The relative peace between Native Americans and Anglo-Americans started breaking down in 1809. Though the British had officially left the Northwest Territory, they still projected power from Canada through Native American allies. The British hoped to maintain the lucrative fur trade, which American agriculture threatened. They were not interested in settling the territory themselves: they hoped to create an Indian buffer to halt American settlement and prevent Americans from gaining control of the Great Lakes. For their part, Indians recognized the threat Anglo-Americans posed to their sovereignty, so the alliance was formed.1

With British support and arms, Indians resumed frequent raids against Anglo-American settlements in southern Illinois, united behind the leadership of Tecumseh.2 Many settlers were killed.

Adding to the terror of the Anglo-Americans were two natural phenomenon in 1811 seen as a harbinger of war: a comet and the largest earthquake in recorded history east of the Rocky Mountains: the New Madrid Earthquakes. Anglo-Americans felt as if nature itself was turning against them.

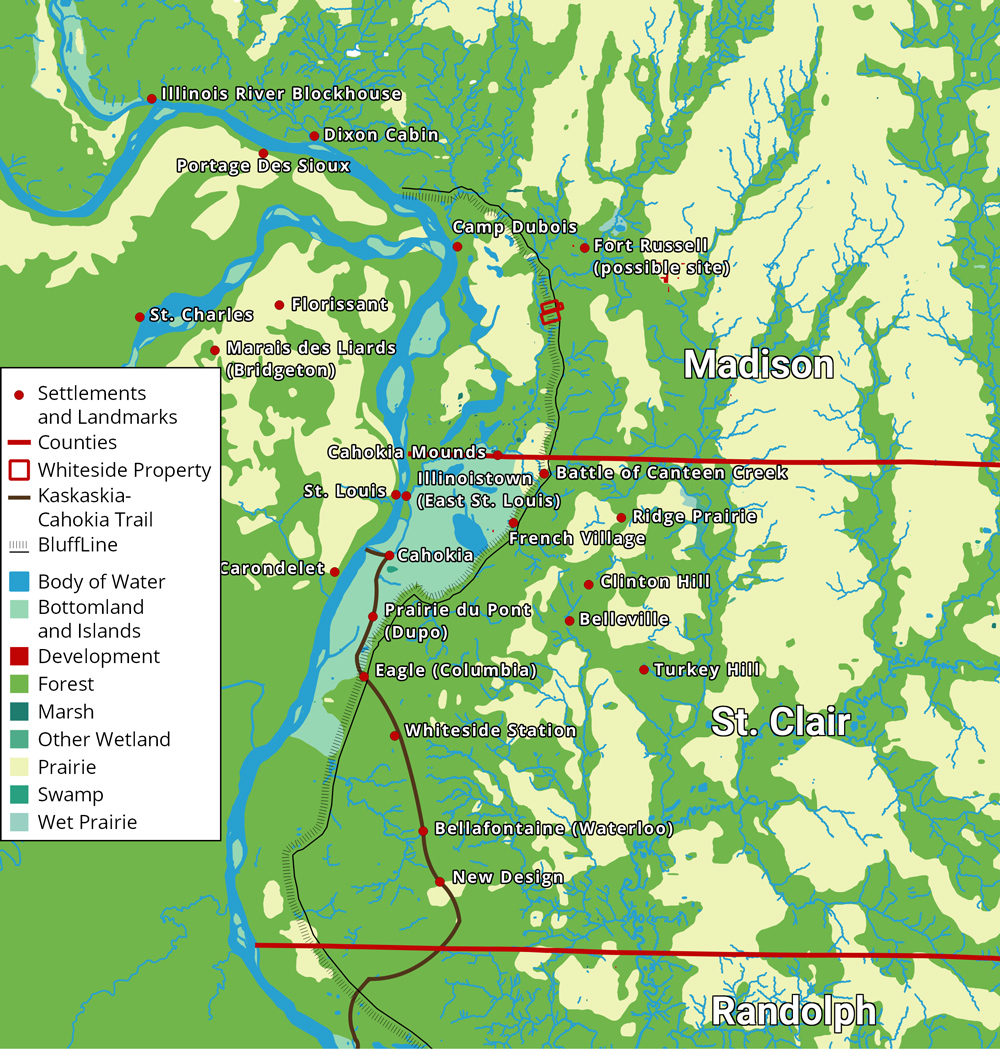

While unnerved by both natural and Native threats, Americans did not back down. In 1811 Congress authorized the creation of 10 companies of mounted Rangers to protect Anglo-American settlers. Four Ranger companies were charged to protect Illinois. William B. Whiteside was appointed captain of one of these companies, and his cousin, Samuel Whiteside, was appointed captain of another.3

Settlers meanwhile returned to blockhouses and forts for protection. Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards was an active participant in the war, leading troops into battle. In 1812 he ordered the construction of a fort in the Goshen settlement to serve as his headquarters, today in northwestern Edwardsville. Named Fort Russell, it was the strongest and most impressive fort in Illinois. Because the Goshen settlement was one of the most northern settlements, Fort Russel was the launching point of assaults into Indian and British territory in northern Illinois.4

In the east, the United States and Britain neared war for additional reasons. Chief among these was the rise of Napoleon and resulting conflicts between the American and British navies regarding trade and impressment of American sailors into the British navy. Thus Congress officially declared war on June 18, 1812.5

After two years of attacks and counterattacks, neither side gained a decisive victory in the west. Though Native American raids became less frequent, Anglo-Americans had failed to force Britain out of the northern Mississippi Valley. Their primary victory was the capture of territory around modern-day Peoria. However, Britain was weary of war with Napoleon, and Indian strength was diminished after American troops killed Tecumseh in 1813 and their alliance broke down. Raids had failed to dislodge Anglo-Americans from southern Illinois. Illinois was largely spared from the massacres and bloodshed in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Indiana. The most significant site of American bloodshed was Fort Dearborn at present-day Chicago, in which about 65 Americans in the fort were killed.6

The resulting peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States, the Treaty of Ghent, did not result in any territory changes. Britain kept Canada but gave up the prospect of an Indian barrier. Native Americans were left on their own to deal with Anglo-American settlement. Without British support, they never again were a serious threat to Anglo-American control of Illinois, even during their last ditch effort in the Black Hawk war 18 years later. A series of treaties between American authorities and Native American tribes during these 18 years gradually ceded away Indian sovereignty in Illinois. Many migrated west across the Mississippi or north to what would become Iowa.7

1. James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 89 and 134.

5. U.S. Congress, “An Act Declaring War Between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Dependencies Thereof and the United States of America and Their Territories,” 1812.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.