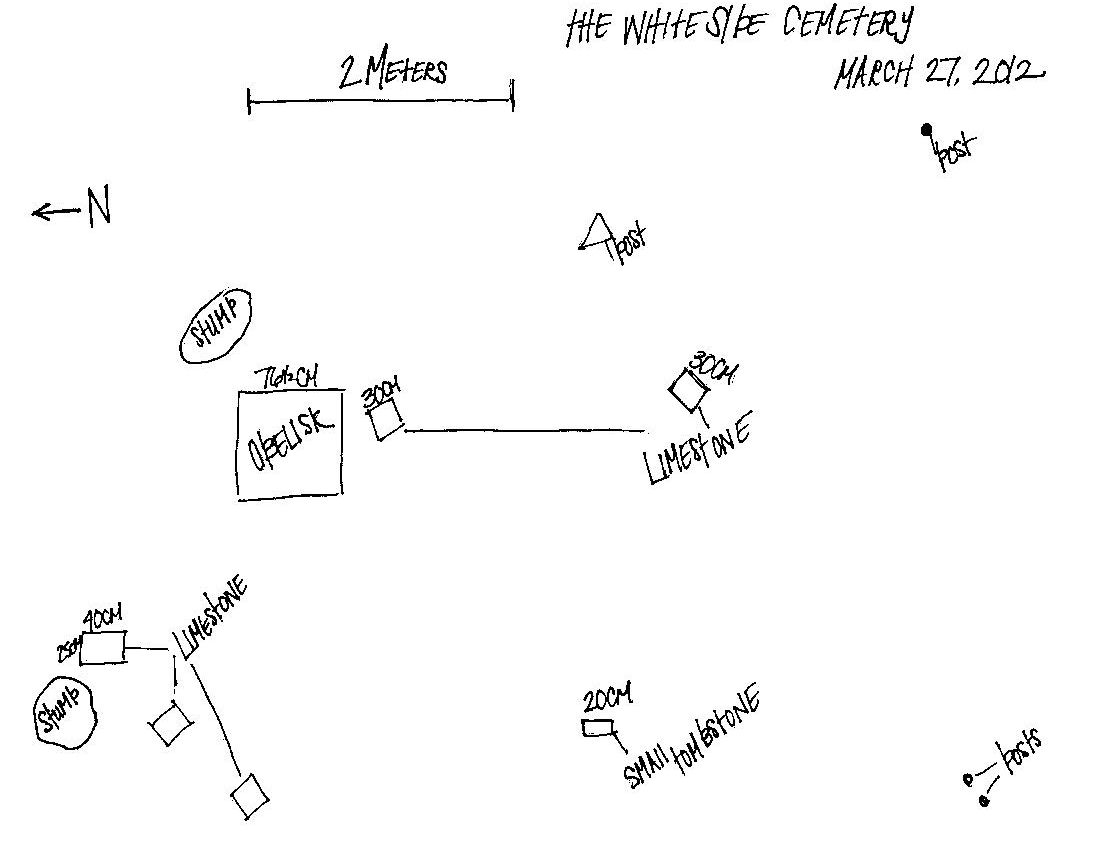

The study of Whiteside revolves around his gravesite. It is what began the SIUE history department's interest in Whiteside, it provides the primary evidence that Whiteside lived on the property, and serves as the last mark the Whitesides have left on this property. It is perhaps the most direct way to see into his psyche, which I analyzed in Statehood Ideology. Here, I will provide details on the gravesite and outline its history.

The cemetery consists of only one small tombstone and the large, white obelisk. The obelisk has four names on it, one for each face, each a member of William Bolin Whiteside's family. The small tombstone belongs to an 11-day-old child.

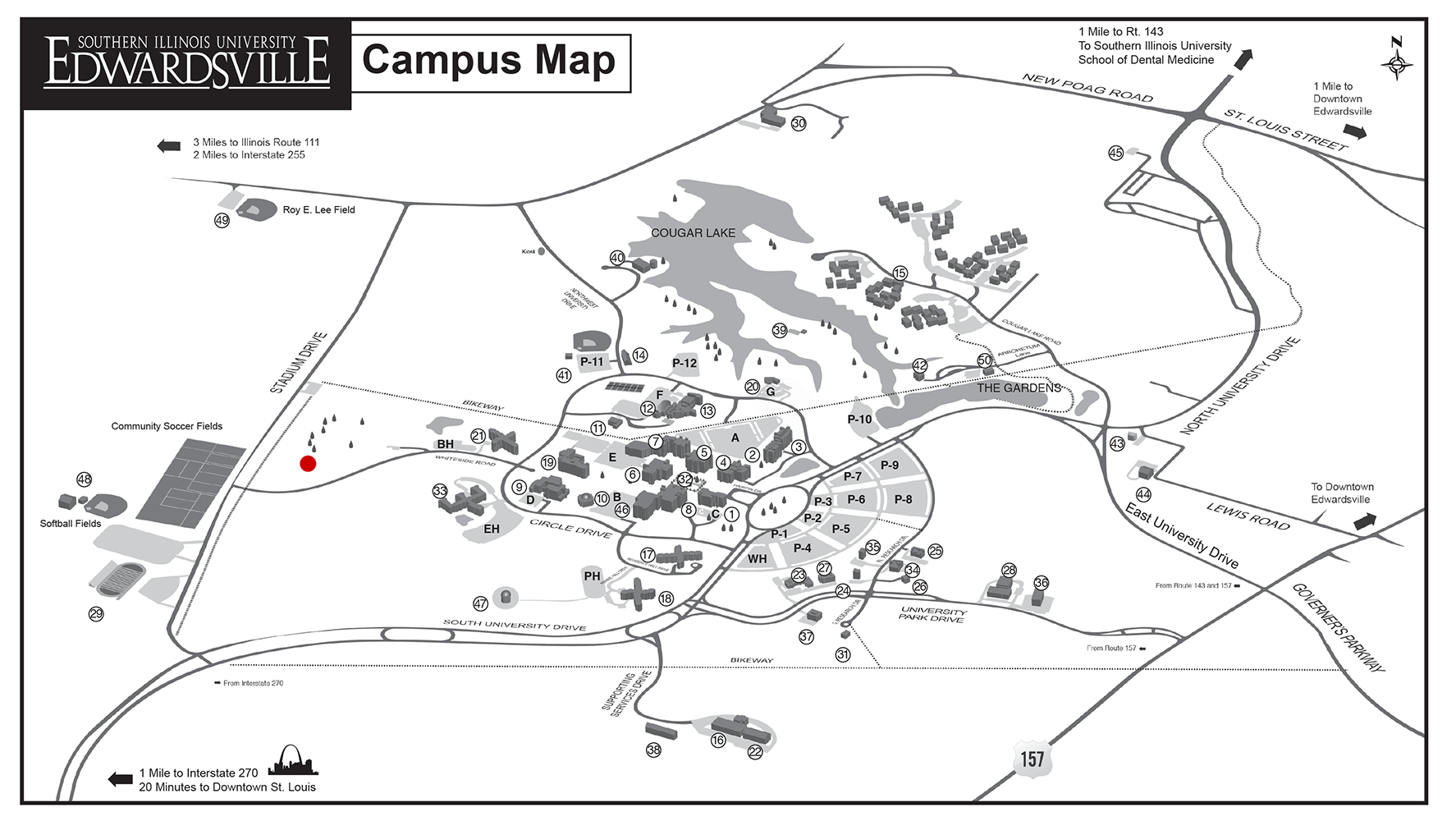

For a more precise location of the cemetery, see Maps.

The cemetery is located on the SIUE Nature Preserve, with the area south of Whiteside Road having returned to woods. A tree line has also returned about 100 feet north of the cemetery. SIUE has designated the hill as a prairie restoration site, with scheduled burns.2 As a result, when the prairie grasses get high it can be difficult to reach the cemetery to see who is buried there, though occasionally SIUE mows a path between the grass.

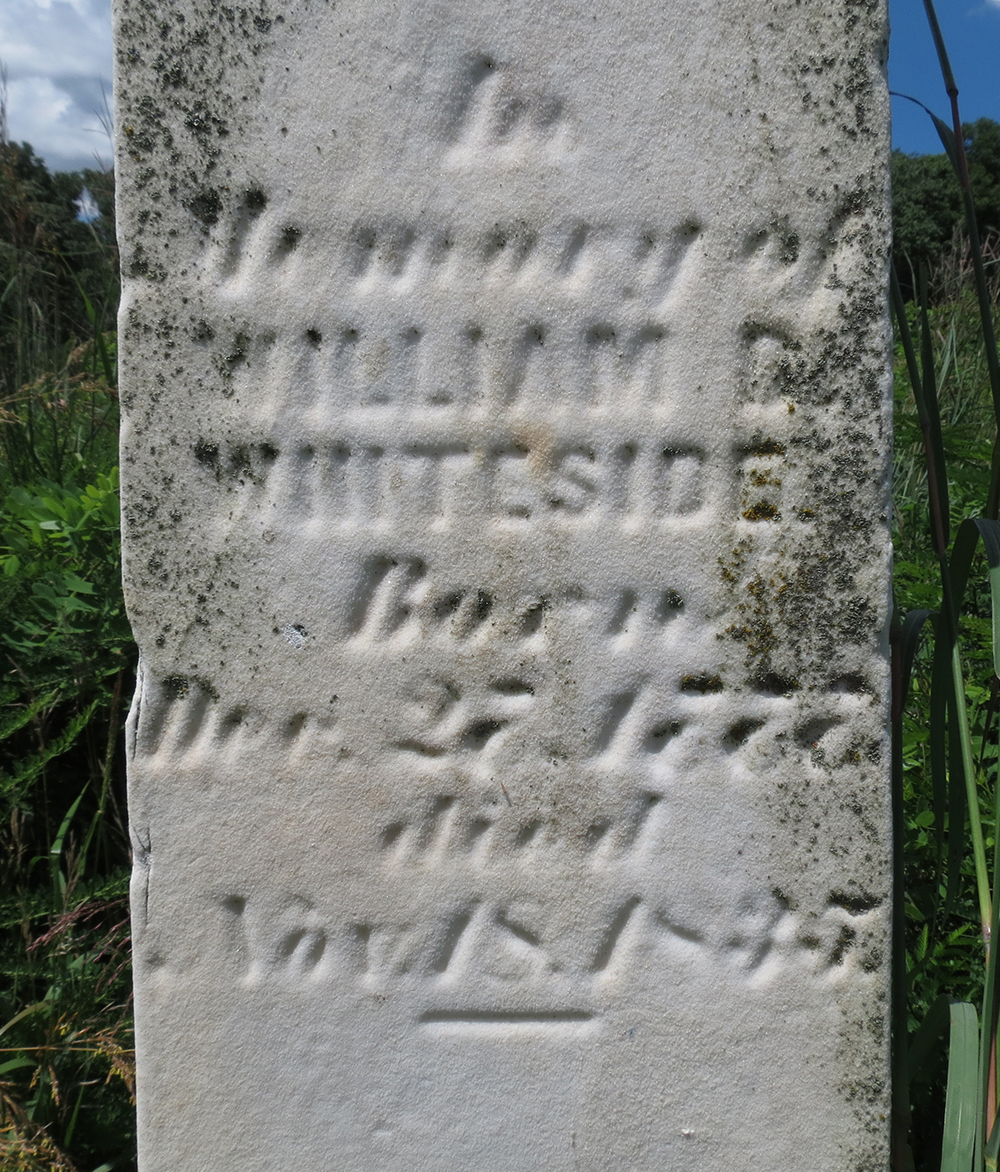

Here are the names on each face of the obelisk:

In

Memory of

WILLIAM B.

WHITESIDE

Born

Dec. 27, 1777

Died

Nov. 18, 1835.

Note: William B. Whiteside actually died November 18, 1833.3

In

Memory of

SARAH

SWIGGART

Born

June 16, 1799

Died

Dec. 6, 1835.

In

Memory of

SARAH

WHITESIDE

Born

Aug. 23, 1779

Died

July 30, 1833.

In Memory of

ELIZABETH A.

Wife of

Doctor John

Claypoole

Born

Aug. 7, 1806

Died

Sep. 23, 1867

Likely the most peculiar, and most tragic, part of the Whiteside cemetery is its second marker. It reads:

Infant son

Of

Wm M. & C.C.

REDDISH

Died

Feb. 8, 1866

aged

11 DAYS

William R. Whiteside has discovered the identity of the Reddish child, but the connection to the Whiteside family remains a mystery. The infant child, named Elvin, was one of twins born to William M. Reddish and Cornelia Caroline Ellis. The young couple married the year before, 1865, possibly because William Reddish's service in the Civil War had ended.4 The 1984 Stalker article states that the other twin, Elmer, died at birth in Granite City on January 28, 1866, which explains why he is buried in the Old Six Mile Odd Fellows Cemetery in Granite City.5

The author of the Stalker article further speculates that the Reddish family, with a sick infant, went to the Whitesides for medical attention from Dr. John Claypoole, Elizabeth Whiteside's husband.6 However, William R. Whiteside questions this interpretation. John Claypoole also died in 1866 in Fort Madison Iowa, where he and Elizabeth were living. It is also possible that Elizabeth had picked up medical knowledge from her husband and had returned to her childhood home by January 1866. Perhaps the Reddish couple sought her help.7 She was living in Edwardsville when she died a year later in 1867. Her obituary in the Madison Intelligencer indicates she might have taken in the sick infant:

Ever dispensing a generous hospitality, her home was particularly open to the needy and the orphan. Her offices of love and kindness to the sick within her reach, were constant and untiring; and her self-sacrifices in this regard without doubt shortened her life. Her benevolence was truly disinterested, and the aid and sympathy to the needy and suffering were without measure, and always rendered doubly valuable and endearing by the secret spirit in which they were extended.8

Another possibility not considered by William R. Whiteside is that Dr. Claypoole and Elizabeth were visiting the Whiteside farm in the winter of 1866, with Dr. Claypoole giving medical help to the Reddish child, only for the child to die and be buried next to Elizabeth's parents and sister. Dr. Claypoole then would have returned to Iowa to die later in the year of 1866.

In any case, the Reddish gravestone is deteriorating faster than the obelisk. In 1979 the curved top was still intact. By 1984, the top was "splintered and broken." 9Today there are remnants of two previous features of the gravesite. There are two stumps of honey locust trees and a few remnants of posts from a fence built in 1979.

The cemetery also has a number of stone blocks randomly distributed around the marked graves with an unknown origin. Each stone has an octagonal indentation in it. Possibly they are either the remnants of a fence older than the one built in 1979 or the fragments of other grave markers. There is additional evidence of more unmarked burials in the grave area from two recent geophysical surveys of the cemetery conducted by the anthropology department.

The first was a senior project in 2012 by anthropology student Amber Harper, who conducted a non-invasive survey using a magnetic gradiometer, which detects magnetic waves. Harper found the remnants from the 1979 fence and indications of a historic pathway to the cemetery and possible evidence of unmarked graves. Harper, however, encountered a great deal of magnetic noise. 10

The second survey was conducted in 2014 by students from the Arizona State University Field School. They conducted two surveys, another magnetometer survey and a resistivity survey. Surveyors once again found evidence for unmarked burials to the northwest of the obelisk. They also discovered remains of a barbed-wire fence on the surface, which may or may not be the same fence as one built in 1979.11 That fence was made of wooden posts tied together with wire,12 so the surveyors may have found that wire and assumed the fence was made of it. Or perhaps there was a barbed-wire fence built before 1979.

The survey also found that most of the surface stones correlated with metal beneath the surface, which could indicate rebar within the headstone foundations, the caskets were made of metal or had metal parts, or the Whitesides were buried with metal objects. Only one of the stones did not correlate with subsurface metal, likely indicating that the stone was moved. The report does not specify if that stone was one of the marked ones. Finally, the survey found possible evidence of landscape modification outside of the fenced area, such as "repeated plowing or mowing."13

Of the five known people buried at the Whiteside cemetery, the earliest death was Sarah Whiteside on July 30, 1833. William B. Whiteside died a few months later on November 18. Thus, 1833 seems the earliest possible time the obelisk was erected, but this is unlikely for two reasons.

More likely, the obelisk was erected shortly after Elizabeth Claypoole's death in 1867, possibly with her input before she died. Likely, it was erected by William T. Brown, the new landowner and husband of Mary E. Swaggert, Elizabeth's niece and William B. and Sarah Whiteside's granddaughter, along with any other remaining members of the Whiteside family. FN Before the obelisk, William and the two Sarahs might have had a makeshift grave that was deteriorating by 1867. Perhaps the carver of the obelisk mistook the "3" on Whiteside's previous grave for a "5," resulting in the wrong date, or perhaps the family misremembered the year he died.

We can only speculate on the state of the cemetery between Elizabeth's burial in 1867 and the opening of SIUE about a century later. During that time, the gravesite was on farm property with various owners, which you can see on the Maps page [work in progress]. People are usually respectful of gravesites, so if the hill was used for farming, they would have plowed around the cemetery, as indicated by the 2014 report. If that report was correct about a barbed-wire fence, at some point one of the owners must have put the fence around the cemetery.14 By 1979, there were fully grown locust trees in the cemetery, so they likely started growing before the opening of SIUE, either because farmers did not plow or weed in the cemetery, or they planted the trees themselves.

In the 1930s, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration was formed as part of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, which began to acquire aerial photographs of the United States. Madison County was first photographed in 1941, which gives clues about the state of the cemetery when it was on farmland. As seen in the photograph, the approximate location of the cemetery has a small grouping of trees, which is likely where the cemetery was located. This indicates that the locust trees were alive in 1941. Also around the trees is what appears to be a farm field, though it does not appear to be currently plowed.15

Additionally, at some point prior to 1967, the obelisk had fallen over, leaving enough time for brush to grow over it.

On November 25, 1975, groundbreaking began on Whiteside Road to connect Circle Drive and Bluff Road, now named Stadium Drive. This replaced the previous farm lane that went alongside the cemetery. The road was created by trainees learning road construction and was originally named the Whiteside Southwest Connector Training Roadway. The road took five years to complete, with an opening ceremony held June 26, 1980.19 The obelisk gained increased visibility with the new road.

The summer before the road was completed, 1979, 22 Youth Conservation Corps workers constructed a locust post fence around the cemetery as part of an eight-week summer conservation project. By 1979 there were two honey locust trees surrounding the two stones,20 possibly left to grow by farmers and later SIUE groundskeepers who avoided clearing and mowing around the graves. It's also possible someone planted them.

The locust trees were still there in 1984, but damage was visible to the gravesite, including the five-year-old fence. The Reddish grave's "once finely-curved top is now splintered and broken." The Stalker article further states:

Mother Nature and Father Time have worked together to rake and etch the smooth marble surface, chipping the edges of the tombstones and wearing away what's left of the corners...

Even the simple wooden fence built around the plot by the Youth Conservation Corp in 1979 is showing the effects of the elements which wear at it. The wire tying the thin posts together is almost rusted through, and the wood is starting to sag and crumble.

Every day the wind tears at it, shifts it slightly, working at its foundation. The stones tilt a little more, and every drop of rain tears at the stone, destroying the record the carved letters provide.21

William R. Whiteside returned to the cemetery on October 8, 2001. By then the fence was falling apart. The wires had rusted through, with some of the posts fallen over. Only the corner posts were left standing. The honey locust trees were still standing, but with yellow ribbons or straps on them. In 2003, Rick Pierce of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described the cemetery this way:

Weeds choke the tiny cemetery. A rusting metal folding chair lies folded nearby. Nylon straps with heavy metal hooks are tied around two locust trees — for what is unclear. Weathered fence posts still remain, flanking the tiny cemetery.22

My guess is that the nylon straps with hooks were used to stabilize the trees — to prevent them from falling onto the cemetery. They might have been dying. Both were gone by 2012 when I started attending SIUE, leaving only stumps behind.23

As for the fence, only one of the fence corners is left standing as of 2016, its rusty wire barely holding the two posts together. The rest have all fallen over. See the photos from 2016 in the gallery for images of the remains of the fence.

Pierce interviewed an SIUE spokesperson about how SIUE took care of the cemetery:

An SIUE spokesman said the weeds were trimmed inside the tiny cemetery occasionally, but he acknowledged that the university had not undertaken any restoration efforts. He said cutbacks had forced the university to scale back its mowing. However, workers still mow a strip up to the old cemetery from the appropriately named Whiteside road.24

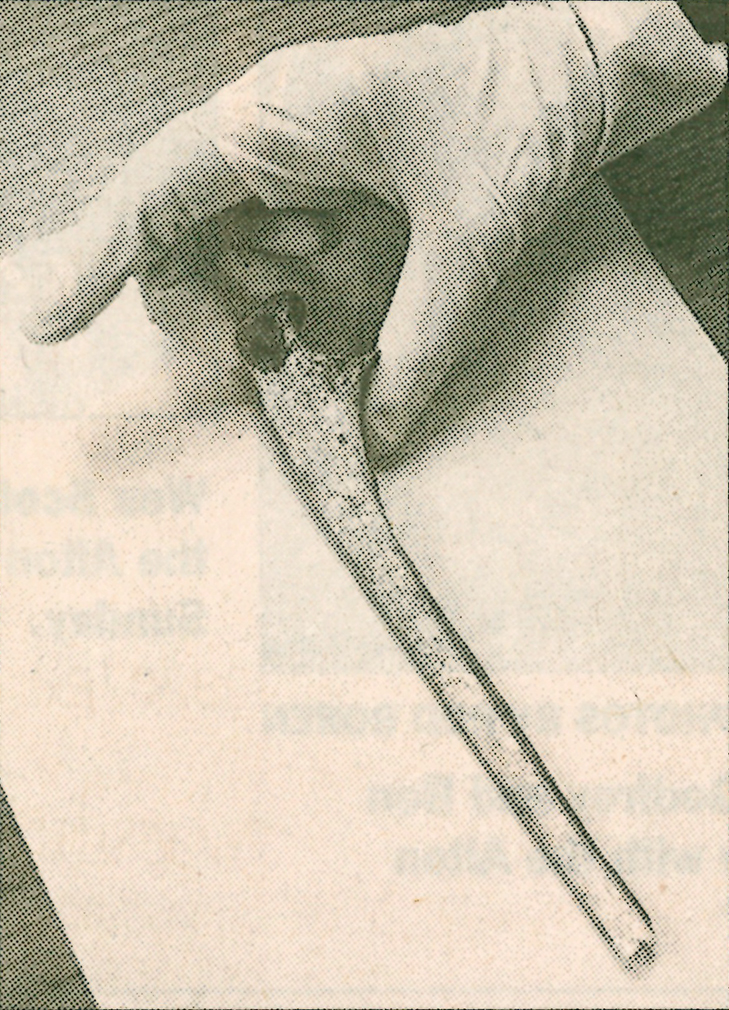

The cemetery made headlines in 2003 when a human bone was discovered on the grounds. Surveyor and local history enthusiast Jeff Pauk was visiting the Whiteside Cemetery in April 2003 when he found an arm bone underneath one of the locust trees. Pauk said he did not think that the bone was dug up; instead, his opinion was that the locust trees' roots pushed it up.25

After his discovery, Pauk contacted SIUE police, who then brought the bone to Madison County Coroner Steve Nonn. His office determined the seven inch long arm bone belonged to a small adult female who died more than a century before, though they could not determine the cause of death. The bone could have belonged to Sarah Whiteside or one of her two daughters, Sarah and Elizabeth, or even another unmarked burial, but investigators could not determine whose bone it was.26 All of the renewed interest in the cemetery is likely why there was a metal folding chair during Pierce's visit.

Though Pauk believed the bone should be reburied, the Illinois Human Skeletal Remains Protection Act mandated an attempt to find descendants of the Whitesides to determine what to do with the bone.27 Thus, Nonn shipped the bone to the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, which would then conduct the search.28

Unfortunately, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch did not follow up on this story, so it is unclear if the agency ever found descendants or what happened to the bone.

In recent years, the cemetery has gained a renewed interest from SIUE faculty. The anthropology department conducted two surveys in 2012 and 2014.29

In late 2012 and early 2013, history professor Jason Stacy became increasingly curious about the obelisk, walking out to it to see the name "Whiteside" carved on the side. He told fellow professors Robert Paulett and Jeffrey Manuel about the grave, and the three found the genealogy work of former SIUE professor William R. Whiteside in the Edwardsville Public Library. After some discussion, they decided to involve students in researching William B. Whiteside and form a research class taught by Dr. Paulett. Dr. Stacy first told me about this class in the spring of 2013, and I was enrolled in the class when Dr. Paulett first taught it in the spring 2014 semester.

1. I based this on Google Earth, which provides the elevation of any point on Earth. The elevation of the gravesite is about 158 meters, while the bottom land immediately west of the hill is at 140 meters above sea level. 18 meters is about 25 feet.

2. Tim Dickison, "SIUE now has protected nature preserve," This Week in CAS (Edwardsville, IL), January 24, 2011. SIUE personnel send occasional emails to the SIUE community warning of scheduled burns to maintain the prairie. I have received two emails regarding burns along Whiteside Road, one email on October, 16, 2013, and another November 19, 2013.

3. Probate Court of Madison County, Illinois, In the Matter of the Estate of William B. Whiteside, Deceased. Letters issued to Jacob Swiggert, 1834; Obituary of William B. Whiteside, Sangamo Journal, January 4, 1834, page 3 column 5.

4. William R. Whiteside, "The Whiteside Cemetery : Listing and Comments" (unpublished manuscript), part of genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

5. Janea Marie Little, "The Wind Never Seems to Stop Blowing Here," Madison County Genealogical Society Stalker 8, no. 3 (1988): 102; Whiteside, "Whiteside Cemetery." The Stalker article was originally in the September 1984 publication of the "J/Student" on page 16.

6. Ibid

7. William R. Whiteside, "Comments on Stalker Article" (unpublished manuscript), part of Whiteside genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

8. Obituary of Elizabeth Ann, Madison Intelligencer, October 3, 1867, page 2 column 3.

9. Little, "The Wind Never Seems to Stop Blowing Here," 102.

10. Amber Harper, "Surveying the Whiteside Cemetery Using Geophysical Remote Sensing Techniques" (senior project, SIUE, 2012).

11. Duncan P. McKinnon, Taylor H. Thornton, and Jason L. King, "Results from Geophysical Survey at Whiteside Cemetery on the campus of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville," (report, 2014).

12. Little, "The Wind Never Seems to Stop Blowing Here," 104.

13. McKinnon et al., "Results from Geophysical Survey."

14. Ibid.

15. Illinois Natural Resources Geospatial Data Clearinghouse and the Illinois State Geological Survey, "August 31, 1941 Madison County Aerial Photography," from Illinois Historical Aerial Photography 1937-1947, (object name 00sj02104; accessed January 8, 2016).

16. Stephen Kerber, "SIUE 50th Anniversary Historical Timeline," SIUE University Archives, 2007.

17. Charlie Skaer, "Small cemetery tells grave story," The Alestle (Edwardsville, IL), March 8, 1979.

18. John Costopoulos, "Graves tell Illinois history," The Alestle (Edwardsville, IL), April 28, 1972.

19. Kerber, "SIUE Historical Timeline."

20. Mary Brase, "Youth Corps learns old local lore," The Alestle (Edwardsville, IL), July 18, 1979.

21. Little, "The Wind Never Seems to Stop Blowing Here," 102 - 104.

22. Rick Pierce, "Neglected care raises more than questions at old cemetery," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 10, 2003.

23. Harper, "Surveying the Whiteside Cemetery."

24. Pierce, "Neglected care."

25. Ibid.

26. Rick Pierce, "Arm bone discovered at SIUE cemetery is sent to state historical agency," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 28, 2003.

27. Rick Pierce, "Human bone discovery will require search for Whiteside descendants," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10, 2003.

28. Rick Pierce, "Arm bone discovered at SIUE cemetery."

29. Harper, "Surveying the Whiteside Cemetery;" McKinnon et al., "Results from Geophysical Survey."

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.