visible in the last mark William Bolin Whiteside leaves on the landscape today. Gone are his fields, his home, his fences; features that once held dominion over the land. All that is left is an obelisk, marking the final resting place of him, his wife, and two of his daughters. For reasons I discuss here, it is likely that the obelisk itself was not put up until the death of his daughter, Elizabeth, in 1867. Presumably though he was buried on the hill on his death in 1833 with an earlier grave marker, a place that he likely selected since his wife had died the summer before. The location alone is significant. The crest of the hill offers a commanding view of the landscape, giving a view of the American Bottom and even the Mississippi itself. This allows both an appreciation of nature and the power to stand above it. With a view west, in 1833 one would see the next frontier to be subdued under Anglo-American principles. Perhaps even the hill itself is a reference to the mounds of Cahokia.

Even though the obelisk was likely erected years after his death, it still shows how his cultural –and actual – descendants understood his life and legacy, one defined by an Egyptian influence. The obelisk goes back thousands of years to ancient Egypt, one which had been adopted by the United States in the Egyptian revival, which I first discussed in Goshen Ideology. The Egyptian revival was popular particularly in cemeteries, with the obelisk as a memorial becoming common by 1800. It had become a national symbol, most visible in the Washington Monument designed in the 1840s. The Egyptian association with death is obvious: ancient Egypt is known for mummification and complex immortality rituals meant to preserve life beyond death. Egypt was also known as the land of eternal wisdom and civilization. Egypt was ultimately enduring and timeless – what American culture, and William Bolin, hoped to be.16

The obelisk grave commands the landscape, towering over those who climb the hill to get a closer look. At the top of the hill the obelisk is taller than most humans. Even in death William Bolin exerts control over the land. Evoking a connection to Egypt, the grave portrays itself as the proper inheritor of the land from the Cahokians, itself a monument that, like Egypt, hopes to stand the test of time.

Yet in the 150 years since the last person was buried under the obelisk, nature and time have been working to destroy William Bolin’s last mark on the landscape. Lichen, algae, and fungi have grown on the obelisk’s surface, trapping moisture and secreting acids dissolving the sandstone.17 Wind and rain erosion have chipped away at the corners and smoothed the text carvings, making them more difficult to read. The smaller gravestone belonging to an 11-day-old infant has already lost chunks from its top, making it almost impossible to read today. Were it not for the SIUE campus, quite possibly the obelisk would still be on its side and covered in brush, forgotten.18 Eventually, nature will break down the obelisk completely; leaving no indication that William Bolin Whiteside ever lived there or tried to subdue the Earth.

For how the environment changed in Illinois after the War of 1812, see Statehood Materialism.

For the conclusion, see Land After Whiteside

1. William B. Whiteside. William B. Whiteside to William F. Whiteside, March 15, 1817. Letter. Part of the Whiteside genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

2. Gn 1:28 KJV.

3. Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The Territorial papers of the United States: Volume XVI, The Territory of Illinois 1809 - 1814. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1948), 188 - 9.

4. Records for 1816 are available because they were still on file in the Madison County Courthouse in 1882. B. E. Hoffmann, “Chapter IX: Civil History,” in History of Madison County, Illinois, Illustrated, With Biographical Sketches of Many Prominent Men and Pioneers, (Edwardsville: W. R. Brink & Co., 1882), 123.

5. W. T. Norton, ed., Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois, and Its People, 1812 to 1912—Volume 1 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1912), 134.

6. James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 6.

8. William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, 20th Anniversary Edition. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003), 178.

9. John Reynolds, My own times: embracing also the history of my life (Belleville: B. H. Perryman and H. L. Davison, 1855), 44.

10. Ibid., 600.

11. Cronon, Changes in the Land, 146.

12. Elizabeth A. Perkins, Border Life Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 77.

13. Reynolds, My own times, 88.

14. “Text Search of Political Debates Between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas,” Bartleby.com. (accessed March 21, 2016).

15. Drew E. VandeCreek, “Politics in Illinois and the Union During the Civil War,” Southern Illinois University Libraries. (accessed March 21, 2016).

16. Richard G. Carrott, The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning; 1808-1858. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 81 - 82.

17. “Cleaning,” Chicora Foundation Inc. 2008. (accessed March 21, 2016).

18. John Costopoulos, "Graves tell Illinois history," The Alestle (Edwardsville, IL), April 28, 1972.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.