The goal of this page is to provide a general historic background to frontier Illinois before I go into more detail on Whiteside and his fellow settlers’ relationship with nature. For more details on Illinois history prior to Anglo-American settlement, see Land Before Whiteside.

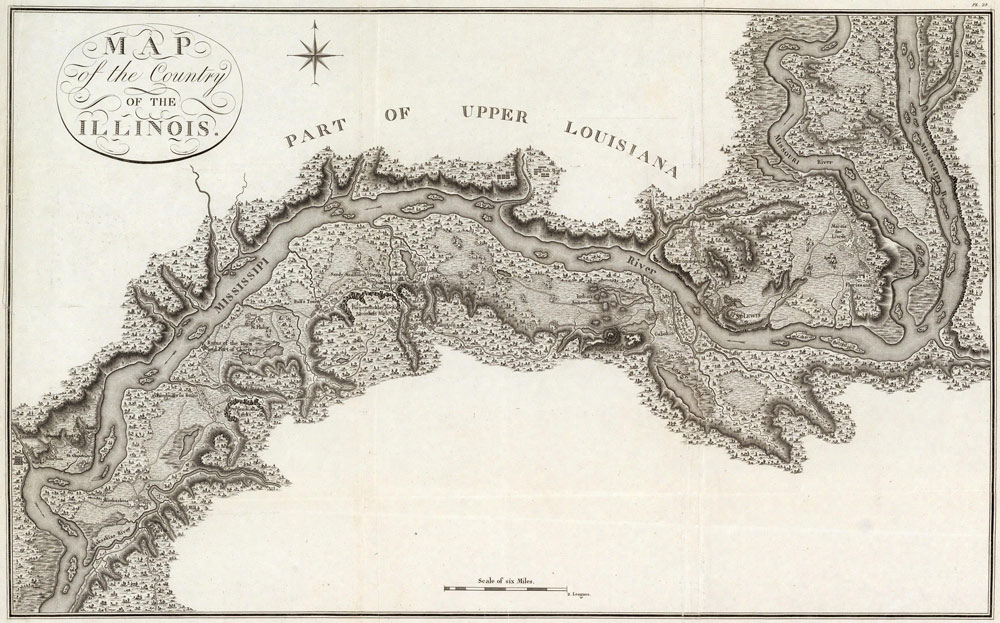

The first humans in Illinois arrived around 8000 B.C. Over time, these people developed agriculture alongside hunting and gathering. Around 1000 A.D., North America’s most complex civilization north of Mexico developed along the Mississippi, centered in the city of Cahokia. This Mississippian civilization is most known for its large mounds of earth, with Cahokia’s peak population estimated to be around 10 to 20 thousand.1 Yet for a variety of uncertain factors, this civilization had collapsed by European contact in 1673.2

A variety of Indian nations took the place of the Mississippians. The Illini Confederacy of as many as 12 different Native American tribes occupied territory along the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers in the western half of Illinois when the French arrived in the late 1600s. As the Illini population and territory shrank due to a combination of European diseases and warfare with other tribes, their former territory was filled in by various groups including the Iroquois, Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, Powatatomi, Sioux, Chickasaw, Shawnee, and Quapaw.3

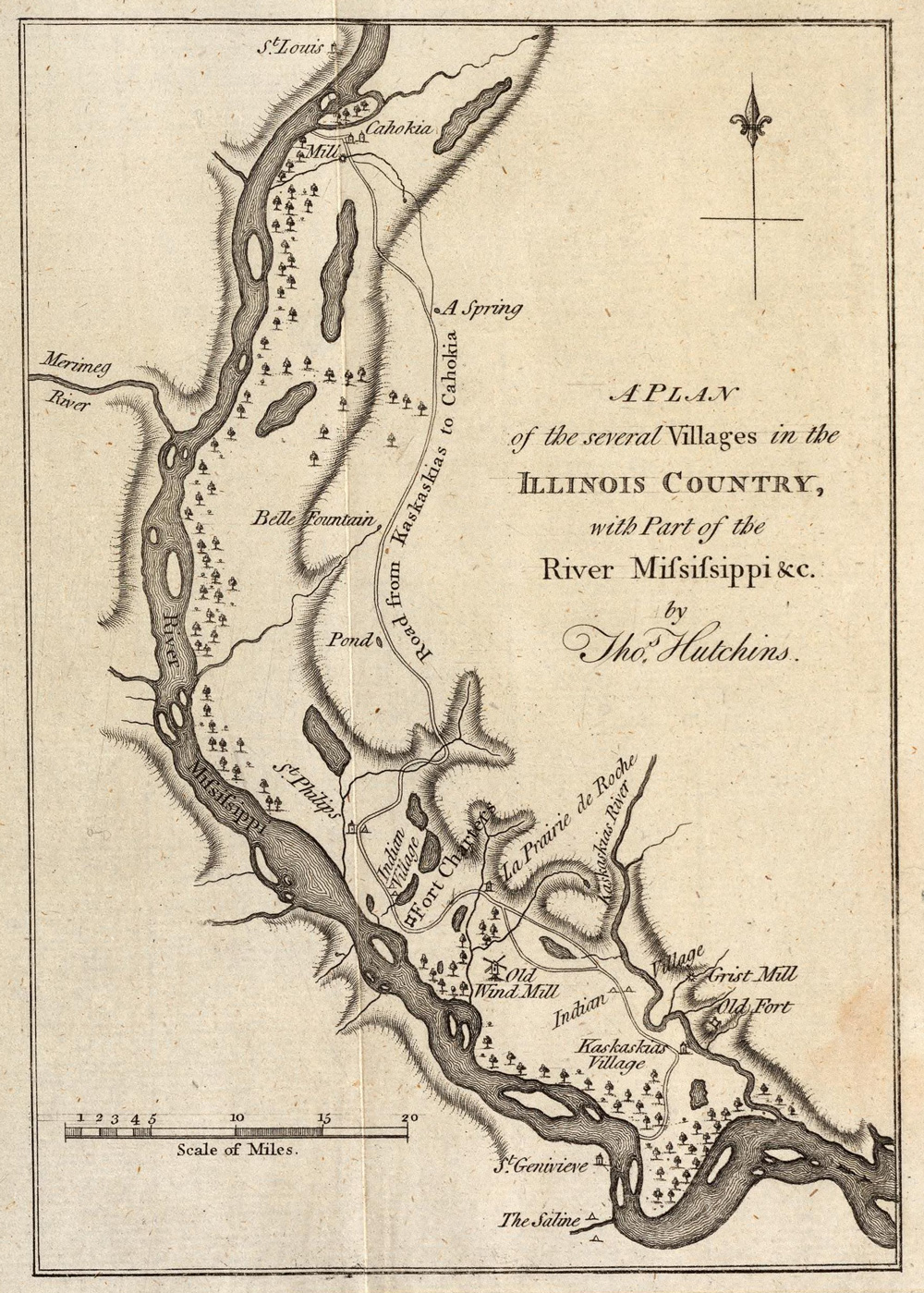

Unlike the original 13 British colonies, the first Europeans to arrive in what would become Illinois were the French, who established trading posts and villages along the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers beginning in the late 1600s as an extension of their older settlements in Canada. At their peak in 1752, the French population reached 1,380, about 40 percent were enslaved Africans.4

As a general rule, French and Indians coexisted far more peacefully than British and Indians, bound together in the fur trade. As a result, a borderland developed between the French and Native Americans. French men frequently married Indian women who converted to Catholicism, as Native American culture and customs underwent a great transformation. Some of the French too adopted Indian customs.5 The children of French and Indian parents became known as Métis, the human manifestation of the mixing of French and Indian people.6 Also among the French were enslaved people, both Indian and African.7

The French government claimed large areas of North America. In 1682, Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle claimed the entire watershed of the Mississippi in the name of King Louis XIV, naming the territory Louisiana. Yet their rule only lasted 81 years. France’s loss of the Seven Years War, the French and Indian War in North America, lost them Louisiana. The Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans was ceded to Spain, while the eastern portion was ceded to Britain.8

British rule was even briefer and fraught with problems. French people still living along the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers did not vanish when Britain and Spain took over. Both governments failed to establish significant control over the former French territory. Spain essentially administered their territory without significant investment, giving French residents a degree of autonomy and maintained existing trade relations with Native Americans. Spain largely saw the Louisiana Territory as a buffer between British colonies and their colony in Mexico.9

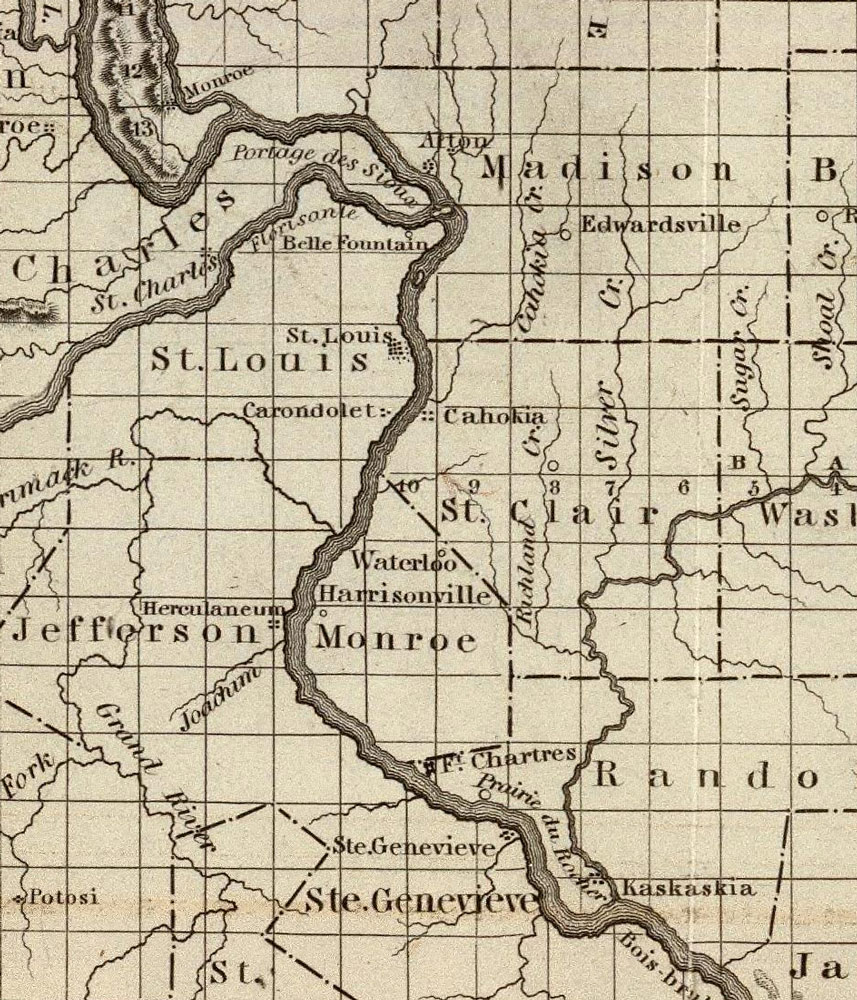

St. Louis was founded during the transition from French to Spanish rule on the western side of the Mississippi. In 1763, Pierre Laclède and his stepson and clerk Auguste Chouteau were sent to choose the site of a trading post to trade with Native Americans along the Missouri River. They choose a site near the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi on an elevated bank, protecting the trading post from flooding. Today this is the site of downtown St. Louis. Though founded under French orders, the residents of St. Louis learned that they had become part of Spanish territory in 1764. When Britain formally sent leaders to Illinois in 1765, a number of families in Illinois French towns migrated across the Mississippi to St. Louis, preferring Spanish rule.10

France and Britain were bitter rivals in the 18th century, leaving many Illinois French fearful of British rule. Spain and France had more amiable relations, leading many to migrate across the Mississippi. At times the British attempted to force the French out of Illinois, but colonial bureaucratic disagreements, British debt from the Seven Years War, and French stubbornness made this goal insurmountable, and ultimately the British, like the Spanish, only sent official dignitaries to various settlements.11 The British even tried to prevent Americans in the eastern colonies from migrating across the Appalachians, in part to avoid having to govern their new territory. Yet despite their efforts, Americans migrated into the Ohio River valley, particularly into what would become Kentucky. As they pressed into Indian territory essentially free from the constraints of the law, Anglo-Americans and Indians engaged in brutally bloody warfare in the Ohio River Valley, which historian Jay Gitlin called “state-sanctioned ethnic cleansing.”12

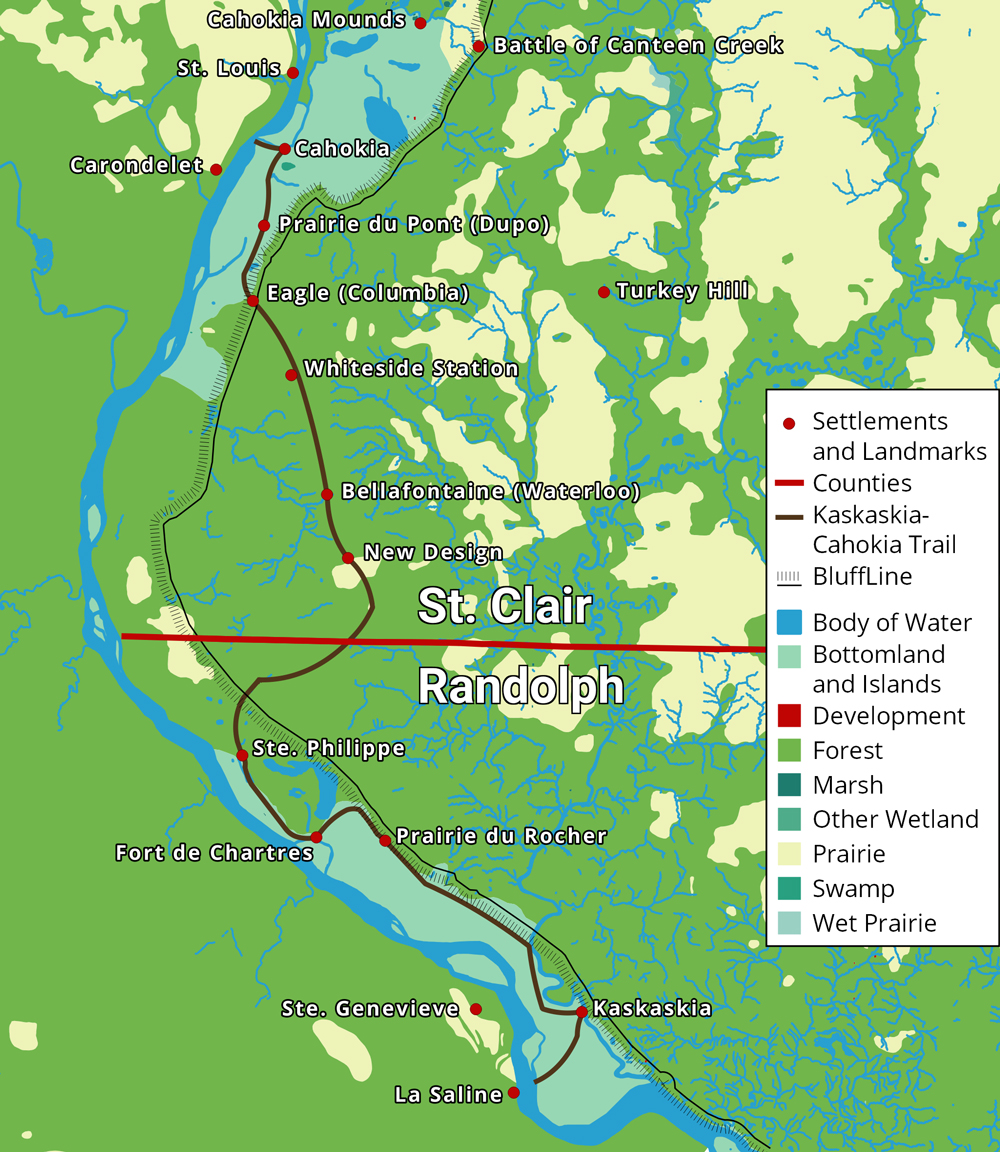

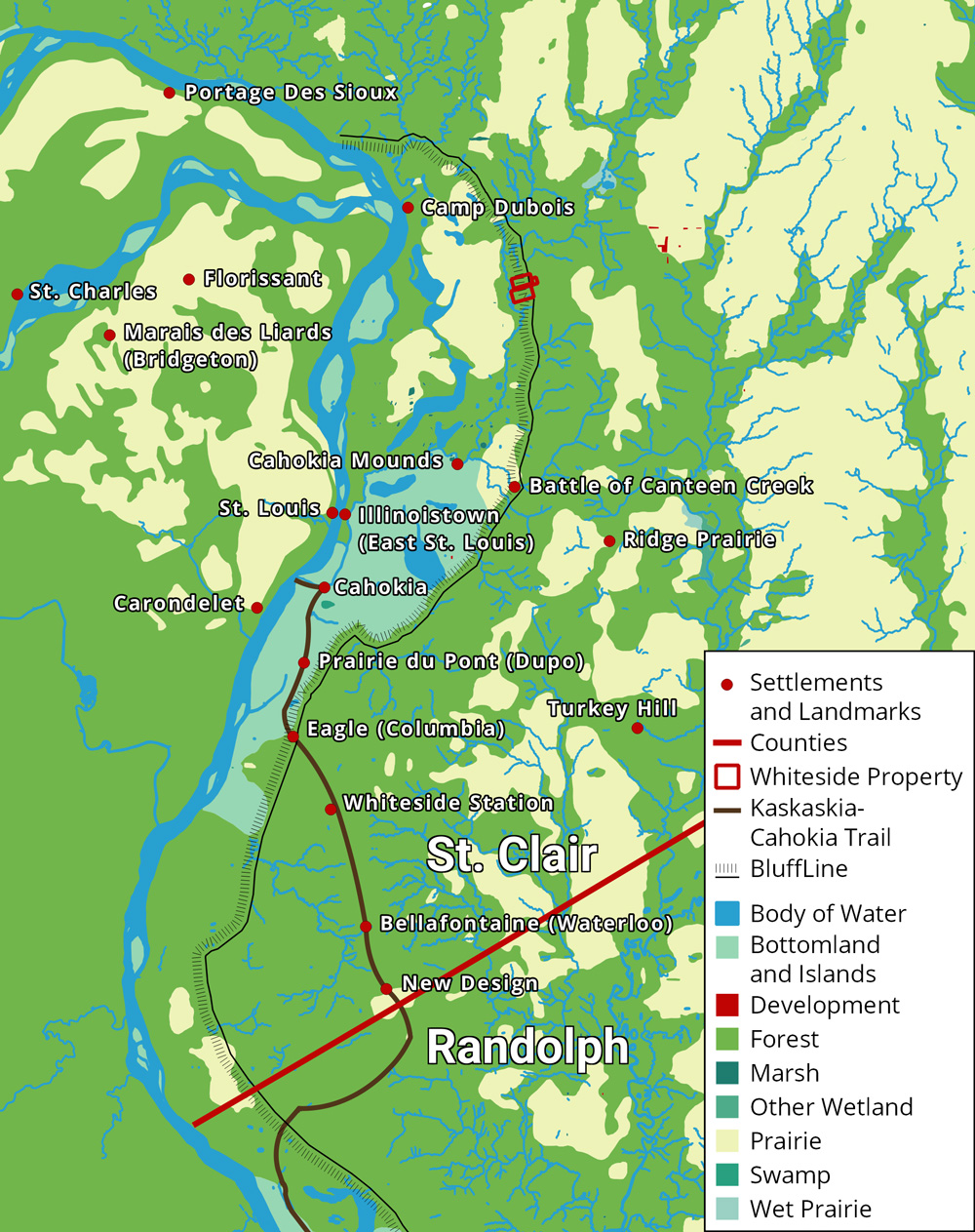

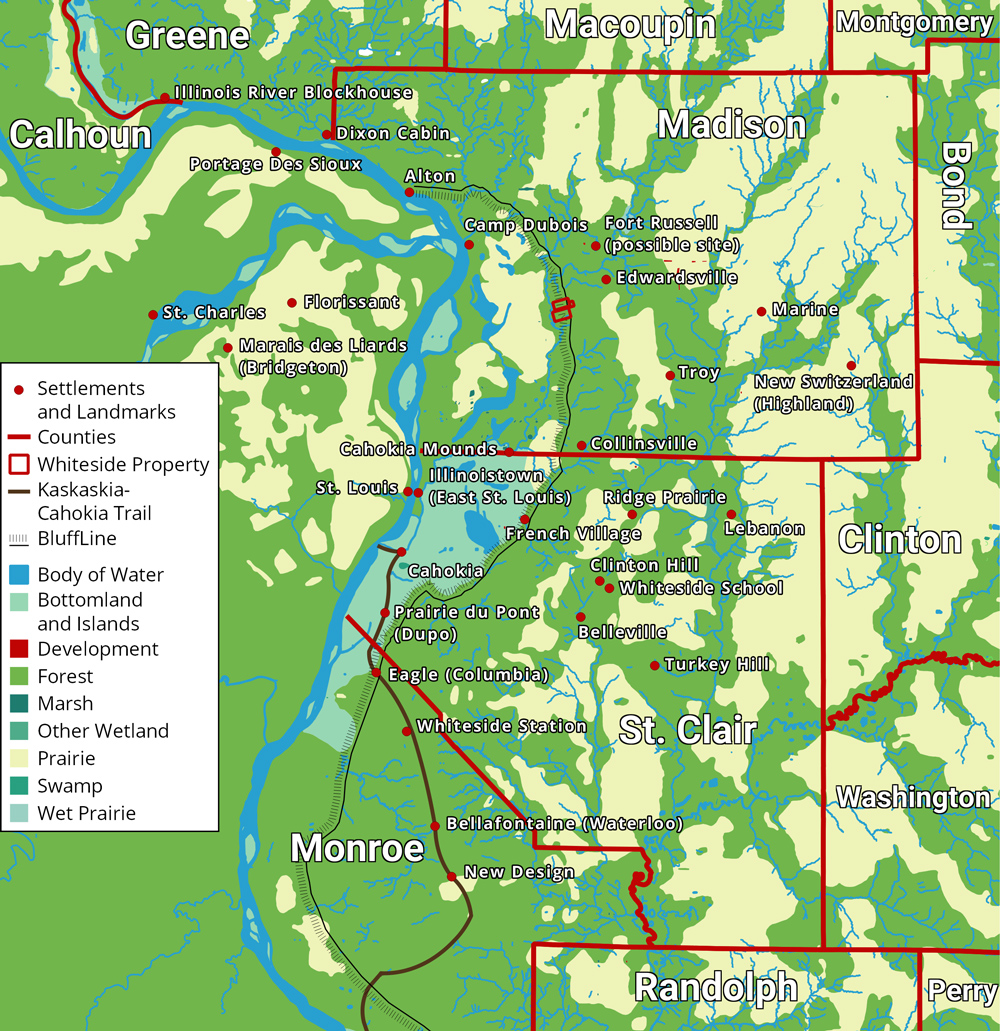

In 1778, those violent Anglo-Americans along the Ohio reached Illinois in George Rogers Clark’s famous Illinois Campaign, in which the Virginia militia officer captured British military installations in Illinois during the American Revolution.13 A number of veterans of Clark’s campaign either stayed in Illinois or returned later in life, bringing with them friends and family from places such as Virginia and Maryland. Bellefontaine and New Design were the first settlements Anglo-Americans established in 1779 and 1786 respectively; both located in the present-day Metro East of St. Louis.14 At this time, this region gained the name “American Bottom,” which encompasses the eastern floodplain of the Mississippi from modern-day Alton at the north to the Kaskaskia River at the south. It was likely named by these early Anglo-American settlers in the 1780s.15 The majority of them came from southern states such as Kentucky, Tennessee, the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland.16

Officially, Illinois had become part of the young United States, with all territory south of the Great Lakes and north of the Ohio River granted by Great Britain in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution.17 With its territory doubled in size, the United States had to determine how to incorporate the region into the new union; its future became a point of contention among the states. After Clark’s expedition, Virginia claimed the region as the Illinois County of Virginia. Other states held claim to what would become Illinois, including New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. States without western claims, such as Maryland, refused to ratify the Articles of Confederation unless those states ceded their claims, which they eventually did. The federal government decided to carve new states out of the territory, including provisions for this process in the Constitution in 1787. The Northwest Ordinance, passed the same year the constitution was crafted, organized the territory as the Northwest Territory.18

The Northwest Ordinance included provisions to placate French residents, including the maintenance of their land and property. They were exempted from Article 6, which specified: “there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory.” Yet despite this, many French migrated west to Spanish-led Louisiana as Anglo-Americans arrived. Many Anglo settlers had low opinions of the French, for they were Catholic, friendly with Indians, and foreign. In 1783 the French town of Kaskaskia had 155 French-speaking heads of families. By 1790, there were only 44.19

Yet however much they disliked the French, Anglo-Americans hated the Indians far more. Already tribes that had taken the place of the Illiniwek: the Kickapoo, Potawatomi, and others, harassed the French before Americans arrived.20 Kentucky settlers in particular brought with them experience in bloody warfare against Native Americans. For their part, Native Americans likely recognized the new settlers posed an even greater threat to their livelihood than the French. Indian groups frequently raided Anglo-American settlements, killed unsuspecting settlers, and stole horses. Whites led their own war parties against Indian villages, killing scores of Native Americans.21 Because of the danger, many Anglo-Americans built block houses or forts for defense from Native attack. One of these was Whiteside Station.22

The American military tried to quell Indian violence in the Northwest Territory. In 1790 General Josiah Harmer led an army of 1,500 into an ambush, with 180 killed. Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair led his own 3,000 man army in response, yet suffered even greater casualties. 630 died and 285 were wounded. Finally in 1794, General “Mad Anthony” Wayne won a decisive victory against Indians in the Battle of Fallen Timbers. This led to the 1795 Treaty of Greenville between American authorities and more than 1,000 Indian chiefs. Indians lost large chunks of Ohio, as well as the future locations of Peoria and Chicago. In return, Native American tribes received yearly payments in trade goods, making them further dependent on white authority. Native attacks became less frequent until the lead up to War of 1812. Though Indians largely remained in Illinois, the treaty set the stage for their removal.23

The Treaty of Greenville was joined by other critical treaties that year. The Jay Treaty forced remaining British troops out of forts in the Northwest Territory, while the Pinckney Treaty with Spain gave America navigation rights to the Mississippi and port access to New Orleans.24

Because of Indian warfare, difficulties in travel, and lack of public sales of land, the Anglo-American population received only occasional reinforcements from Kentucky and other southern states. By 1800, the total non-Indian population of Illinois was about 2,500, with lingering French making up about 1,500 of the population. The remaining 1,000 were Anglo-Americans, most all of them concentrated in the American Bottom. Four American settlements had sizable numbers. The largest was New Design with an unknown number of people, 250 in Eagle, 186 in Bellefontaine, and 90 in Fort Massac at the southern tip of Illinois. About 334 lived in various settlements, forts, and farms mostly in what would become Monroe County. The rest lived among the French in Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Prairie du Rocher, Peoria, and others.25 Another population lived in the American Bottom as well: enslaved African Americans. Though the northwest ordinance had explicitly banned slavery in the territory, many southerners brought their slaves with them to Illinois, either ignoring the law or “hiring” their slaves as “indentured servants” for decades. The French too were allowed to keep their slaves. With limited government authority and high demand for labor, slavery was allowed to persist in Illinois.26

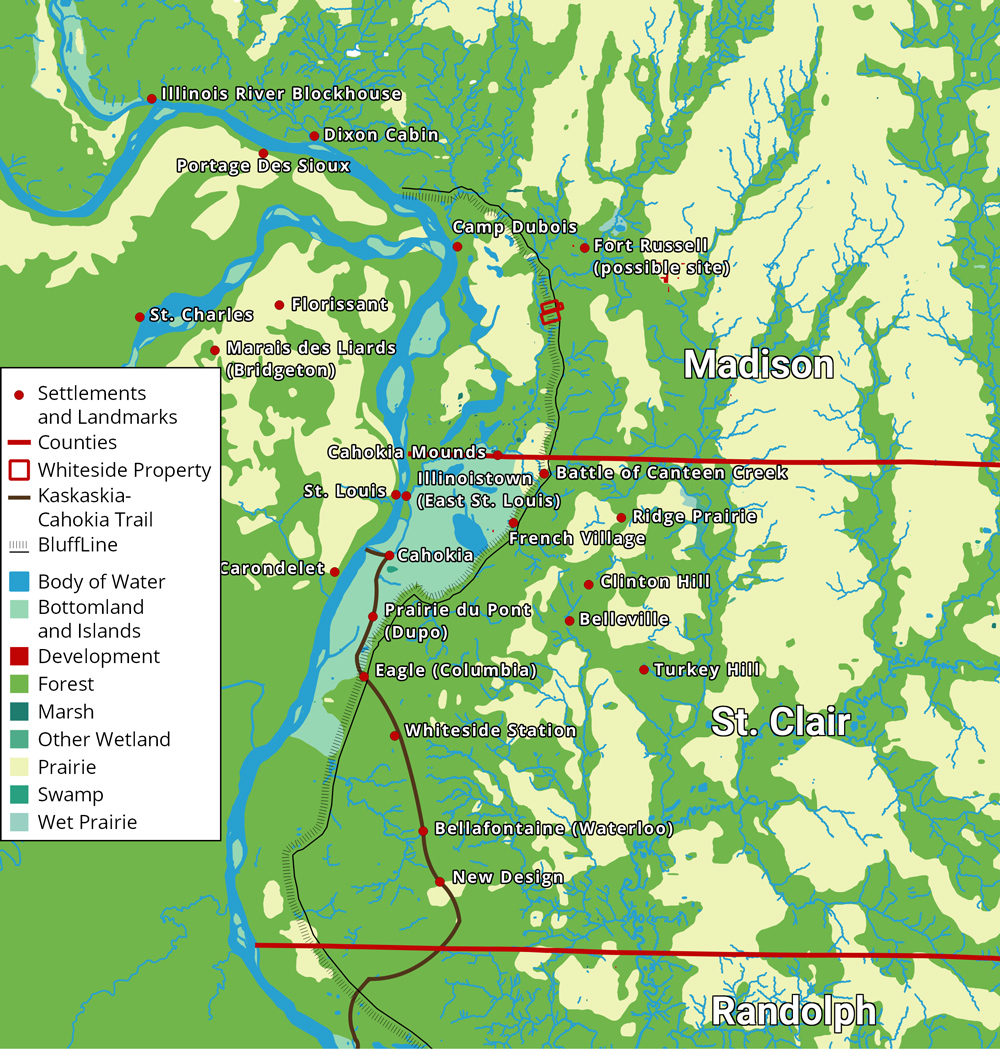

Now with access to the Mississippi River and threats from Indians lessened, Anglo-American settlements in the American Bottom expanded. Many migrated out from the forts and blockhouses to establish homesteads and farms. In 1802 two settlements were established to the north of previous settlements in what would become St. Clair and Madison Counties: Ridge Prairie and the Goshen Settlement.27

Further ties were also established with the growing port city of St. Louis. With the Mississippi now open to American traffic, Captain James Piggot established the first American ferry to St. Louis across the Mississippi in 1795. Economic and social ties cemented further with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, with St. Louis becoming an American city. The purchase also altered the American Bottom’s relative location, which became centrally located as an access point to the west.28 For instance, the Lewis and Clark expedition spent the winter of 1803 and 1804 training at Camp Dubois in what would become Madison County before beginning their expedition west on the Missouri River.29

The federal government acquired another territory in 1803: the Saline Creek salt springs near Shawneetown in eastern Illinois. Though not as grand as the Louisiana Territory, the salt works attracted further settlement into Illinois. Shawneetown acted as a gateway into the deeper territory of the American Bottom, with some settlers using it as a stop on the way to the American Bottom. In general, the American Bottom extended connections through St. Louis and Shawneetown. Farmers sold their surplus crops to markets through these connections, sending them by flatboat or keelboat up and down rivers. These markets were primitive however, with slow transportation and limited communication, so the profit from selling crops was fairly small.30

All of these factors led to a steady increase in Anglo-American population as more settlers arrived and children were born. It increased by a factor of 12 from about a thousand in 1800 to 12,282 in 1810.31 Because of the population increase and with Ohio close to statehood, the Northwest Territory was reorganized. The Indiana territory was created in 1800, including land that would become Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. Ohio itself became a state in 1803. Illinois was made its own territory in 1809.

The relative peace between Native Americans and Anglo-Americans started breaking down in 1809. Though the British had officially left the Northwest Territory, they still projected power from Canada through their Native American allies. The British hoped to maintain the lucrative fur trade, which American agriculture threatened. They were not interested in settling the territory themselves: they hoped to create an Indian buffer to halt American settlement and prevent Americans from gaining control of the Great Lakes. For their part, Indians recognized the threat Anglo-Americans posed to their sovereignty, so the alliance was formed.32

With British support and arms, Indians resumed frequent raids against Anglo-American settlements in southern Illinois, united behind the leadership of Tecumseh.33 Many settlers were killed.

Adding to the terror of the Anglo-Americans were two natural phenomena in 1811 seen as a harbinger of war: a comet and the largest earthquake in recorded history east of the Rocky Mountains: the New Madrid Earthquakes. Anglo-Americans felt as if nature itself was turning against them.

While unnerved by both natural and Native threats, Americans did not back down. In 1811 Congress authorized the creation of 10 companies of mounted Rangers to protect Anglo-American settlers. Four Ranger companies were charged to protect Illinois. William B. Whiteside was appointed captain of one of these companies, and his cousin, Samuel Whiteside, was appointed captain of another.34

Settlers meanwhile returned to blockhouses and forts for protection. Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards was an active participant in the war, leading troops into battle. In 1812 he ordered the construction of a fort in the Goshen settlement to serve as his headquarters, today in northwestern Edwardsville. Named Fort Russell, it was the strongest and most impressive fort in Illinois. Because the Goshen settlement was one of the most northern settlements, Fort Russel was the launching point of assaults into Indian and British territory in northern Illinois.35

In the east, the United States and Britain neared war for additional reasons. Chief among these was the rise of Napoleon and resulting conflicts between the American and British navies regarding trade and impressment of American sailors into the British navy. Thus Congress officially declared war on June 18, 1812.36

After two years of attacks and counterattacks, neither side gained a decisive victory in the west. Though Native American raids became less frequent, Anglo-Americans had failed to force Britain out of the northern Mississippi Valley. Their primary victory was the capture of territory around modern-day Peoria. However, Britain was weary of war with Napoleon, and Indian strength was diminished after American troops killed Tecumseh in 1813 and their alliance broke down. Raids had failed to dislodge Anglo-Americans from southern Illinois. Illinois was largely spared from the massacres and bloodshed in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Indiana. The most significant site of American bloodshed was Fort Dearborn at present-day Chicago, in which about 65 Americans in the fort were killed.37

The resulting peace treaty between Great Britain and the United States, the Treaty of Ghent, did not result in any territory changes. Britain kept Canada but gave up the prospect of an Indian barrier. Native Americans were left on their own to deal with Anglo-American settlement. Without British support, they never again were a serious threat to Anglo-American control of Illinois, even during their last ditch effort in the Black Hawk war 18 years later. A series of treaties between American authorities and Native American tribes during these 18 years gradually ceded away Indian sovereignty in Illinois. Many migrated west across the Mississippi or north to what would become Iowa.38

With fears of Indian attacks abated, Illinois began to rapidly expand after the War of 1812. The war kept the population around 12,000 in 1814, but by 1820 the state population increased about 450 percent, reaching 55,211. Veterans of the war in Illinois from other states returned with their families.39 As Reynolds, himself a veteran, wrote, “The soldiers from the adjacent States, as well as those from Illinois itself, saw the country and never rested in peace until they located themselves and families in it.”40 The federal government encouraged War of 1812 veterans to settle in Illinois, gifting 160 acres to settlers in western Illinois between the Illinois and Missouri Rivers, north of the American Bottom.41

Perhaps the most critical encouragement of Illinois settlement was the opening of public land sales in 1814. The first land office opened in Kaskaskia in 1804 but spent a decade sorting out disputed French land claims. Shawneetown opened the second land office in 1812. The third land office opened in 1816 in a new community in the Goshen settlement, Edwardsville, itself not officially incorporated until 1818. Before the public land sale, most settlers either owned French land claims or squatted, hoping their improvements would grand them eventual ownership. In numerous cases land offices approved squatters’ claims.42 With the public sale, prospective land owners could purchase as few as 80 acres for $2 an acre from the federal government. To ensure orderly and undisputed sales, surveyors were required to delineate boundaries. Under the northwest ordinance, the whole of the Northwest Territory was subdivided into ordered, square township and ranges.43

The prospect of cheap land and the possibility of independence were attractive to many hoping for a fresh start after the war. The war’s end also brought economic hardship throughout the nation, drawing many to a territory nearing statehood. This was particularly true for poor southerners during the rise of The Cotton Kingdom. Yeoman farmers could not compete with wealthy plantation owners, and many moved to free states and territories. Though Illinois had slavery in the early nineteenth century, unlike the antebellum south it was not endemic to the economy. Among those fleeing slavery was poor Kentucky farmer Thomas Lincoln who left with his family for Indiana and later to Illinois. These settlers’ opposition to slavery contributed to the peculiar institution’s death in Illinois.44

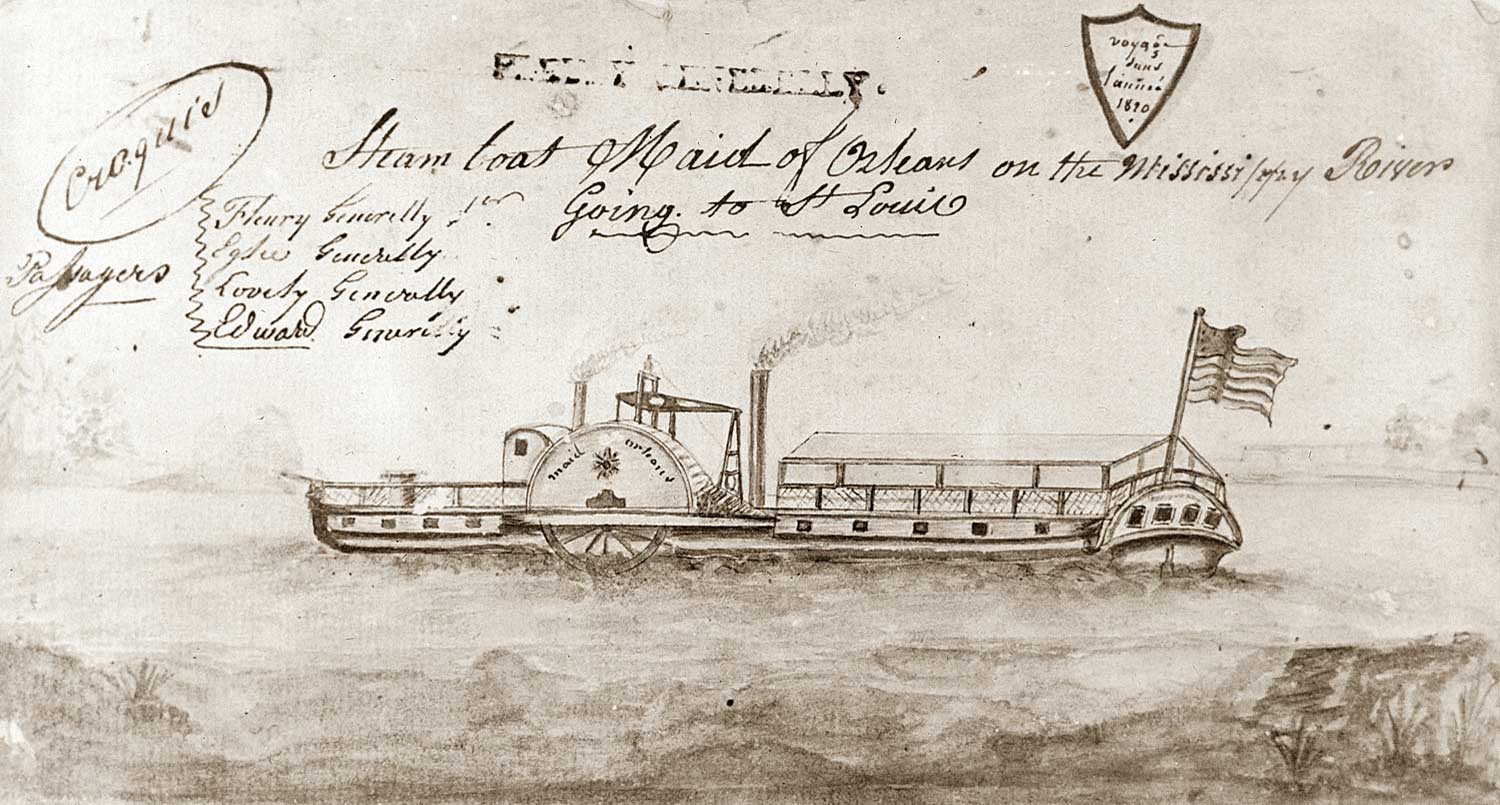

Most of the people of 1820 Illinois had a southern background, having settled the southern portion of the state. Though the population was concentrated in the American Bottom, other settlements were scattered throughout the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, and settlements were rapidly expanding inward and northward. Steamboats started coming up and down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, bringing not only more settlers, but trade goods and economic ties to the east.

All of this expansion led to calls for statehood, especially after Indiana became a state in 1816. However, the Northwest Ordinance required a population of 60,000, about twice what Illinois had. Congressional representative Nathanial Pope convinced Congress to lower the requirement to 40,000 as it had for Ohio. Most importantly, Pope arranged to have Illinois authorities do the official population count in 1818. To their chagrin, Illinois did not have 40,000 people in 1818, a more accurate estimate would be about 36,000. As a result, census counters creatively stretched their numbers using a variety of strategies – such as counting travelers as residents, deliberately overestimating the population of distant communities, and patriotic Illinoisans volunteering to be counted twice. This resulted in a count of 40,258, good enough for statehood.

Yet the population likely exceeded 40,000 the next year, reaching 55,211 in the 1820 federal census.45 The population continued to skyrocket through the 1820s and early 1830s thanks to both high birthrates and migrations to Illinois. The state census of 1825 showed 72,866 people,46 the 1830 federal census 157,445,47 and the 1835 state census 269,974.48 The rise in population came with increasing commercialization of the Illinois economy, as more and more steamboats shipped surplus crops and livestock throughout the country and brought eastern manufactured products to Illinois. The industrial revolution that began in England reached the St. Louis region upon the arrival of the first steamboat in 1817. 23 steamboats served the Mississippi in 1818, 89 in 1822, and 198 in 1831. Though road transportation was still expensive and unreliable in comparison, it too improved in the 1820s.49 Illinois even began to have railroads by the late 1830s.50

The most dramatic shift though was the rise of Chicago in the north. Illinois was not even meant to have access to Lake Michigan under the Northwest Ordinance: the northern border was drawn from the lake’s southern tip. Pope however lobbied upon statehood to have the northern border extended far enough north for Illinois to build a canal from the Illinois River to Lake Michigan. With the Erie Canal completed in 1825 that connected New York City to the Great Lakes, this canal would further connect eastern ports with the Mississippi River. Chicago was located at the center of this trading network and further cemented ties between St. Louis and the growing industry of the north.51 Construction began on the Illinois & Michigan Canal in 1836 and finished in 1848.52 With the rise of Chicago as one of the nation’s most massive metropolises, largely settled by Yankees and immigrants, southern influence on the state diminished.

The final bout of Indian violence in Illinois occurred in 1832, when a band of Sauks, Fox, and Kickapoos led by the Sauk leader Black Hawk crossed into Illinois from Iowa. Their intentions were likely peaceful, having suffered the previous winter from dwindling food supplies. Black Hawk and his followers hoped to farm corn in northern Illinois. They were not met peacefully. An armed militia went north to force them back to Iowa, including both William B. Whiteside and a young Abraham Lincoln. The future president did not see the resulting bloodshed. Some Indians not part of Black Hawk’s band took advantage of the fighting and attacked white civilians. After Anglo-Americans crushed any remaining Indian resistance, lingering Indians in northern Illinois ceded their last territory in Illinois. The final removal of Native Americans from Illinois in the 1830s was so sweeping, that today Illinois has no Indian reservations.52

All of these changes brought about the end of the frontier in Illinois.Though still largely rural with many areas still to be settled, by the 1830s Illinois had lost many of its frontier characteristics. With them went the lush vegetation and wildlife the first settlers saw in the 1780s.

To read how William Bolin Whiteside fits into this narrative, see Biography.

1. William R. Iseminger, “Culture and Environment in the American Bottom: The Rise and Fall of Cahokia Mounds,” in Common Fields: an environmental history of St. Louis, ed. Andrew Hurley. (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1997), 49.

2. James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 24 - 26.

3. Robert E. Warren, “Illinois Indians in the Illinois Country.” Illinois History Teacher 11:1 (2004), 19 - 28; Robert E. Warren, “Illinois Indians and French Colonists: Cultural Collaboration and Change.” Illinois History Teacher 11:1 (2004), 29 - 38.

4. Carl J. Ekberg, “Colonial Illinois: The Lost Colony.” Illinois History Teacher 12:2 (2005), 2 - 10.

6. “Voyageur Metis,” last modified 2012.

9. Jay Gitlin, The bourgeois frontier: French towns, French traders, and American expansion. (New Haven : Yale University Press, 2010), 29-30.

14. Douglas K. Meyer, Making the heartland quilt: a geographical history of settlement and migration in early-nineteenth-century Illinois (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 19 - 20.

16. The vast majority of Illinoisans were from the south in 1818. Davis, 159.

21. For example, the Whitesides participated in various raids on Indian groups, most notably in the Battle of Canteen Creek, in which they killed, at most, 60 Indians. See John Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois (Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1887), 188.

22. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 131.

27. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 314.

29. University of Nebraska Press / University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center, The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

36. U.S. Congress, “An Act Declaring War Between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Dependencies Thereof and the United States of America and Their Territories,” 1812.

40. Reynolds, The Pioneer History of Illinois, 410.

47. U.S. Census Bureau, “Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives: Illinois.”

51. Mark Stein, How the States Got Their Shapes. (New York: Smithsonian Books/Collins, 2008), 86 - 91.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.