Before you read this page, I recommend reading the general background of Frontier Illinois if you are not familiar with frontier Illinois history. This will give you a more broad history of the region that will help explain William B. Whiteside's life.

Knowledge of the Whitesides and William Bolin in particular comes from two primary sources.

William R. Whiteside is a former SIUE professor of special education, who taught from 1969 to 1993. He is not a direct descendent of William B. Whiteside’s particular branch of the Whiteside family, but people at SIUE would ask him if he knew anything about the Whitesides that were buried on campus. He took it upon himself to research the genealogy of not just William B. Whiteside, but the Whiteside family in general. He has been researching the Whitesides since at least the 1970s and continues to this day. This research is the basis for this page, and this project and website would not be possible without it.

The SIUE history department first obtained William R. Whiteside’s research from the Edwardsville Public library, where he donated copies of his research. He does not remember when he donated it; it was likely in the 80s or 90s. More recently, I obtained extensive copies of his research in early 2016.

The late Don Whiteside, however, is the most extensive researcher on the Whiteside family as a whole. He collected extensive information on the descendants of William and Elizabeth Whiteside, William B. Whiteside’s grandparents. Don wrote a manuscript on the Whitesides in 1969 titled The family of William (1710-1777) and Elizabeth (Stockton) Whiteside of Virginia and North Carolina, 1700 – 1969, and also wrote more than 80 papers on Whiteside family history.

Don’s work was used extensively by Carl R. Baldwin in Echoes of Their Voices, which is a history of the frontier American Bottom, particularly focused on Monroe County. Though perhaps filled with popular narrative history with artistic license rather than analysis, it is a more condensed version of Don Whiteside’s research, largely focused on the Whitesides in Illinois. Future researchers would be well served to look more closely at Don Whiteside’s work.

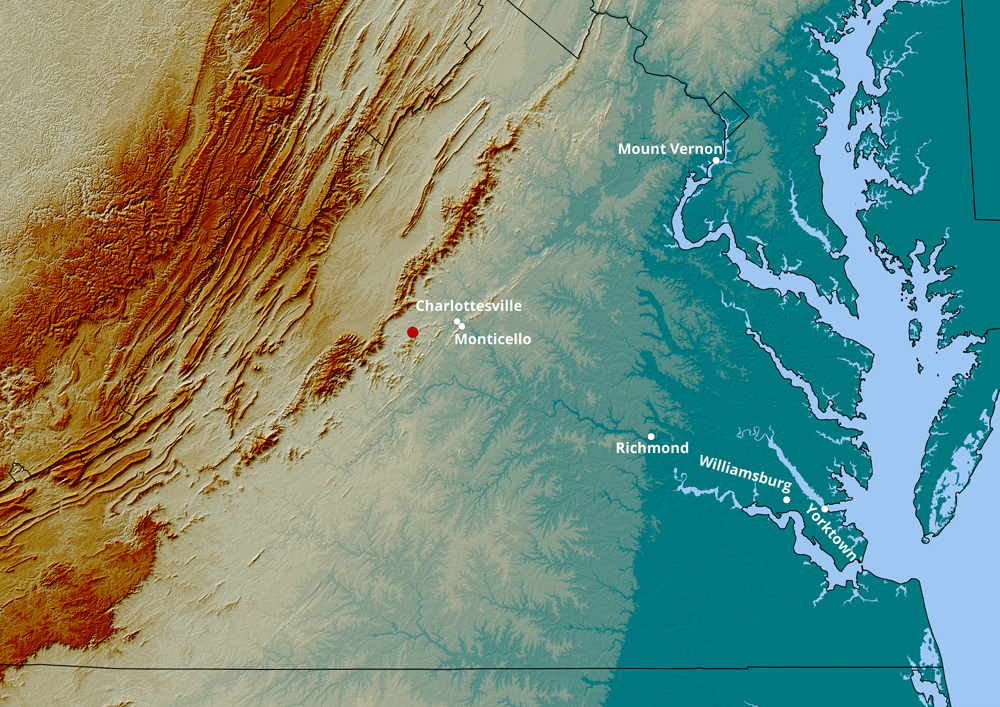

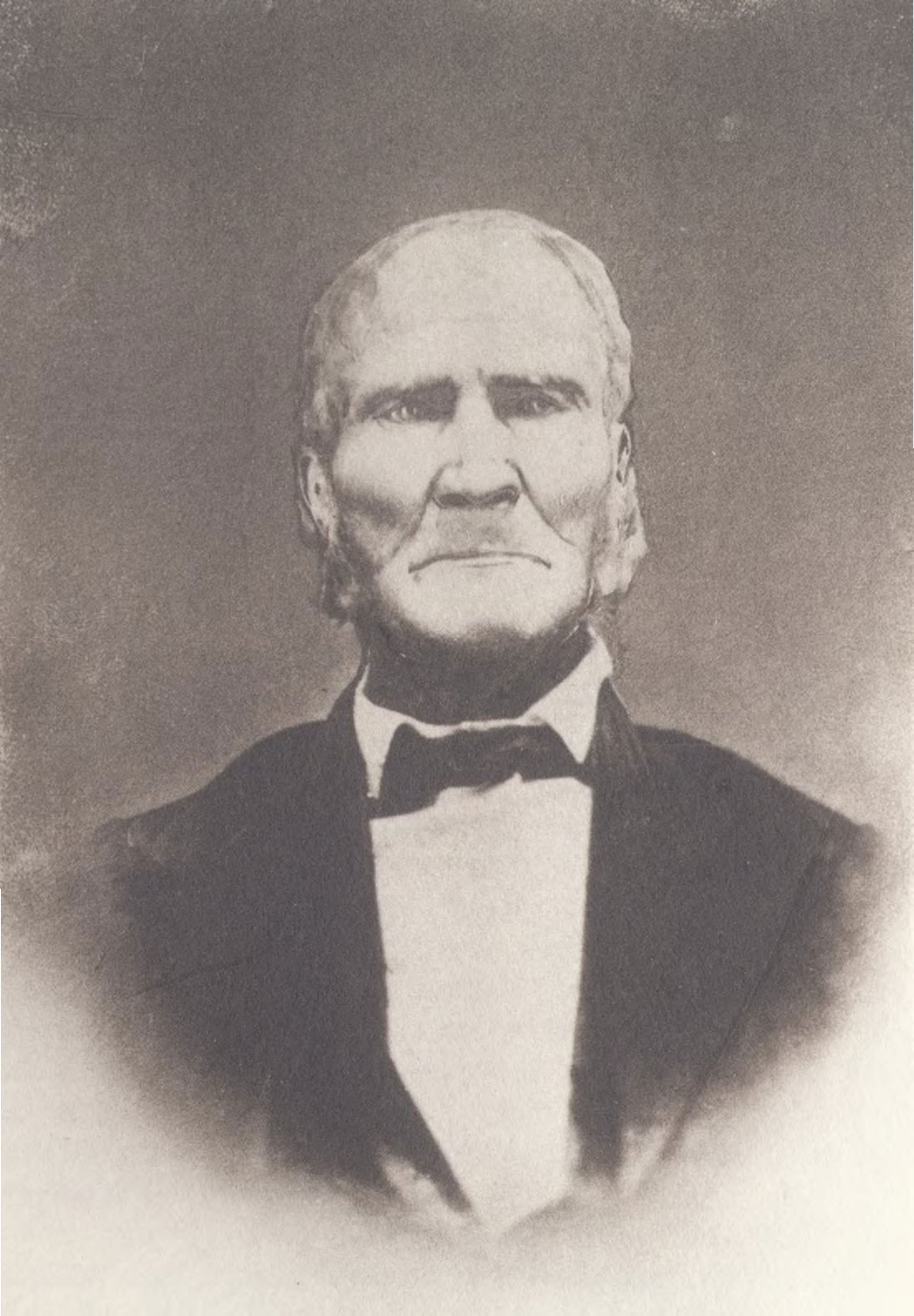

John Reynolds is one of the most prolific writers from frontier Illinois, who served as its fourth governor, one of the original justices of the Illinois Supreme Court, and a representative of Illinois in the U.S. House of Representatives. He wrote two books on frontier Illinois, a memoir titled My Own Times, Embracing also the History of My Life (1855), and a more general history, The Pioneer History of Illinois (1887). Before going off to college and becoming a politician, Reynolds’ life was relatively similar to William Bolin Whiteside’s, and I will be using his works to reconstruct Illinois settlers’ thoughts about landscape and nature. Like Whiteside, he was of Irish descent and followed a similar migration path to Illinois. He was born in Philadelphia in 1788, his family moved to Tennessee when he was six months old, and the Reynolds moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1800. Seven years later they moved to the Goshen Settlement, where Whiteside had been living for five years.1

Reynolds went on to serve under Captain William Bolin Whiteside in the War of 1812. His brother Robert also married Whiteside’s eldest daughter, Sarah. His two books are thus a useful source for biographical information on the Whitesides.

Most of what we know about William Bolin Whiteside is devoid of personality. I have only found two surviving letters written solely by his hand.2 Reynolds had this to say about the family as a whole:

They were warm-hearted, impulsive, and patriotic. Their friends were always right and their foes always wrong in their estimation. They were capable of entertaining strong and firm attachments and friendships. If a Whiteside took you by the hand, you had his heart. He would shed his blood freely for his country or for his friend.3

He also gave his opinion of William Bolin himself:

William B. Whiteside, the captain of the company of United States rangers in the war of 1812, was born in North Carolina, and when a lad, came with his father, Col. William Whiteside, to the country in 1793. He was raised on the frontiers and without much education, but possessed a strong and sprightly intellect and a benevolence of heart that was rarely equaled. All his talents and energies were exerted in the defence of his country. He was sheriff of Madison County for many years. At his residence in Madison County, he died some years since.4

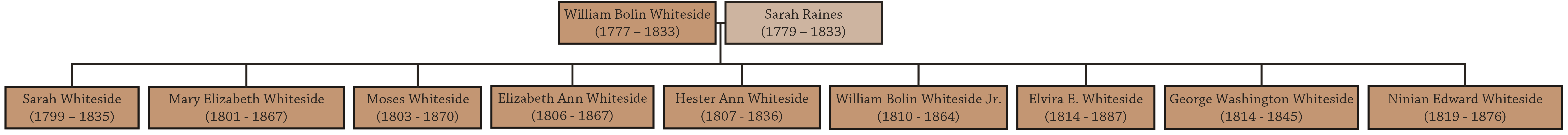

This section is for readers seeking a brief account of William Bolin’s life before I get into the details. He was an “Anglo-Irish” frontiersman born to a fighter in the Revolutionary War on December 24, 1777 in the backwoods of North Carolina. The large Whiteside family migrated to frontier Illinois in the early 1790s, and there his father became a leader in wars against the Indians. The family stayed in a fort named Whiteside’s Station in what would become Monroe County. William Bolin and some of his siblings and cousins joined in these wars once they were old enough. He later married Sarah Raines in the late 1790s and went on to have 9 children. In 1802 William Bolin, Sarah, and his brother Uel, along with other family members, moved to the new Goshen settlement near modern-day Edwardsville. William B. later served as captain of a company of mounted Rangers during the War of 1812, serving to defend settlements in the American Bottom from Indian attack. After the war, William served as sheriff of Madison County from 1818 to 1822 and continued to farm his property in the Goshen settlement. In 1831 he fought in the Black Hawk War to force remaining Native Americans out of Illinois. After returning home from the war, he and his wife both died in 1833, possibly from a cholera epidemic brought home by soldiers of the Black Hawk War.

To give a social background to Whiteside, I will first establish family history. The family name Whiteside originated in England. The earliest record is of a Robert Wyteside appearing in 1230 records in Warwickshire, England. Genealogist Don Whiteside believes most Whitesides throughout the British Isles are descended from Whitesides in the town of Poulton-le-Fylde in Lancashire County, England.5

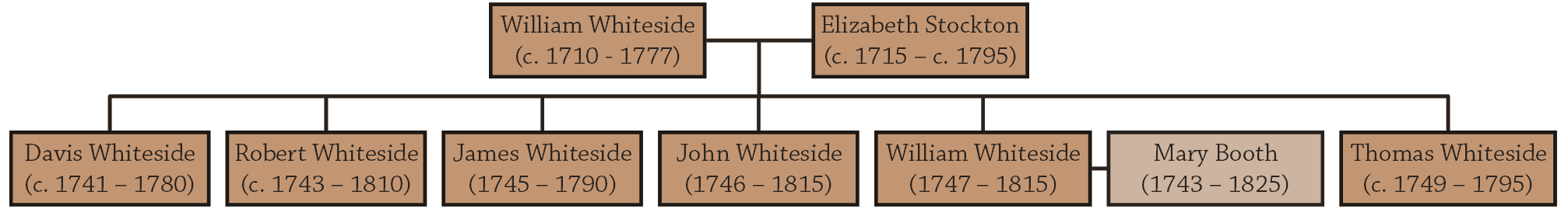

William Bolin’s grandfather, William Whiteside, was the patriarch of a large branch of the Whiteside family in America. He migrated from northern Ireland sometime between his birth in 1710 and his marriage in 1740. He eventually made his way to Goochland County, Virginia, where he married Elizabeth Stockton in 1740, herself the daughter of immigrants from northern Ireland.6 They were among a number of families from northern Ireland who migrated to the frontiers of the British colonies. These people are generally called Scotch-Irish, though the term is not entirely correct for the Whitesides. A more appropriate term for them might be “Anglo-Irish,” as the Whitesides originated in England, while the Scotch-Irish originate in Scotland. Reynolds himself said the Whitesides were “of Irish descent and inherited much of the Irish character.”7 They may have identified themselves as Scotch-Irish, as they followed their migration pattern. Regardless of the Whitesides’ technical ethnicity, Scotch-Irish history is relevant to their story.

The Whitesides themselves were not originally Scottish, but English. Based on a decline in Whiteside baptisms in Lancashire between 1650 and 1677, Don Whiteside believes a number of Whiteside families migrated to Ulster around this time.9 The ancestors of patriarch William Whiteside were probably among them, and he likely migrated to America for similar reasons as the Scots.

Most of the Ulster Scots were Presbyterian and migrated in groups organized by ministers. The first groups went to Boston, but violent intolerance from Puritanical New Englanders persuaded them and later arrivals to migrate to the more tolerant Pennsylvania, a sparser colony that needed settlers. They, along with Germans, came to gravitate towards the backwood frontiers for a variety of reasons, including the availability of cheap land that allowed groups to migrate together, as opposed to coastal regions already populated by occasionally hostile English settlers.10

The English colonists often grouped them with the Catholic Irish, which many resented, seeing themselves as "Scots" superior to the "Irish." Compromising, they became known in America as Scotch-Irish.11

The Scotch-Irish often made up the majority of the population on the inland frontier in many of the middle colonies: Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the Carolinas, eventually pushing westward into Kentucky and Tennessee,12 and thus ultimately southern Illinois. Many famous Scotch-Irish Americans came from this migration stream, such as Andrew Jackson, Davy Crockett, and Ulysses S. Grant.13 The Whitesides were also part of this migration stream, along with John Reynolds.

Patriarch William Whiteside and Elizabeth Stockton had thirteen children:

Davis, Robert, James, John, William (William B.'s father), Thomas, Margaret, Ann,

Elizabeth, Samuel, Adam, Francis, and Sarah, all born within about twenty years.14

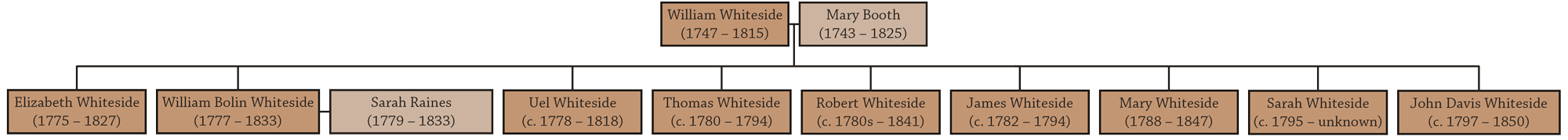

Due to space constraints, this family tree does not depict every child of William and Elizabeth.

In 1758, patriarch William served briefly in the French and Indian War. At some point afterwards, the Whitesides migrated from Virginia to then Tryon County, North Carolina, likely during the 1760s as the Whitesides had become prominent citizens of the county by the American Revolution. Baldwin speculates that they migrated due to soil depletion, as few farmers practiced crop rotation. Instead, they planted on the same fields year after year, draining the resources of the soil. This was especially a problem in Virginia with one of the most nutrient diminishing yet also one of the most profitable crops: tobacco. Land degradation required farmers to exploit new fields every few years, sometimes requiring migration elsewhere.15 Though there is no direct evidence, this is likely what pushed the Whitesides to North Carolina and later west to Kentucky and Illinois.

The Whitesides located their new plantation along the First Broad River in western North Carolina. According to Baldwin, Don Whiteside visited the site of the Whiteside plantation in the 20th century, and in Don’s opinion, it was one of the least attractive farm sites in the area. The access road was located between “pronounced ridges.” Yet Baldwin believes that patriarch William “had reached an age when he was content to plant fewer acres.” His offspring that were old enough had their own farms in fertile lowlands within a couple of miles of their father’s homestead, possibly including William Whiteside Jr., the future father of William Bolin.16 He married Mary Booth around 1774 as the American Revolution was simmering throughout the colonies.17

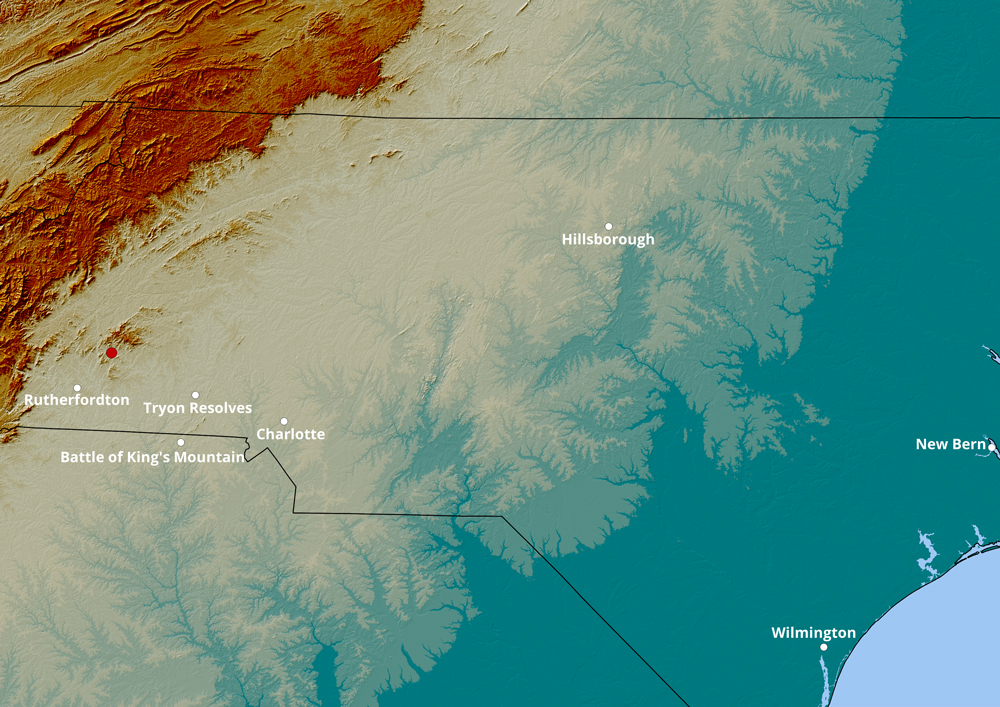

The county the Whitesides settled in, Tryon County, no longer exists. The county’s namesake was British governor of North Carolina William Tryon, who was despised by North Carolinian patriots. Thus the county was eliminated as North Carolina redrew its county boundaries in 1779, and the Whiteside plantation became part of Rutherford County. The former site of the plantation remains in Rutherford to this day.18

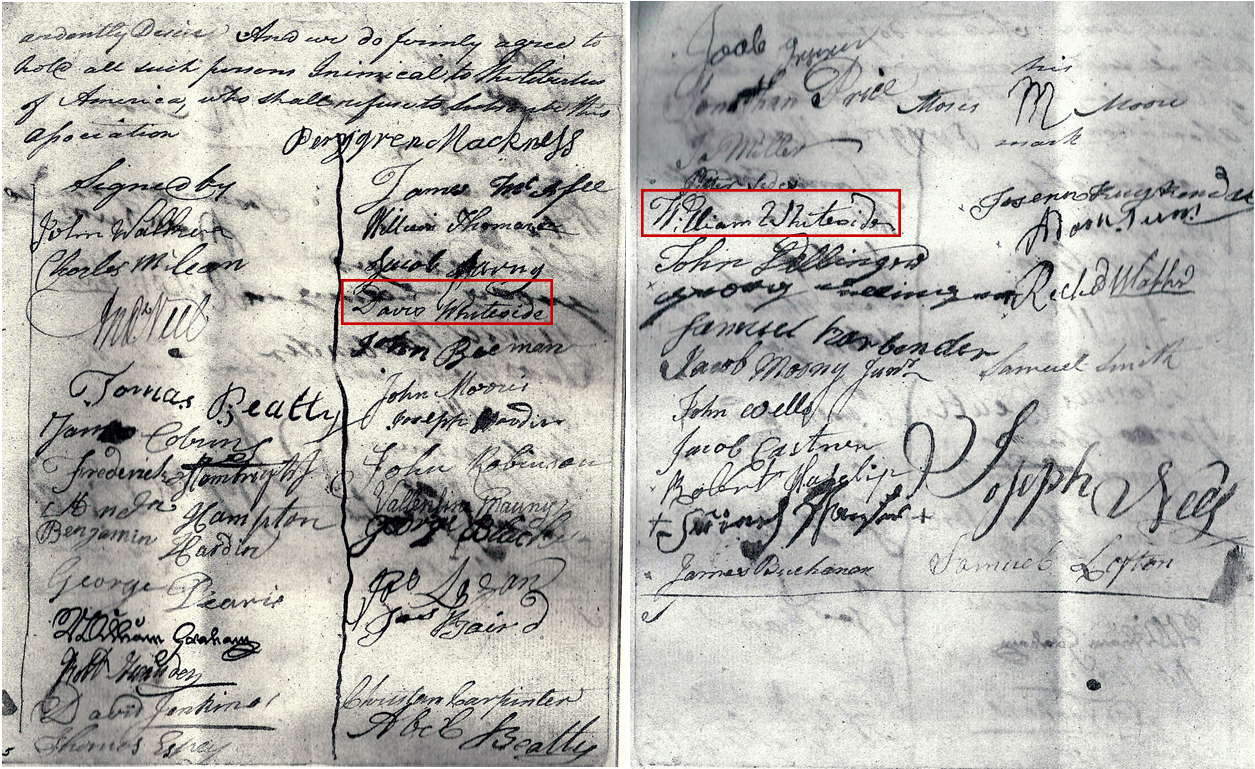

The Whitesides were among these patriots that favored American Independence. Both William B. Whiteside’s father and oldest uncle, Davis Whiteside, signed one of the earliest local declarations against the British government: the Tryon Resolves.19 Word of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts had reached North Carolina, and 49 citizens of Tryon issued the following declaration on August 14, 1775, 11 months before the Declaration of Independence:

The unprecedented, barbarous & bloody actions Committed by the British Troops on our American Brethren near Boston, on the 19th of April & 20th of May last together with the Hostile opperations [sic] & Traiterous [sic] Designs now Carrying on by the Tools of Ministerial Vengeance & Despotism for the Subjugating all British America, Sugest [sic] to us the painful Necessity of having recourse to Arms, for the preservation of those Rights & Liberties which the principles of our Constitution and the Laws of God Nature & nations have made it our Duty to Defend.—

We therefore the Subscribers freeholders & Inhabitants of Tryon County, do hereby faithfully unite Ourselves under the most Sacred ties of Religion Honor & love to Our Country, firmly to Resist force by force in defence [sic] of our Natural Freedom & Constitutional Rights against all Invasions, & at the same time do Solemnly Engage to take up Arms and Risque [sic] our lives and fortunes in Maintaining the Freedom of our Country whenever the Wisdom & Council of the Continental Congress or our provincial Convention shall Declare it necessary, & this Engagement we will Continue in & hold Sacred, till a Reconciliation shall take place between Great Britain & America on Constitutional principles, which we most ardently desire. And we do firmly agree to hold all such persons Inimical to the liberties of America, who shall refuse to Subscribe this Association.20

Many of the male Whitesides went on to fight in the American Revolution, including William Bolin’s father. Their patriarch William Whiteside only lived two years into the revolution, dying in 1777 of unknown causes. He was 69. More than likely he died of natural causes, for if he had died in the war it is probable the story would have survived to the present.

Yet younger Whitesides were starting to be born. William Jr. and Mary had their first child in 1775: Elizabeth.21 Two years later, their first son was born December 24, 1777 – almost exactly one year after Washington crossed the Delaware. They named their son after his father and grandfather: William Bolin Whiteside.22

Before intense warfare reached the southern colonies, many of the elder male Whitesides served in government. The oldest son Davis was appointed to the Committee of Safety which was responsible for securing and distributing arms. Davis later served as justice of the peace in Tryon County in 1778 and 1779 and became one of the first justices of the new Rutherford County in 1779. He was also Rutherford County’s first representative in the North Carolina House of Commons. His younger brother James became a frontier doctor, prospector, and also served as a justice of the peace in Rutherford County from 1781 to 1790. Thomas served in the North Carolina legislature, and was county trustee and treasurer from 1779 to 1782. After the war, he became the third Whiteside to serve as justice of the peace in Rutherford County.23

Yet not all was peaceful in North Carolina even early in the war. The British allied themselves with Native American war parties along the frontiers, arming them to harass American patriots. No doubt the Whitesides were part of the bloody frontier warfare that ensued. However, there is no direct evidence of this, except for a possible distant relative of theirs, George Russell, who was killed by Indians while on a bear hunt around 1781.24 This is likely when the Whitesides’ hatred for Indians was born, though perhaps it began even earlier when their patriarch fought in the French and Indian War. They would bring this fear of and aggression towards Indians with them to Illinois.

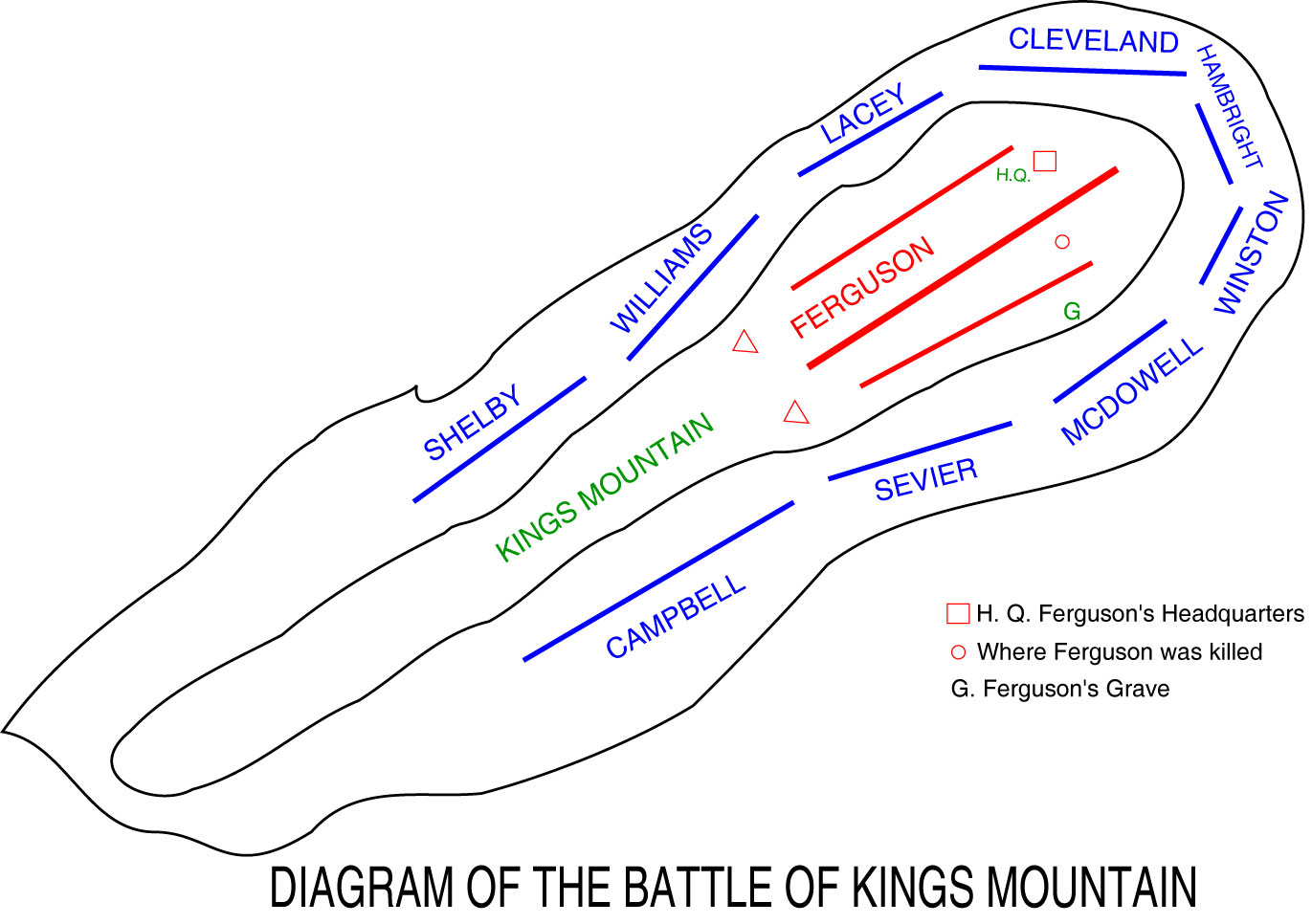

After failing to subdue American rebels in the middle and northern colonies, the British turned their focus to the southern colonies starting in 1778. Lord Charles Cornwallis carried out their new southern strategy: to recruit thousands of Loyalists to help subdue Patriots. The British won a number of victories over American Patriots early in their southern campaign, and in the summer of 1780, Cornwallis sent Major Patrick Ferguson into South Carolina to recruit Loyalist troops. In September, Cornwallis invaded North Carolina and ordered Ferguson to move north into western North Carolina and eventually join with Cornwallis’ army, putting him into the area of the Whitesides.25

Patriot militias rose up to oppose Ferguson. Minor skirmishes sparked between Ferguson’s Loyalists and pursuing Patriots. 900 Patriots eventually caught up to Ferguson’s army of 1,200 loyalists at a rocky hill just south of the border between North and South Carolina. Popular legend states that when Ferguson heard the rebels were coming, he said to his troops, “I am on Kings Mountain, I am king of this mountain and that God Almighty and all the Rebels of hell cannot drive me from it.” The Patriots decided otherwise and drove his forces off the mountain in about an hour on October 7, 1780. Ferguson died in the battle.26

Whiteside genealogists disagree on how many of the Whitesides participated in the Battle of King’s Mountain. Still, all nine Whiteside sons are recorded as having served in the Rutherford County militia except the youngest son, Francis, who was 22.27 Reynolds writes that at least William Bolin’s father fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain.28 The Rutherford County militia was among a number of local militias that fought at King’s Mountain, so it is likely that many if not all Whiteside brothers fought in the battle.29

The Battle of King’s Mountain demonstrates the brutality of frontier warfare. Though the Loyalists tried to surrender after Ferguson was shot from his horse and killed, the Patriots, remembering a previous battle at Waxhaw where the British did not allow them to surrender, continued firing at the Loyalists. In the end, 225 Loyalists died, 163 were wounded, and 716 taken prisoner. Only 28 Patriots were killed and 68 were wounded.30 Among the wounded was the eldest Whiteside, Davis. The nature of his injury has been lost, perhaps a bullet or bayonet wound. In any case, his brothers rushed him to Hillsboro, North Carolina for medical attention, but it was not enough. Davis died not long after reaching Hillsboro.31

The Whitesides’ fellow militiamen did not treat their prisoners well on the way to Hillsboro. They beat many of them brutally and hacked some of them with swords. A number of Loyalist prisoners did not make it to Hillsboro alive. The Patriots then appointed a jury to try the Loyalists. 36 were convicted of invading property, burning houses, and killing civilians. Nine were hanged.32 The brutality of this frontier warfare would travel with the Whitesides to Illinois.

Still, the service of the Whitesides at King’s Mountain helped bring the revolution to an end. Having lost Ferguson and his Loyalists, Cornwallis abandoned his invasion of North Carolina temporarily. As the first decisive American victory in the southern colonies, it would come to be seen as the turning point in the south. Patriots throughout the south stepped up their harassment of the British and Loyalists. Just a little more than a year later in late October 1781, the Americans and the French forced Cornwallis to surrender in Yorktown, Virginia. The world had turned upside down.33

William Whiteside Jr. and Mary continued to have children through the war. Uel was born shortly after William Bolin, followed by Thomas and Robert. James was born near the war’s conclusion. Mary was born in 1788, the last child born before the move to Illinois. William B. gained two more siblings in Illinois in the 1790s: Sarah and John Davis.34

Much of the Whiteside clan migrated to Illinois by way of Kentucky in the early 1790s. Likely they knew someone who had migrated to the American Bottom in the 1780s or word spread among backwoods men and women. This was very common among early settlers of the Northwest Territory. The first settlers would send word back to friends and family, who further spread word to others.35 The Whitesides may have known one of the soldiers who served under General Clark in Illinois.

Baldwin however writes that James Whiteside, William Bolin’s uncle, had visited the American Bottom in the 1770s. According to Baldwin, James was a self-taught doctor and prospector, eventually reaching the American Bottom in search of precious ore. James thus spread the word of the American Bottom to the rest of his family. However, Baldwin does not cite this claim, except for a reference to Cleveland’s Genealogy, which stated he was the first white American to visit Illinois. Baldwin even questions that claim.36 William R. Whiteside told me that the only reference that he has found to James visiting Illinois is in 1790 with other Whitesides. It is an issue worth looking into for future researchers, but I find the claim dubious at best.

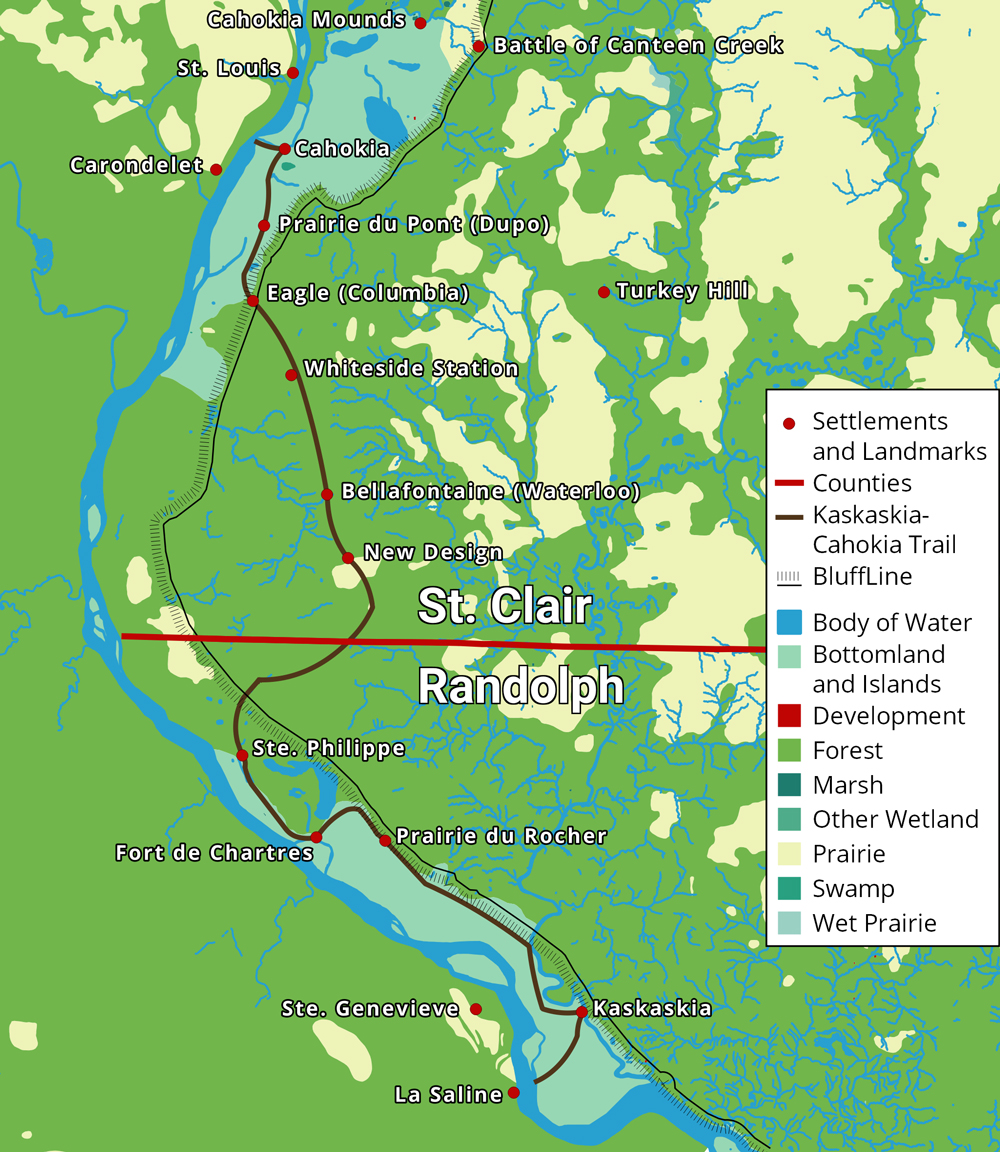

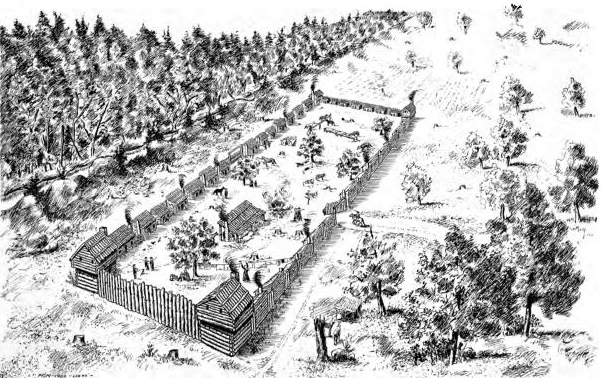

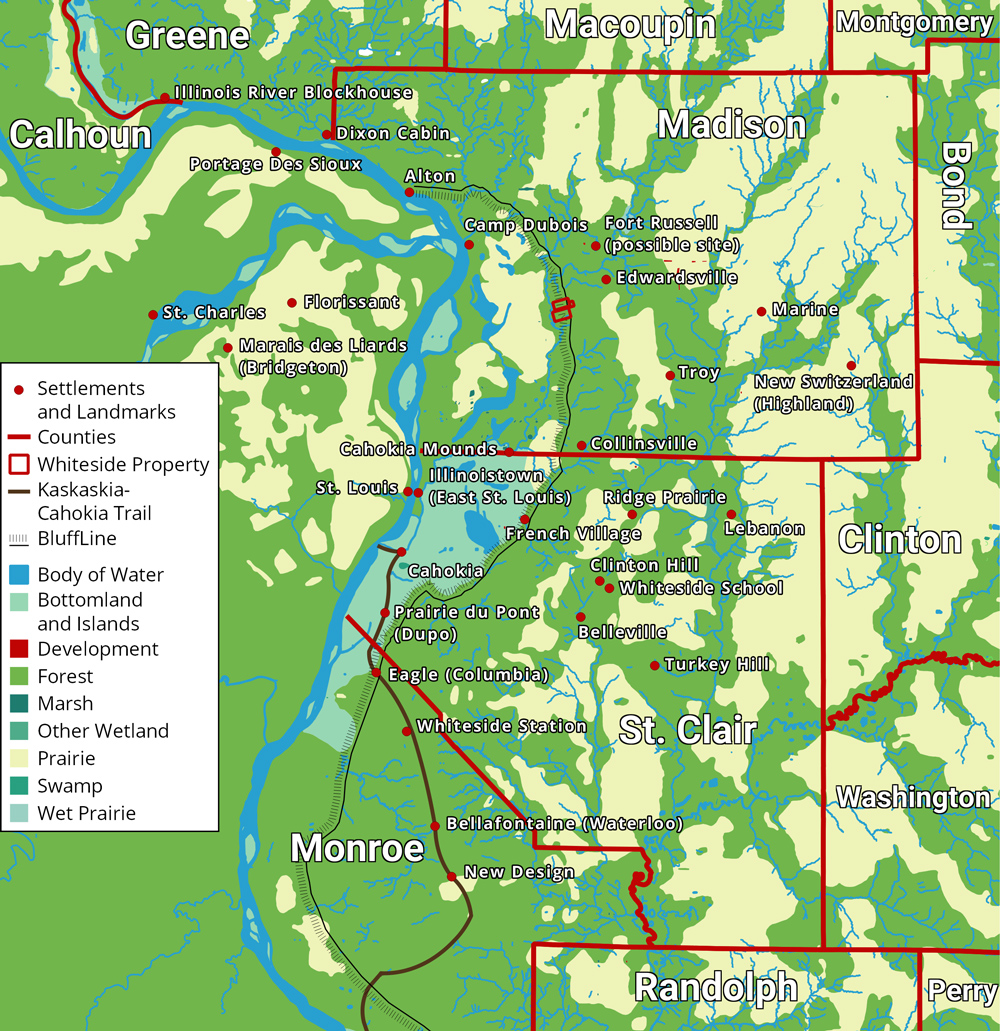

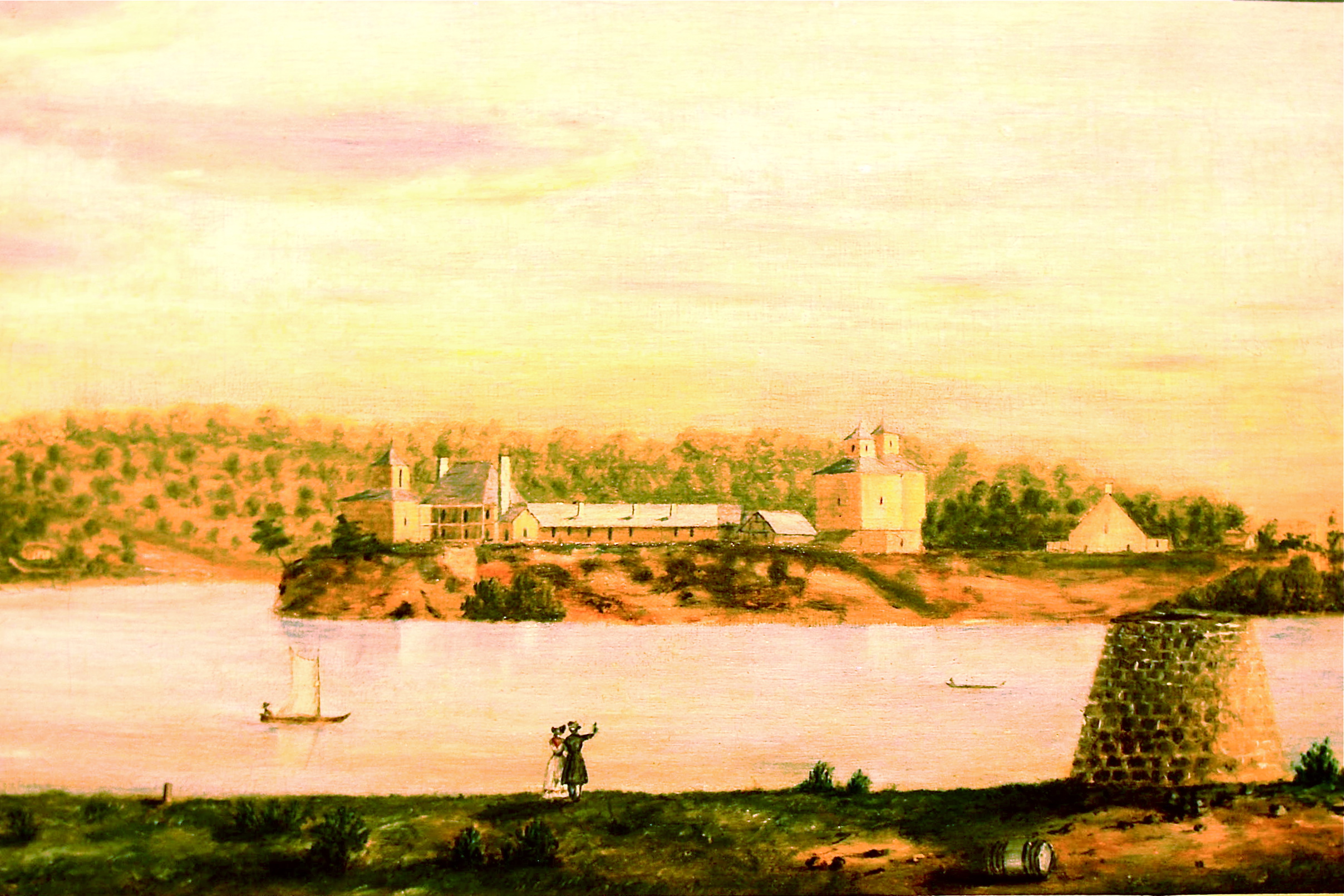

For whatever reason, at least four of the Whitesides were in Illinois by May of 1790: James, William (William Bolin’s father), John, and another William, likely James’ son and not William Bolin. They were living in Piggot’s Fort near modern-day Columbia in Monroe County, one of a number of forts or stations in the region.37 On May 23, 1790, 46 of the residents of Piggot’s fort issued a petition to Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, requesting legal right to the land they had built improvements on. This document is very revealing about settler ideas of land improvement, relationship to nature, and how Native Americans have affected both, which I analyze on Arrival Ideology.

For now, I will examine what it means for when the Whitesides moved to Illinois. They could not have been in Illinois for very long, as James had been justice of the peace until 1789, unless his two brothers had gone earlier. Both Baldwin and William R. Whiteside believe that they were visiting Illinois ahead of the rest of the Whitesides to scope out a place to settle. This petition was an attempt to gain land rights in the territory, and ended up going to both Arthur St. Clair and the U.S. Congress. Many of the signers of the document were granted their request, though Baldwin does not mention if the Whitesides were among them. Another signer of the document was a “Daniel Boon,” conventionally thought to be the son of the Daniel Boone.38

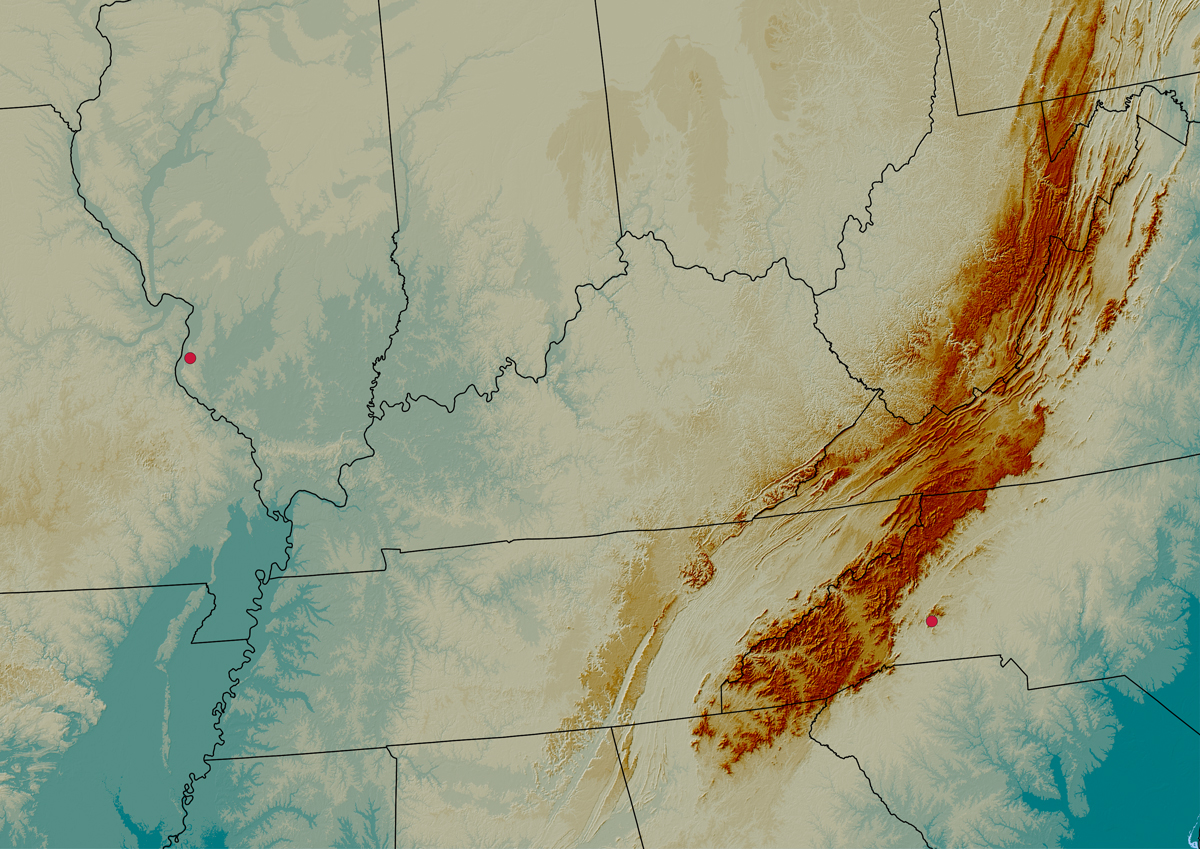

According to Don Whiteside, James Whiteside died in 1790, possibly on the hazardous way back to North Carolina.39 William Whiteside (father of William Bolin) and his brother Thomas Whiteside served as executors of James’ estate back in North Carolina. In either 1792 or 1793, a much larger group of Whitesides made the trek to Illinois, likely numbering in the dozens. All of William Bolin’s family went, even his younger sister, Mary, who was four. William Bolin himself was 14 and 15 during the journey. The going was difficult, requiring river forging and crossing the Appalachians into Kentucky. They then passed through Kentucky, and Baldwin believes they used flatboats to float down the Ohio River until they reached the Mississippi where Cairo is today. They then had to row the flatboats upstream on the Mississippi until they reached the American Bottom.40 Another possibility is they traveled overland after crossing the Ohio, as Reynolds did in 1800.

Reynolds arrived seven years after the Whitesides, but he likely heard about their reception afterwards or in general was familiar with how frontier folk reacted to the arrival of a clan of settlers. He writes:

In 1793, Illinois received a colony of the most numerous, daring, and enterprising inhabitants that had heretofore settled in it. The Whitesides and their extensive connections emigrated from Kentucky and settled in and around the New Design in this year…This large connection of citizens, being all patriotic, courageous, and determined to defend the country at the risk of their lives, was a great acquisition to Illinois, which was hailed by all as the harbinger of better times.41

Upon their arrival, the patriarchs of the Whitesides went to rebuilding an abandoned fort originally built by the Flannery family. They had abandoned the fort after one of them, James Flannery, was shot and scalped by attacking Indians in 1783. A decade later, the Whitesides gave new life to the fort, and it came to be known as Whiteside Station.42

According to Reynolds, William Bolin’s father had become the new patriarch of the Whiteside family in Illinois. He calls him, “the pioneer, Moses, that conducted [the Whitesides] thro [sic] the wilderness to Illinois, the ‘promised land.’”43 Reynolds further writes about how the new patriarch became involved in the Indian warfare:

William Whiteside, soon after he arrived in Illinois, became conspicuous and efficient as a leader in the Indian war. He was the captain of many parties that took signal vengeance on the savage foe for murders they committed on the women and children, as well as on the grown men. One trait of character bravery the Whiteside family possessed in an eminent degree, and the patriarch of whom I am speaking was as cool, firm, and decided a man as ever lived. Scarcely any of the family ever knew what fear was.44

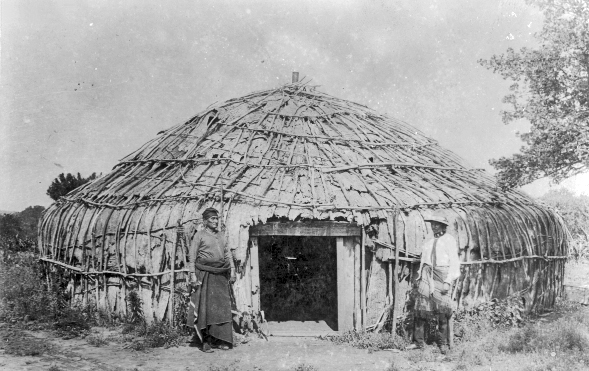

Shortly after the Whitesides arrived in 1793, a party of Kickapoo Indians raided the American Bottom and stole a “number of horses.” A group of eight frontiersmen was raised to pursue the Kickapoo on their ride north, captained by William Whiteside. His son William Bolin was still too young, but he was joined by his brother John Whiteside and John’s son, Samuel Whiteside. They were also joined by Samuel Judy, who would settle among the Whitesides in the Goshen settlement ten years later.45

Reynolds gives a dramatized account of the ensuing assault by the white attackers, one we must read with caution. Reynolds after all did not arrive in Illinois until 1800, and while he likely heard the story from those who participated in the attack, even that story was likely filled with added frontier drama. He describes them as not having time to even gather food for the raid, only bringing “their guns, ammunition, and bravery.” They were heading into “a country where hundreds of the enemy could be called forth in a few hours” with only eight brave pioneers with an “almost forlorn hope.”46

Yet let us not forget the original cause of the whites’ raid: the theft of horses. More than likely there were far fewer Indians behind the theft than Reynolds describes. Though horses were valuable, it seems unlikely that they would risk their lives so carelessly unless it was a matter of rescuing white captives. It was not just the horses that the whites were hoping to recover; far more important was white honor. By responding to the Kickapoo raid, they intended to send a message that Indian attacks would not go unanswered.

William Whiteside and his party caught up to the Kickapoo on Shoal Creek. The ensuing battle is further dramatized by Reynolds. They first found three of the horses grazing and untended by the Kickapoo. They recaptured these horses and proceeded to attack the Indian camp. One of them killed the chief’s son, which Reynolds couches in passive voice, “the son of the chief, old Pecon, was killed,” diminishing the fact that one of the whites killed him. In Reynolds’ account, the Indians quickly and cowardly ran off, leaving behind their guns, making them look like dishonorable fools. Chief Pecon had assumed that there were far more whites than eight and surrendered his gun to William Whiteside. Yet Pecon quickly realized there were only eight of them, and tried to grab his gun back from Whiteside. They struggled for a moment, but “Whiteside retained the gun in triumph and the Indian, altho [sic] a brave man, was forced to acknowledge the superiority of the white man.” To further highlight white supremacy, Reynolds recounts that Whiteside spared Pecon’s life because it would be dishonorable to kill an unarmed man.47

It is impossible to know for sure what actually happened in the fight, given the racist overtones of Reynolds’ account. Certainly all of the whites survived. It seems less likely that the episode with the gun actually happened or that the Indians gave up so easily. We must too remember that, in this whole episode, the only person to die was Pecon’s son at the hands of one of the whites.

Whiteside’s party quickly returned to Whiteside’s Station. The next year, 1794, Pecon and a group of Kickapoo made their way to Whiteside Station. 14-year-old Thomas, William Bolin’s younger brother, was playing outside the fort. Pecon tomahawked Thomas to avenge the death of his son. Reynolds writes, “There is no passion in the breast of a savage so strong as that of revenge.”48 Baldwin further states that the elder Thomas Whiteside, William Bolin’s uncle, went outside to fight the Kickapoo, along with Samuel Whiteside, but both were wounded. The elder Thomas Whiteside died in 1795, possibly from the wounds he suffered the year before.49

The elder William Whiteside had the chance to avenge the death of his son the next year, 1795. That late summer or fall, a Cahokia Frenchman informed Whiteside of an Osage encampment to the north, near modern-day Caseyville. Though the French were previously allied with Indian groups, those that remained in Illinois were generally less friendly to French settlers. Reynolds speculates that this Frenchman anticipated an Indian attack on himself, either to steal horses or kill him. William sprung at the chance to attack.50 Word of the Treaty of Greenville that brought a truce between Indians and Anglo-Americans had likely not yet reached the American Bottom. Even if it had, that may not have stopped William Whiteside after losing his son, even though it was a different tribe.51 He raised a larger group of men than before, including two of his children: William Bolin and Uel. Samuel Whiteside also joined them, as well as his brother William Lot Whiteside. Samuel Judy joined the raid as well. In total, 14 men participated.52

The assault became known as the Battle of Canteen Creek, but it might be better described as a slaughter. The 14 Americans killed every Osage, including women and children. The assault happened at night, with dozens of Osage men, women, and children sleeping in a large lodge. One of the participants in the battle, David Everett, recalled 60 Indians present, but Baldwin believes that this number was likely exaggerated. Everett was recalling the attack as an old man, and it is unlikely the Americans could kill all 60 with single-shot muskets.53

Reynolds also dramatizes his account of this battle. According to him, both Uel and his father William were injured. Uel suffered a shot to his arm, making him unable to operate a gun, while William thought he had suffered a mortal injury. Lying prone, he urged his men to keep fighting, not give up an inch of ground, and not let the Indians touch his body once he died. Uel, unable to fight, examined his father’s wound and discovered that the bullet had not gone through the body. Instead, it had bounced against his ribs and “glanced off towards the spine.” It had lodged near the skin. Uel took out his knife and, despite his own injury to his arm, cut the bullet from his father’s body. He said, “father, you are not dead yet.” William jumped to his feet and cried, “Boys, I can still fight the Indians!” Supposedly none of the 14 men died, while all Indians were slaughtered. Their bodies were left to lay where they died; leaving their skeletons behind for many years.54 This served as a warning to future Indian raiders.55

After the battle on the way back to Whiteside’s Station, the Whitesides and company stopped in Cahokia to dress the wounds of William and his son Uel. In 1795 Cahokia was largely French, so they stopped at the home of one of the Anglo-Americans then living in Cahokia: Elizabeth Raines, the widow of Abraham Raines. William Bolin and Uel became acquainted with Elizabeth’s two daughters: Sarah and Ann. As Reynolds writes, likely romanticizing the incident, William B. was “quite young and very handsome and at last the two brothers married the two sisters… It is singular that such small circumstances may decide the destiny of a person during life.”56

Uel and Ann were married that year on December 29 in St. Clair County. There is no existing marriage record for William Bolin and Sarah, but their first daughter was born in 1799. She was given the name of her mother. Before moving to the Goshen settlement they had a second daughter, Mary Elizabeth, in 1801.57

Yet the Battle of Canteen Creek did not solely yield positive results for the Whitesides. The August 3, 1795 Treaty of Greenville attempt at armistice was threatened by the Whitesides’ indiscriminate slaughter of the Osage a month or so after the treaty was signed. Government officials tried to have William Bolin, Uel, and their father indicted for killing Indians in 1797, as indicated by a subpoena issued for relatives and friends of the Whitesides to testify against them before a Cahokia court.58 However, according to Baldwin, Gov. Arthur St. Clair concluded the attack was justified as the armistice had not yet become widely known in Illinois. He wrote, “Had the matter been ever so criminal in nature it would have been, I believe, impossible to have brought the actual punishment.” As Baldwin writes, frontier juries never convicted Indian killers. In 1795, juries in Cahokia and Kaskaskia refused to convict members of a mob who lynched Potawatomi prisoners near Bellefontaine.59 From the settlers’ point of view, violence against Indians was always justified on the frontier.

This was not the only legal problem encountered by the Whitesides in the 1790s. Most notably, several of them, including William Bolin, were accused of breaking into the plantation of James Piggot and carrying away a freed black couple, Bob and Teria. They were previously the property of William Bolin’s uncle, Thomas, who had died in 1795. Bob and Teria sued for their freedom against the estate, and Judge James Piggot declared them free on January 8, 1796, “for bringing them into a Land of freedom out of slavery.” Piggot was trying to maintain the Northwest Ordinance’s prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory, despite many attempts by slaveholders to keep their slaves. He further awarded Bob a mare, a male horse, and a rifle, that Bob claimed as his property.

The Whitesides were clearly not satisfied with Piggot’s ruling, as on June 10, 1796, a group of Whitesides and others broke into Piggot’s home to reclaim Bob and Teria. Likely Piggot had hired Bob and Teria as servants or farmhands. William Bolin, William Lot, Francis, Isaac, and Adam Whiteside were all accused of the crime, as well as Margaret Whiteside’s sons Michael and George Monroe, along with John Wilson and Seth Chitwood. Piggot gave the following testimony:

On the morning of the day aforesaid before sunrise the aforesaid rioters came to the plantation of this subscriber at the Great Run in the county aforesaid. And being armed with guns, pistols, and swords did in my vue [sic] brake [sic] open the door of the dueling house whair [sic] in resided a peaceable malatto [sic] man & his wife cussed the man with violence and indeavored [sic] to tye [sic] him I entered the house in the same min nit [sic], and in the execution of my office commanded the peace and ordered the rioters to disperse. And there upon two of the rioters took holt of me one of which took me by the throat and a third one drawing a harmons [sic] sword swore he would shave sum [sic] of us and most confidently ordered me to show them my authority. And more over not think to rais [sic] men to suprise [sic] them, for they could rais [sic] more men against me than I could to support my authority.

It is unclear whether the Whitesides and their allies were convicted of the crime, as the documents related to the case are limited in detail. The earliest dated document is from July 6th and calls for the St. Clair County sheriff to bring Adam, Davis, Samuel, and Isaac Whiteside, as well as Michael Monroe, to court for the crime, so it was likely a warrant. It is unclear why Samuel and Davis Whiteside were only named on this document and why none of the others brought before the Grand Jury were not. The next is from July 25th and names all of those I listed first as appearing before the Grand Jury. William Whiteside (presumably William Bolin), William L. Whiteside, Isaac, George and Michael Monroe, Seth Chitwood, and John Wilson, everyone from the Grand Jury except Francis Whiteside, were all listed in another document from August 10. They were all required to pay $1,200, presumably some sort of bond or bail, and appear before the court the first Tuesday in October. None of the remaining documents related to this case list any sort of conviction or punishment and are undated. Piggot’s testimony and evidence that Bob and Teria were freed are undated, so it is unclear if they were presented in court on August 10 or to the court in October. It is possible all documents from the October court are lost.60

In any case, William Bolin did not suffer long term consequences for his kidnapping of Bob and Teria, as he would later serve as sheriff. Still, there were numerous other crimes William Bolin committed. He, Uel, and his father were accused of aiding Elias Fisher in stealing five horses, also in 1796.

Fisher testified that he discussed stealing horses from Indians with the three Whitesides in the early spring of 1796. Uel in particular said Fisher would be justified in stealing horses from the Indians, as Indians had stolen horses from Fisher. On June 11, according to Fisher, he and William Bolin left Whiteside Station for Cahokia to steal horses. They found a group of five horses near the village of Prairie du Pont (now known as Dupo) just south of Cahokia. William Bolin believed only Indians let their horses range that close to Prairie du Pont, so the pair gathered the five horses and brought them to a spot two miles away from Whiteside Station. William B. then told his father and brother what they had done. His father warned him to be careful and keep the theft secret, as while he believed stealing horses from Indians was justified, other whites disapproved of any horse theft, even against Indians. Uel agreed.

The next day, William B. and Fisher left to sell the horses in Kentucky. Along with his father, William B. agreed to sell the horses under Fisher’s name, but William B. would receive half the profit from the sale. Here is a list of each horse and their destination:

Unfortunately for the Whitesides and Fisher, when they returned there was “noise made about the stolen horses.” Apparently the horses did not belong to Indians, but instead to various Anglo-Americans, namely James Piggot, William Arundel, Louis Gervais, John Baptist Lolarde, and Charles Germain. Fisher, according to his testimony, hoped to come to pay the horse owners back to settle the dispute, and the elder William Whiteside offered to pay. However, Fisher was arrested for horse stealing and held at the jail in Cahokia and gave the aforementioned testimony accusing the Whitesides of aiding and abetting his theft. The Whitesides were then themselves indicted for horse stealing.

It is possible Fisher acted alone and lied in his testimony, as the previous year he was accused of trespassing against the three Whitesides. Thus he accused them for revenge. However, John Johnson Whiteside, William B.’s cousin, testified that he saw the horses outside Whiteside Station the same day Fisher and William B. left for Kentucky and knew they did not belong to the people of the station.

Once again, there are no records of the eventual conviction or punishment, though The Laws of Indiana Territory claims that the horse stealing case was continuously deferred.61

Finally on August 31, 1798, the St. Clair County sheriff was ordered to bring William B. Whiteside and his cousin William Lot Whiteside to court to answer concerning “divers trespasses, contempts, riots, assaults, and offenses of which they stand indicted.” The exact nature of these crimes is not discussed in detail, and may refer to the previously mentioned crimes.62

While these crimes are somewhat serious, it seems they did little damage to the Whitesides’ reputation. Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison, the future president, appointed three of the Whitesides as justices of the Quarter Sessions despite being indicted for horse stealing. Presumably these were William Sr., William B., and Uel. In 1809, Shadrach Bond Jr. and William B. disputed the office of lieutenant-colonel of the St. Clair County militia, and governor Ninian Edwards asked Bond to enter into an election to resolve the dispute.63 Bond refused. He wrote back to governor Edwards:

I shall send you the Certificate of Thomas Todd Esqr which will enable you to judge whether or not Whiteside has been that terror to Disorganisors as represented in his Potition [sic]. he has been indited [sic] for horse stealing and now lies under an inditement [sic] in this County Court for harboring runaway Negroes, these with other reasons I believe induced governor Harrison to give me the appointment over Whiteside — as I never wrote to brake on the Corrector [character] of anyman, I am sorry to be compeled [sic] to Do it now nor would I but to show your Excelency the Corrector [character] of the man which you Propose for me to go into an election with .... I cannot condesend [sic] to put myself on a level with such a character as Major Whiteside64

Laws of Indiana Territory speculates that Edwards chose William B. over Bond for political reasons, as Edwards had previous disagreements with Bond.

It is likely that the Whitesides did not suffer significant consequences because frontier Illinois was fairly lenient with crime. Because workers were scarce, lengthy incarcerations and executions cost society valuable labor, so these punishments were only reserved for the most serious of crimes. Fines and indentured servitude were far more common punishments.65

Frontier attitudes about crime as seen through the Whitesides, criminals who became agents of the law, is a rich topic worth exploration for future researchers.

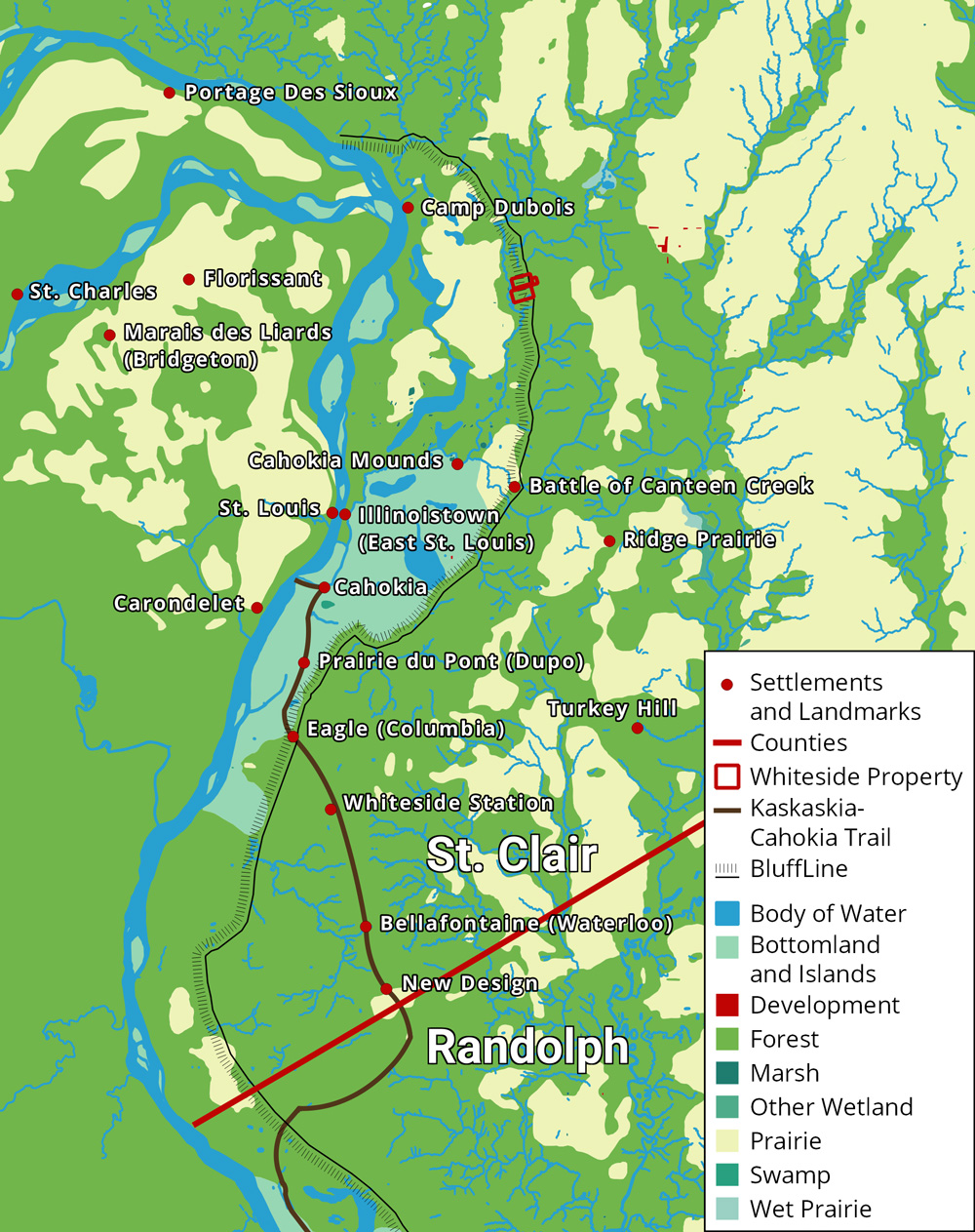

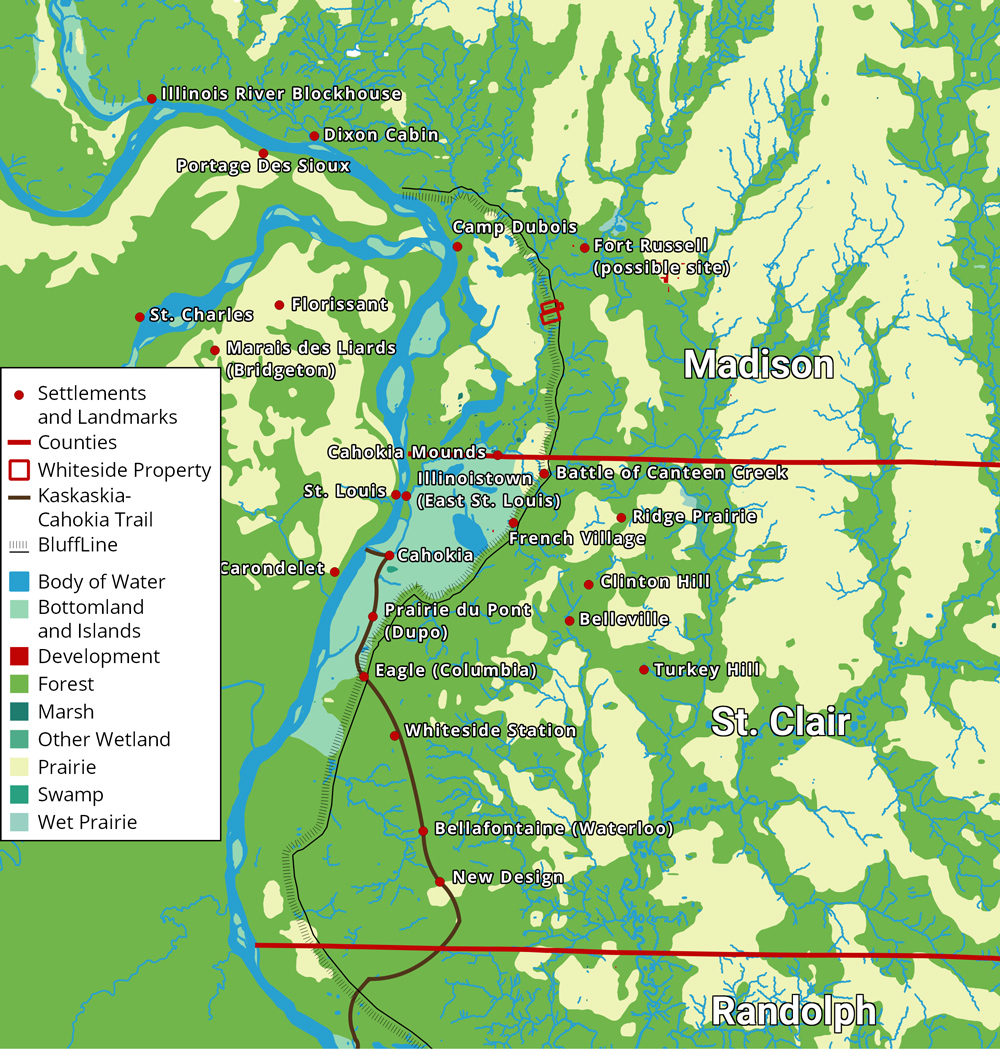

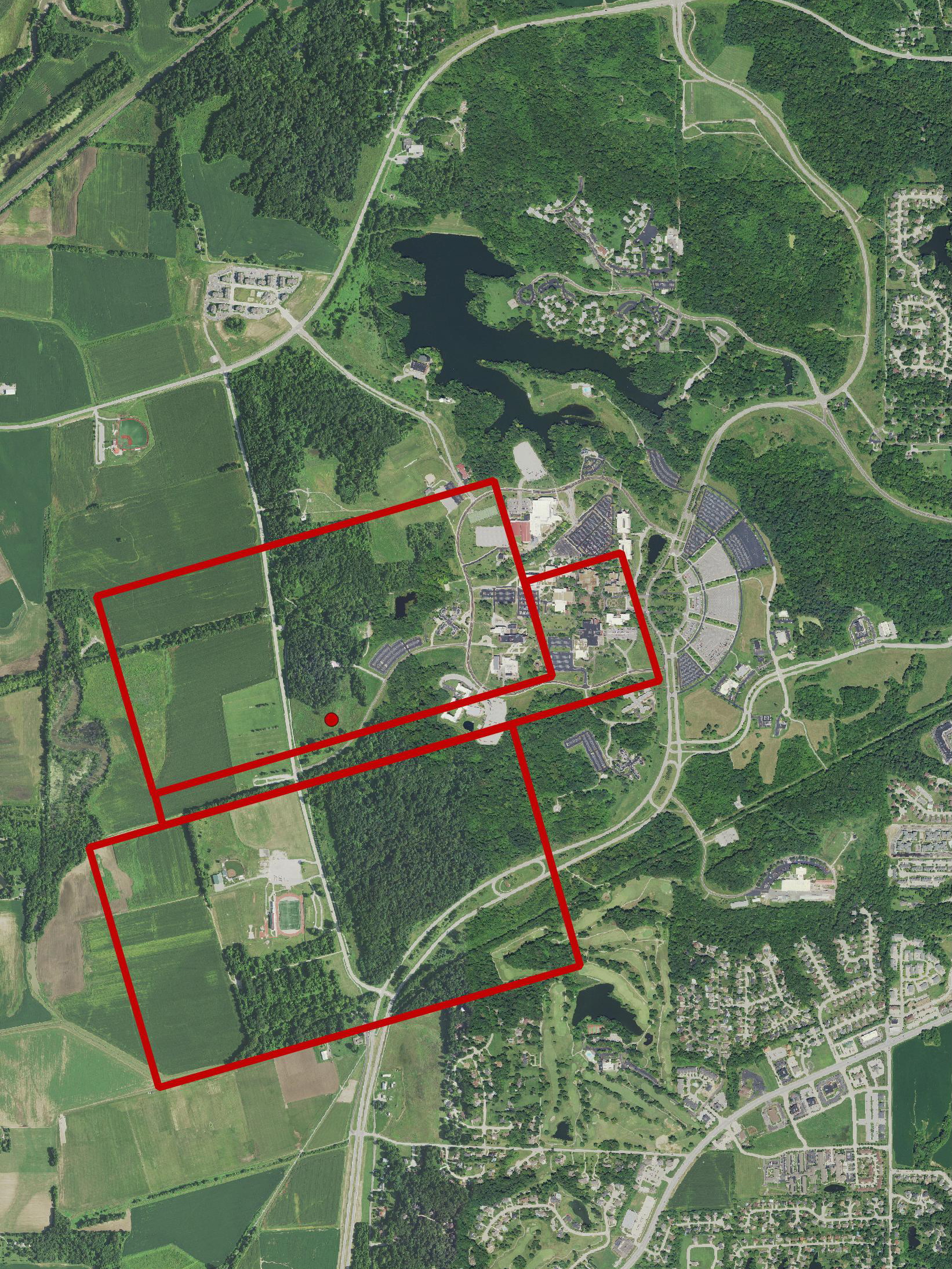

With relative peace reached with Native Americans, many of the younger Whitesides, along with a number of other settlers, migrated a short distance north to the new settlements of Ridge Prairie and Goshen in 1802, according to Reynolds.66 It was likely then that William Bolin, his brother Uel, their wives Sarah and Ann, along with their young children, established their settlement on the land that would become part of the SIUE campus in the Goshen Settlement. Other Whitesides may have lived with them as well.

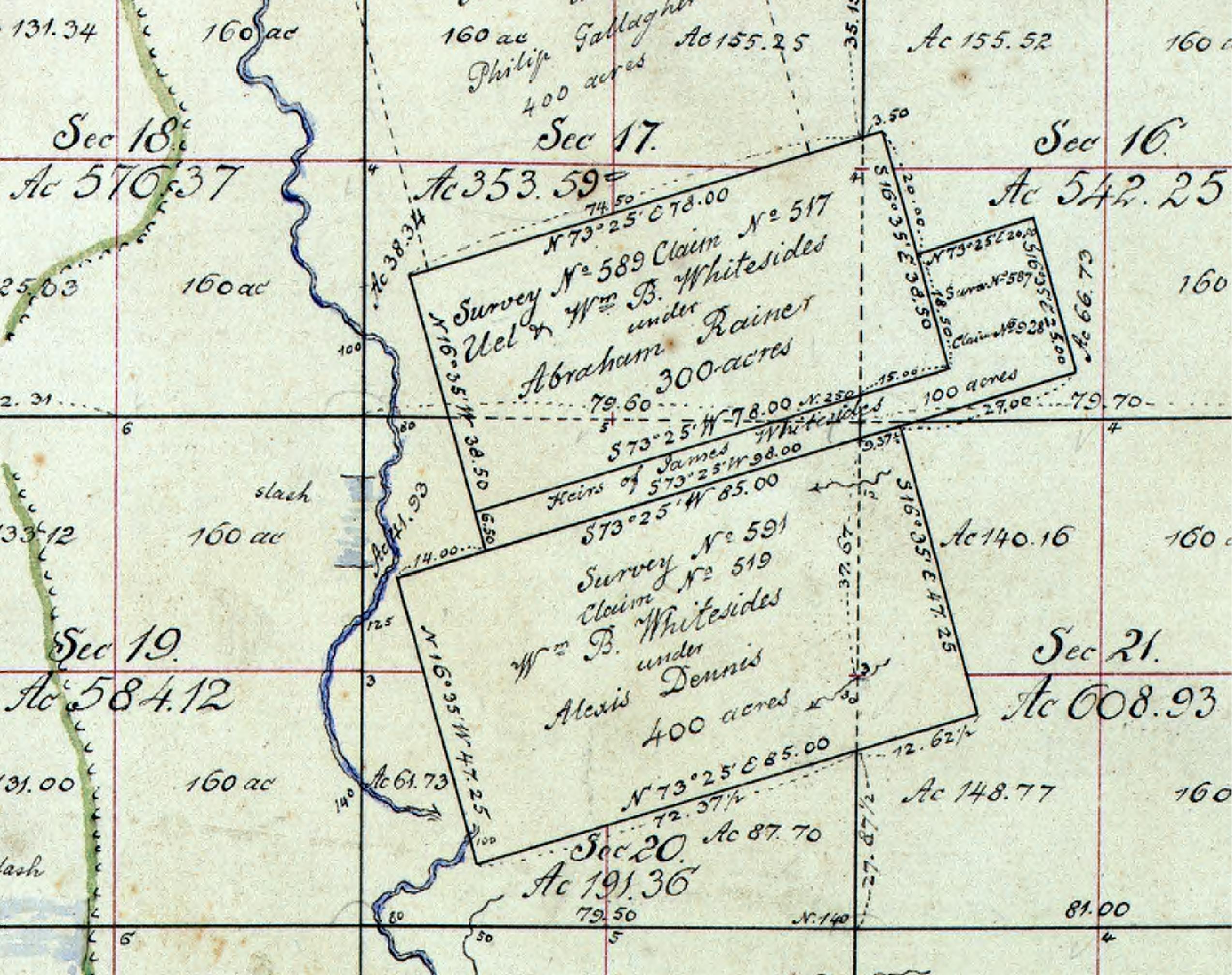

In an 1815 plat map of the Edwardsville Township, three land claims are located in one cluster along Cahokia Creek, all claimed by the Whitesides. The 300-acre land claim furthest north belongs to both William Bolin and Uel Whiteside, with the original claimant listed as Abraham Raines, their deceased father-in-law.67 The brothers had presumably inherited the land through their marriages to Abraham Raines’ two daughters.68 Abraham Raines or his widow Elizabeth were donated the land as part of an act of Congress which granted 400 acres to each head of family in “the district of Kaskaskia.”69 The Congressional record states that the claim was 400 acres, while the plat map shows only 300.70

The 400-acre claim furthest south belongs to just William Bolin, with Alexis Dennis listed as the original claimant. Less is known about this original claimant, who is also occasionally referenced as Alexander Dennis. Reynolds describes the death of a man named Dennis, likely the same man:

A small impediment to the growth of the [Goshen] settlement was the killing of Dennis and Van Meter by the Indians in 1802. Turkey Foot, an evil-disposed and cruel chief of a band of the Pottawatomie Indians, and his party, returning home from Cahokia to their towns toward Chicago, met Dennis and Van Meter at the foot of the Mississippi Bluff, about five miles southwest of the present town of Edwardsville. The country contained at that day very few inhabitants above Cahokia, and Turkey Foot, seeing the Americans extending their settlements toward his country, caught fire at the spectacle and killed these two men. These Indians may have been intoxicated, as they were frequently drunk when they were trading in Cahokia. This was not considered war, but a kind of Indian depredation.71

The final land claim is a smaller strip listed as belonging to “the heirs of James Whiteside.” This strip was only 100 acres and was granted to James Whiteside as part of “a list of militia donations granted by the Governors of the North-West and Indiana Territories” on January 4, 1813.”72 It is unknown if this is William B.’s uncle James who died in 1790 or his younger brother James, who died in 1794, or yet another James Whiteside. It is also odd that it was granted by “the Governors of the North-West and Indiana Territories,” since by 1813 Illinois was a territory. It is possible their uncle James was granted the land for his service in the American Revolution and William B. and Uel were his heirs.

Land speculation was very common on the frontier, where settlers would buy land as soon as it was for sale and then sell it later for a profit. William Bolin was no exception, owning land in Alton, Bethalto, and other areas in Madison County by his death in 1833. Yet there is little doubt William Bolin had made his residence along these claims, based on numerous sources and the fact that he is buried on the land.73

On December 31, 1809, William Bolin’s southernmost claim in the Goshen Settlement was recommended for approval “on the ground of actual improvements having been made.” It was among 12 claims in present day Madison County recommended for approval by land commissioners. These commissioners defined these improvements as “not a mere marking or deadening of trees, but the actual raising of a crop, or crops, such, in their opinion, being a necessary proof of an intention to make a permanent establishment,”74 meaning the Whitesides had already “improved” their land with the raising of crops by 1809.

The southern claim was described as:

‘Claim 519. Original claimant, Alexander Denis; present claimant, William Bolin Whiteside; 400 acres, on Winn's run in the county of St. Clair (St. Clair and Randolph were then the only counties), beginning at a white walnut near Cummin's sugar camp.’ This is in section twenty, township four, range eight, on the bluffs of the American Bottom, in what appears to have been considered at that time the most attractive part of the county, the "Goshen" settlement.75

The northern claim was among five recommended for approval on January 4, 1813:

‘Claim 617. Original claimant, Abraham Rain ; confirmed by Gov. Harrison to the widow and heirs of Rain ; claimants before the former board of commissioners, Uel and Bolin Whiteside, 250 acres’ This is in sections twenty and twenty-one of township four, range nine. On the surveys the name is spelled Rainer.76

With the privileges of a land owner, William Bolin and Sarah expanded their family. Already with two daughters, they had their first son in 1803: Moses, a highly symbolic name. Elizabeth Ann was born in 1806, followed by another daughter in 1807: Hester Ann. William Bolin Jr. was born in 1810, the last child before the War of 1812. After the war, Elvira and George Washington were both born in 1814, likely twins. Finally Ninian Edward was born in 1819, named after Illinois’ territorial governor.77

It is highly likely that either William Bolin or Uel met William Clark while he and the Corps of Discovery were wintering at Camp Dubois in the winter of 1803 and 1804. Clark mentions their father visiting the camp on January 2, 1804 in his journal:

Snow last night, ⟨rain⟩ a mist to day Cap Whitesides Came to See me & his Son, and some country people …Mr. Whitesides says a no. of young men in his neghborhood [sic] wishes to accompany Capt. Lewis & myself on the Expdts78

William B. was appointed captain in 1802, but his first son Moses would have been an infant. Either William Bolin or Uel could be the son they refer to, or perhaps their younger brother Robert. William B. and Uel were far more prominent locally, so it was probably one of them, or perhaps both came and Clark did not remember the older Whiteside having two sons. Though many members of the Corps of Discovery were volunteers from the American Bottom, William R. Whiteside does not believe any people from the elder Whiteside’s neighborhood (still Monroe County) actually went along.79

Clark makes further mention of an unknown Whiteside who visited two days later. He sold the Corps of Discovery commissary 12 pounds of tallow, beef fat used for soap making, at $3 per hundredweight.80 This could be any number of Whitesides.

Clark makes a final mention of a Whiteside on January 31. He and Lewis were heading up “the river” (likely the Mississippi), which he described as “ice running.” The Mississippi was frozen over during the especially cold winter of 1804, so they either navigated between frozen areas on the river, or had to walk alongside it. In either case, Clark writes, “Mr. Whitesides & Chittele crossed from the opposit Side of the Mississippi.”81 It is unknown which side either party was on or, again, if the Mississippi was even navigable. However, Clark seems to recognize this particular Whiteside from a distance, indicating that he knew him well enough to recognize him.

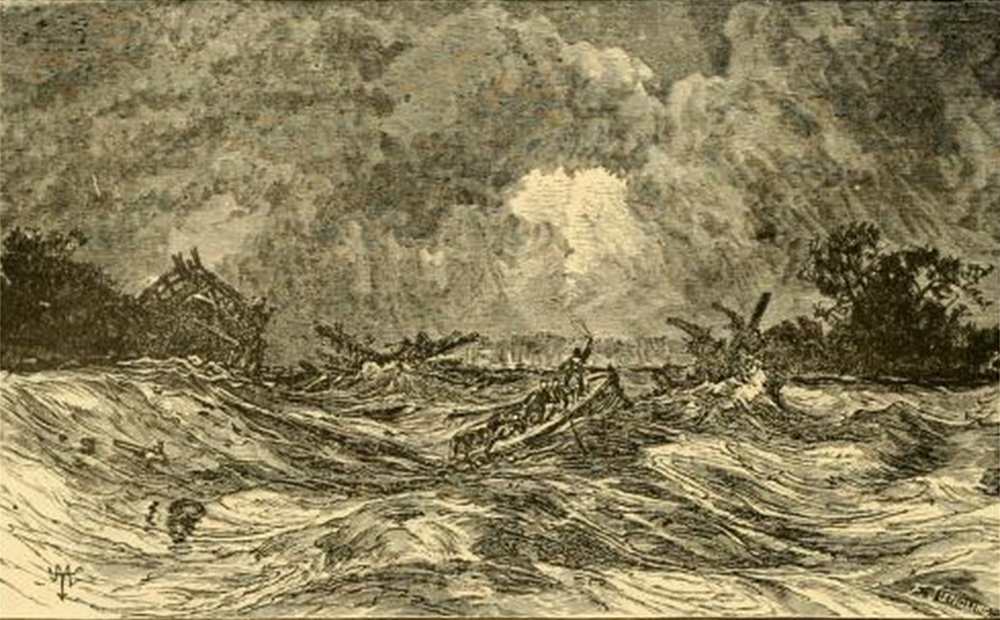

As relative Indian peace started breaking down in 1810, William Bolin also experienced a series of major earthquakes in the winter of 1811 and 1812. We do not have record of the Whitesides’ experience in the earthquake, but based on other eyewitness accounts it was likely harrowing.82

To deter the rise in Indian attacks, in 1811 Congress authorized the creation of 10 companies of mounted Rangers to protect Anglo-American settlers in the Northwest Territory. Four of these Ranger companies were charged to protect Illinois. Because of his military experience, William B. Whiteside was appointed captain of one of these companies, and his cousin, Samuel Whiteside, was appointed captain of another.83

As captain, Whiteside was responsible for the protection of his family from Indian attacks. His company traversed the landscape between settlements in search of Indian bands poised to attack. They both prevented raids and pursued Indians following attacks. Whiteside though was required to supply his own horses and equipment, but was paid $1 a day.84

I have not focused closely on Whiteside’s precise activities during the war, though I am sure there are plenty of records. I leave that to future researchers. John Reynolds served under Whiteside during the War of 1812, so it is worth looking at his account of his experiences in the war to determine what Whiteside was doing.85

One likely development from Whiteside’s war experience was a relationship between him and Illinois’ territorial governor, Ninian Edwards. Shortly after the war in 1819, Whiteside named his youngest son after the governor, just as Edwardsville was named for him around this time.86

We also have record of three letters from the War of 1812 because they were in the papers of Ninian Edwards. Two were sent to Whiteside, one sent from Whiteside to Edwards.

The first letter was written by Samuel Whiteside to his cousin William Bolin, from a block house or small fort near the confluence of the Illinois and Mississippi on July 24, 1811. Samuel writes, “I conceive it my duty to give you a statement of an affair that took place here since you left the block house.” He then spends the letter describing a confrontation between the residents of the fort and a group of Sac Native Americans and French the day before.

Samuel writes that the militia stationed at the fort have treated all travelers up and down the Mississippi, “both Indians and whites,” with civility until the day before. That afternoon they discovered “two canoes on the river near the Louisiana shore;” the opposite side of the Mississippi. Following the orders of William Bolin, Samuel says they hailed the passengers of the canoes for them to come to the fort, but they did not. Instead, they slipped alongside one of the islands at the confluence. Samuel took two men along to meet them. Once near enough to the canoes to hear the strangers talking, Samuel hailed them again. He told them he was ordered to determine what Indians passed by the station. One of the Frenchmen responded in what Samuel considered “very insulting and abusive language,” and they continued up the river. Samuel warned he would fire on them if they did not stop, and the Frenchman replied, “Fire and be damned!” Samuel shot ahead of the canoe about twenty or thirty feet. The Frenchman grew angry and fired at Samuel, nearly hitting him. Samuel was “irritated, knowing they must have seen I did not aim at them.” Samuel returned fire, but he did not believe he hit the Frenchman as he was two or three hundred yards away, which is odd since he said the Frenchman had nearly hit him. The canoe men fired at the Anglo-Americans with two more guns, but did no damage. The Anglo-Americans returned to the station.

Samuel then writes that the day before that, July 22, a Sac Chief had come and told the Anglo-Americans that Indians would follow him in the evening and stop at the station. Samuel writes:

It appears to me that it was the Frenchman’s fault, as we told the Indians very civilly, in their own language, what we wanted with them and that we would not detain them. I shall be extremely sorry to have done anything that may have the least appearance of an unfriendly disposition towards Indians that is [sic] in friendship with the United States. A man that called his name Blondo came down the river and had met several canoes of the Sac Indians this morning [July 24], not far above this place, who told him they had been fired on the evening before by the people of this Block House, and that they were very angry in consequence of it. I, not being acquainted with the nature of Indians, may have done wrong; but I have this consolation, if I have, it was with an intention of doing right.87

This incident angered the governor of the Louisiana Territory, Benjamin Howard. He wrote a letter on July 27 to Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards expressing his displeasure. He stated that the group the Illinois militia fired on were a party of Sac Indians with women and children on their way from St. Louis to Fort Madison. He writes from St. Louis:

I cannot believe that this act can be justified by any instructions from you. The white man who was with the chief, and ahead of the party, when this affair took place, says that when they came up they appeared much irritated. I expect everyday some chiefs from the Sacs here, and I think it important that the transaction should be satisfactorily explained to them. These people are powerful and now very friendly towards us, and 'tis possible that this affair may have a tendency to change their disposition in regard to the Americans.88

Ninian Edwards then wrote to William Bolin Whiteside on August 2 regarding Howard’s letter. I have not found this letter, but William Bolin responded from Goshen on August 4, including with it a copy of Samuel’s letter. He writes:

I have written to Governor Howard and given him all the information in my power and that will be satisfactory to him, I hope. I do inclose to your Excellency a copy of a communication made by the officer to me, giving the whole narrative of the transaction that took place with respect to firing on the Sac Indians. I can only observe that I think the boys was [sic] rather too forward, but I believe it was done by the officer without considering what the consequences that might result from it would be. Altho' I know him to be a deliberate man and one as zealous for the safety of his country as perhaps any one in it.

I am very Respectfully your

Obedient Servant,

Wm. B. Whiteside.89

On February 7, 1812, 18 militia officers of St. Clair County met in Cahokia to discuss the Indian situation. Patriarch and Colonel William Whiteside was appointed chairman of the meeting. Also present were a Major Whiteside and Captain Whiteside, presumably William Bolin and Samuel respectively. At this meeting the officers issued two resolutions expressing their displeasure regarding Indian attacks and listed recommendations to the government of Illinois. I analyze these two resolutions on War of 1812 Ideology.90

Finally, William B. received a letter from Ambrose Whitlock on August 18 that seems to be concerned with military salaries. I leave it to future scholars to decipher.91

One year after the war ended, 1815, Illinois patriarch William Whiteside died at the age of 68, likely of natural causes. Possibly there was a disease outbreak in the American Bottom from the soldiers returning from the war, much as there would be in 1833 following the Black Hawk War, but it could just have easily been old age. In any case, according to Reynolds the elder Whiteside died and was laid to rest at Whiteside Station.92 In addition, his younger brother Uel died in 1818 of unknown causes, and William Bolin served as executor of his estate.93

Though he lost his father and brother, Whiteside could settle down after the war and “tame the wilderness” as a peacetime farmer. His last child was born shortly after the war, Ninian Edward in 1819, and served as the sheriff of Madison County.

In 1816, William Bolin killed 14 wolves and claimed a bounty of 75 cents each for a total of $10.50, likely to protect his livestock. He killed by far the most in the county that year: about 11 percent of the total 121 bounties claimed. In second place was William Howard with nine scalps. His cousin Samuel only killed three.94

On March 15, 1817, William B. Whiteside wrote a letter to his cousin William F. Whiteside, the son of the late Davis Whiteside who had died at King’s Mountain. William F. was still living in North Carolina. In the letter, William B. describes the health and status of various members of the Whiteside family, including describing his uncle John as “inSain [sic] and has got intirely [sic] helpless.” Still, Whiteside writes, “We have now peace with the Indains [sic] and people Emigrits [sic] to our country very fast and I am sure we have one of the best Countrys [sic].” Numerous details in this letter are worth pursuing for future researchers. In general, it indicates a lasting connection between the Whitesides of Illinois and the remaining Whitesides of North Carolina. William B. even tells William F. that “if they were to change N. Carolina for the Illinois they will get the Best of the Bargain.”

The main purpose though of the letter is slavery. William B. indicates that their shared uncle Adam Whiteside made an agreement with William B.’s father to retrieve an enslaved girl from the Louisiana territory. His father and Adam entered a bond of $1000. However, Adam never returned or sent any letters back. William B. thus discusses legal matters with William F. to earn recompense for the $1000. I leave it to future researchers to sort out the legal details.95

Whiteside was undoubtedly a slave owner, as were a number of his relatives. They were among the many settlers from the south who brought their slaves with them to the supposedly free Northwest Territory, usually skirting the prohibition of slavery by signing their slaves on as indentured servants.

In addition to the controversy with Bob and Teria I discussed previously, here is a list of known people owned by William B. Whiteside or his brother Uel. As is often the case with enslaved people, they are often given a physical description:

William R. Whiteside has further records of enslaved people owned by various other Whitesides.

With this evidence alone, it is easy to demonize Whiteside as a slave owner. Yet this is complicated by a convention address signed by a William Whiteside of Madison County from the summer of 1818. This address was part of the statehood convention, signed by 13 men, and gave strong opposition to efforts to maintain slavery in Illinois under the state constitution. It reads:

We are informed that strong exertions will be made in the Convention to give sanction to that deplorable evil in our state… we therefore, earnestly solicit all true friends of freedom in trying to defeat it…99

Both William R. Whiteside and The Laws of Indiana Territory do not think the “William Whiteside from Madison” is William Bolin.100 Given the frequency of the name William Whiteside, they may be right, but owning slaves and opposing slavery are not mutually exclusive. Thomas Jefferson believed slavery to be morally wrong yet owned hundreds of slaves. Whiteside might have been of a similar mindset; holding profound moral qualms about the institution yet unable to free himself of it for financial reasons.

It is also possible that Whiteside himself differentiated between the chattel slavery of the south and the pseudo-slavery and indentured servitude system he participated in. Perhaps he justified the system as a paternalistic way to help freed slaves. Whiteside also may have wanted to stop the spread of official slavery to avoid competing with planters who owned hundreds of slaves. This was the frequent criticism of slavery from yeoman farmers like Whiteside.101 As a small slave owner, Whiteside benefited financially from restricting the flow of slavery into Illinois.

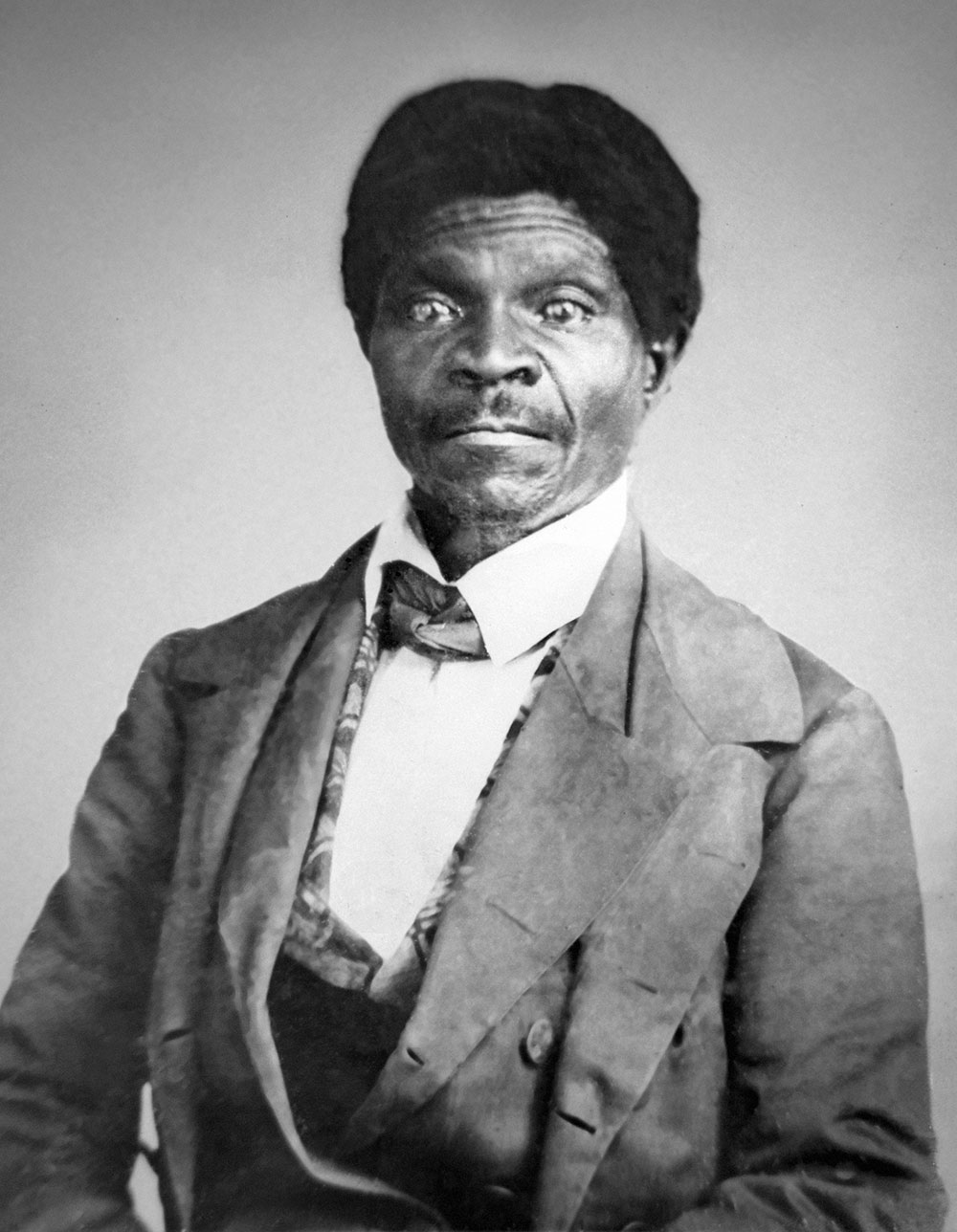

Perhaps the most significant role any Whiteside would have in American history resulted from the issue of slavery. An enslaved woman, Winny, successfully sued for her freedom from her owner, the widow Phebe Whiteside, in Missouri. The case helped set the legal basis for Dred and Harriet Scott’s lawsuit for freedom in St. Louis in the 1850s.

Phebe and John Whiteside were relatives to William Bolin, but their connection is currently unproven, according to William R. Whiteside. Court records state they came from “Carolina” in 1794 or 1795 to Illinois, bringing the enslaved Winny with them. William R. Whiteside is uncertain if they came with the rest of the Whitesides at that time or came after. He told me that records indicate they stayed at Whiteside Station for a time, implying a relationship between the different Whitesides.

John, Phebe, and Winny stayed in Illinois for a few years before moving to St. Louis in 1798 or 1799. They continued to hold Winny as a slave, and John died shortly after 1814.

Winny sued Phebe for her freedom in 1818. We can only speculate why she waited 20 years after first moving to the supposedly free Northwest Territory to seek freedom. Perhaps she had met others in St. Louis who told her she could sue for her freedom. By then she was in her thirties with nine children, some of whom might have been nearing legal age. She might have hoped to gain their freedom as well.

Possibly because of legal reorganization upon Missouri’s statehood in 1820, Winny’s case did not reach trial until 1822. The jury decided in favor of Winny and awarded her $167.50 in damages. Phebe appealed and the case reached the Missouri Supreme Court in 1824, which also decided in Winny’s favor because she had lived in a free territory.102

Winny v. Whitesides set crucial legal precedent in Missouri: that a slave could sue for freedom on the basis of living in a free territory. Missouri courts freed ten slaves on this basis over the next thirteen years. Dred and Harriet Scott’s lawyers used Winny v. Whitesides as a legal basis in their freedom suit in 1846, but by then slavery advocates were far more entrenched. The Scotts’ case famously led to probably the most disastrous Supreme Court decision ever in 1857, in which Chief Justice Roger Taney declared African Americans were “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." Backlash to this decision helped ignite the American Civil War.103

The Whitesides held a complex relationship with slavery, one which reveals the many dimensions of the peculiar institution in frontier Illinois. It is a rich topic worth further examination.

William B. also served as sheriff of Madison County once Illinois became a state. In the first election in Madison County under the state constitution on September 17, 18, and 19 in 1818, William B. won with 260 votes, the incumbent sheriff Isom Gillham received 169 votes, and Joseph Borough 106.104 Gillham had previously served as the first sheriff of Madison County from the county’s founding in 1812 until the election of 1818, making Whiteside the second sheriff and the first under the state government.105

Court records from 1819 to 1821 indicate that, as sheriff, Whiteside was responsible for tax collection and management. For example, on September 8, 1819, he was paid $15 for “making out an alphabetical tax list for the year 1819.”106

During his time as sheriff, Whiteside and his deputy, Robert Sinclear, were accused of robbing the home of Richard Dixon, which likely caused Whiteside to lose his position as sheriff. For obvious reasons, this case sparked a great deal of excitement and controversy in the area.

The two most complete accounts of the robbery were written many years after the fact: History of Greene and Jersey County from 1885 and Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois, and Its People, 1812 to 1912. Both give the same general narrative: in the summer of 1821 the home of the elderly Richard Dixon and his wife was invaded by robbers. These men carried off a considerable amount of money (History of Greene and Jersey County says $1200), and when Mr. Dixon and his friends went in pursuit, they discovered the robbers were Sheriff William B. Whiteside and deputy sheriff Robert Sinclear. Both were put on trial for the robbery.

The Dixons lived near the mouth of the Piasa Creek, which in 1821 was just across the border in the newly formed Greene County. Today their home would be in southern Jersey County northwest of Alton. As a result, the trial was held in Carrolton in Greene County in 1822 and was presided over by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Illinois, Joseph Phillips. John Reynolds, then a justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, had also done a preliminary investigation into the case, despite his previous relationship with Whiteside. Whiteside and Sinclear both plead not guilty. Despite what appeared to be a fairly conclusive case against Whiteside, the jury could not reach a conviction. Whiteside was friends with one of the jurors, Charles Kitchens, and while the remaining 11 jurors wanted to convict, Kitchens’ voice for acquittal led to a hung jury. The case was delayed, and during that time Richard Dixon died. Without a key witness, Whiteside was cleared of the robbery.

Sinclear was less lucky, as the jury managed to find him guilty. He shortly thereafter though managed to escape to Arkansas, where he went on to serve in the Arkansas legislature.107

Unlike the other court cases against William B., this one has a significant number of surviving court papers from 1822, which is likely why both county histories were able to discuss it in detail. The documents agree with the major details of both narratives. It is possible that there is a minor detail that they get wrong, which I leave to future researchers to figure out. In particular, one document gives the precise amount stolen as $1209.64, and another states the precise time the robbery occurred: June 20, 1821 at 2 am. Given that other documents regarding the arrest of Whiteside and Sinclear are dated June 21, this is likely correct.108

The case is mentioned a couple other places. The Laws of Indiana Territory 1801 – 1809 (published 1930) mentions it briefly in its biography of the Whitesides and cites History of Greene and Jersey County.109 Finally, Gershom Flagg of Edwardsville mentioned the robbery in a letter to his mother dated October 4, 1821. In listing the recent news of the area, he describes the robbery. Flagg erroneously writes that the robbery occurred in July and also states that $1200 was all the money Mr. Dickson (as he spells it) had. He further writes that the robbery took place on a “dark rainy night,” which made it easier for the robbers to be caught. Given that he got the date wrong, the description of the robbery taking place in the rain must be read with suspicion. It is possible that detail was added to the story by the time Flagg heard it. Still, he is useful in describing the community’s reaction to the Sheriff and the Deputy committing the crime, writing, “Both of whom have heretofore been considered citizen of the highest respectability.”110

Unfortunately, none of the documents from the 1820s suggest a motive for Whiteside aside from the obvious financial gain. However, the 1912 Centennial History of Madison County gives Whiteside potentially heroic motives. In one version of the story, Richard Dixon’s son, Matthew, had died at some point prior to 1821. Before his death he had given several thousand dollars to his father, and his widow claimed right to the money. Dixon refused, and the widow went to Sherriff Whiteside and his deputy Sinclear. Moved by her story, they resolved to take the money from Dixon themselves and then gave it to the widow, minus a small amount for “expenses.”

This “Robin Hood” explanation certainly fits with Whiteside’s history of taking the law into his own hands, but it is not without its problems. Even the authors of Centennial History of Madison County do not fully trust its veracity. They reference the 1864 recollections George Churchill, a local anti-slavery politician at the time, who believed that the widow explanation was invented by Sinclear when rumors of the robbery followed him to Arkansas. If the story were true, it is odd that none of the documents from the 1820s mention it as part of the legal defense.

Whiteside still received a character defense from another contemporary referenced by Centennial History of Madison, Thomas Lippincott, who wrote alongside George Churchill in 1864. Lippincott was also responsible for taking down the evidence in the case. He writes:

It is due to the memory of William B. Whiteside and his descendants to say that he was always esteemed a good citizen and an honorable man with this single exception. As one of the officers of the Rangers, in the Indian wars, he was always considered the best, being as cool and judicious as he was brave.111

It is also worth noting that John Reynolds, who was part of the investigation, still thought highly of Whiteside in his memoirs I referenced at the beginning.

Still, Whiteside was no longer sheriff after 1822, presumably removed from office due to the accusations of robbery. Nathanial Buckmaster was elected sheriff in 1822, either defeating Whiteside in the election or Whiteside had vacated the office completely. Buckmaster remained sheriff until 1834, one year after Whiteside’s death.112

The Dixon case is filled with many details that I did not look at closely. I leave that to future researchers to sort out.

William Bolin and Sarah’s children also started marrying and having children following the war.

William B.’s remaining three sons were not married until after his death in 1833: George Washington Whiteside in 1839, William Bolin Jr. in 1842, both married in Galena, Illinois, and Ninian Edward Whiteside in 1853 in California.

William B. had numerous grandchildren and further descendants, and it is very possible many have yet to be identified. Some may still live in the area.

Many of these marriages did not last. Moses and Nancy Whiteside divorced in 1833. Baldwin writes that Moses “disappeared several months after marrying the second Nancy Judy and was believed to have been killed by Indians in the wilderness.” After seven years, Nancy filed for divorce in 1832 and remarried in 1833.113

William R. Whiteside has found some details that complicate this story. For starters, Moses did not die in the “wilderness” but remarried in Wisconsin. Further, according to court records for the divorce, the couple had two children: Elizabeth Ann Whiteside and Jacob Judy Whiteside, and the divorce was actually granted in 1833. Moses could not have left as quickly as the story tells. Still, it appears Moses was absent by this point; he never came to court despite being summoned, and the children were put into the custody of Jacob Swiggart, Hester Ann’s husband.

Where then did this story come from? Baldwin apparently had heard it from Emma Schoen, Nancy’s great-granddaughter through a third marriage after her second husband died. William R. Whiteside had called Schoen, who told him that the story had been handed down in their family. Possibly Nancy never heard back from Moses and assumed he had died. Or she did know he left her and remarried and told her children a more palatable story.

Sarah also divorced Robert Reynolds in 1834 and remarried that same year to George Swiggart. She died and was buried with the name Swiggart only one year later, 1835, with her parents, assuming the details on the obelisk are correct. For more on this date problem, see Whiteside Cemetery.

Though Hester Ann was not divorced, her husband Jacob Swiggart remarried six years after she died in 1836. In 1842 he married Mary Nix, the marriage was annulled in 1842, and they were remarried to each other in 1850, after which they had three children.

Elizabeth Ann was not divorced, but widowed in 1850 when her husband Jacob Judy died. There is no evidence of them having children, though they were married for thirty years. She married Dr. John Claypoole in 1853, himself a widower with 5 children and 7 adopted children. Elizabeth and Dr. Claypoole moved to Fort Madison, Iowa at some point. Elizabeth likely moved back to the Edwardsville area after he died in 1866, and she died in 1867 and was buried with her sister and parents. See Whiteside Cemetery for more on her death.

When war broke out once more with Native Americans, this time in northern Illinois, William Bolin and his cousin Samuel participated again, much as they had in the War of 1812.

Both Whitesides participated in the campaign of 1831, which saw limited action. In that campaign, governor John Reynolds responded to Black Hawk’s return across the Mississippi by calling for a militia force of 700 mounted soldiers to force the Sauk and Fox Indians "dead or alive over to the West side of the Mississippi." The two Whitesides ended up among the 1,400 militiamen that went with Reynolds to Rock Island on June 25, 1831 where they met with another force under the command of General Edmund Pendleton Gaines, commander of the Western Division of the U.S. Army. With the threat of war and superior numbers, Gaines managed to force Black Hawk and his band back west of the Mississippi on June 30, 1831 without any significant bloodshed.114

During this brief campaign, Major Samuel Whiteside commanded the Spy Battalion made up of four companies. William B. Whiteside captained one of these companies with about 50 men under his command. The formal name of the company was “Captain William Whiteside’s Company Odd Battalion of Spies of Mounted Volunteers,” and was formally put into service on June 13, 1831. Whiteside had enrolled all but two of the company members that day in Edwardsville. Two days after Black Hawk agreed to move west, July 2, the company was formally discharged and disbanded.115

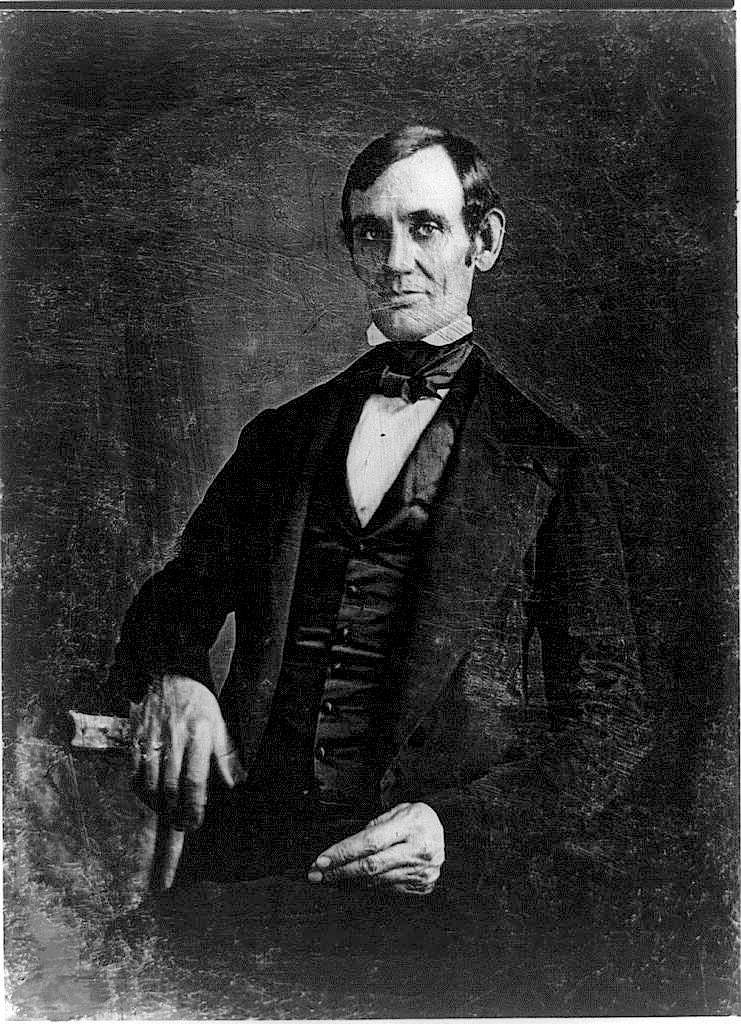

That day, a muster roll was conducted of the company. William B. is listed as the captain and present, but also as sick. Perhaps this is why he is not listed as a commander in the bloodier 1832 campaign when Black Hawk’s band returned. By then, Samuel Whiteside had been promoted to Brigadier General and commanded the first army, known as Whiteside’s Brigade. Under his command was a recently enlisted and promoted captain of one of the companies, a 23-year-old New Salem merchant named Abraham Lincoln.116

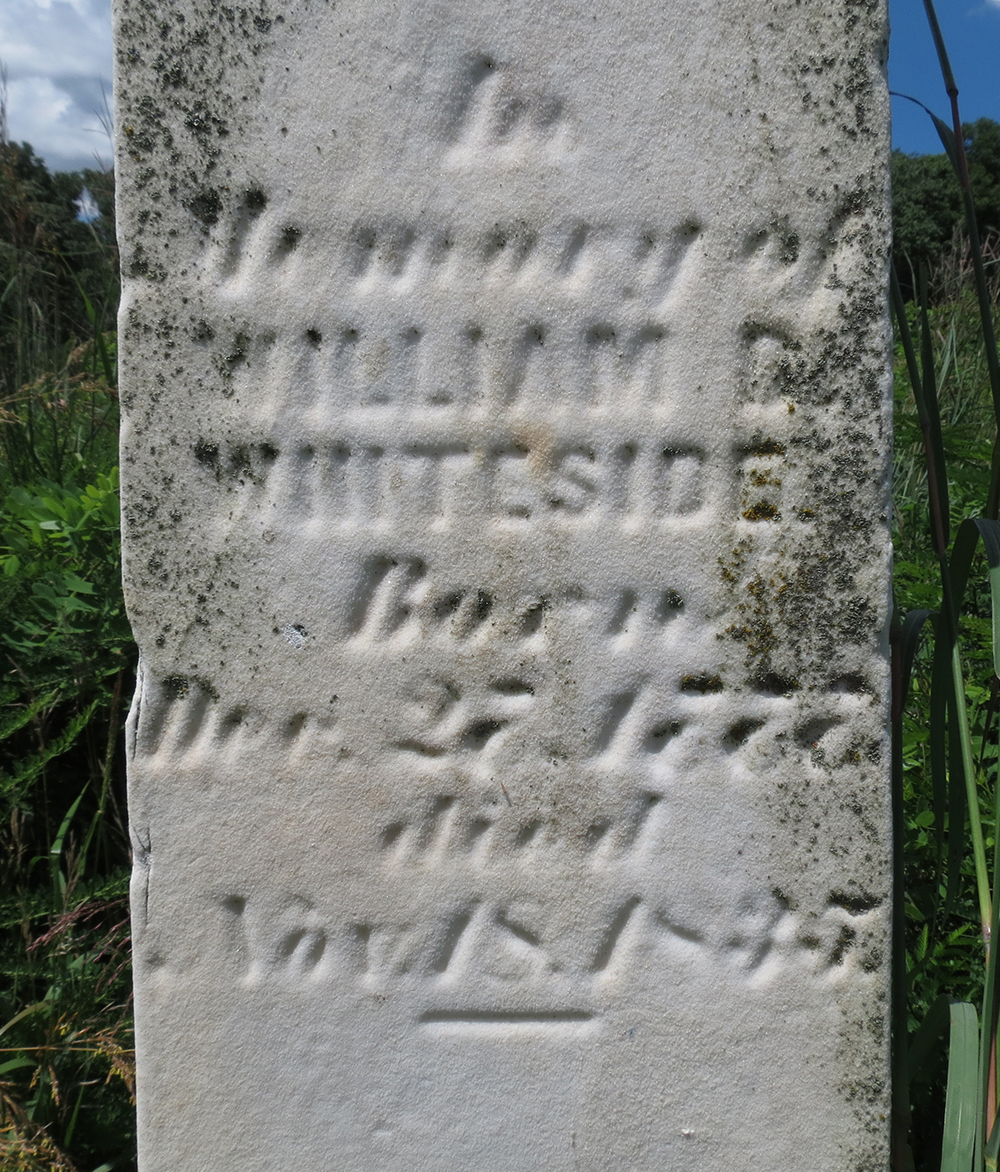

The last recorded activity of William B. Whiteside is a land deed he sold on September 6, 1833. His wife Sarah had died in July of 1833, and he died November 18, 1833. She was 54, he was 56.

There is some confusion regarding the exact dates of these deaths, though I am confident that these are correct. Though the dates are literally carved in stone on their obelisk grave, William B.’s death year contradicts other sources. The obelisk lists his death as occurring November 18, 1835, yet the Sangamo Journal first reported on his death in its January 4, 1834 issue. Though his obituary does not give a death date, it does state it occurred “a few weeks since,” indicating a death in late 1833.117 William Bolin’s probate papers from February 1834 state he died “on or about the 18th of November, 1833.”118 Both of these sources make a death year of 1835 impossible.

For reasons I discuss here, it is highly likely that the obelisk was not erected until 1867, by which time the family may have misremembered the exact birth or death dates of those who had died in the 1830s. We must therefore also be suspicious of Sarah Whiteside’s listed death date: July 30, 1833. The Sangamo Journal once again contradicts the grave, stating in an issue on August 17, 1833, “Mrs. Sarah R. consort of Major Wm. B. Whiteside, age 54" died the previous month on the 20th.119 Either way, Sarah died in July of 1833.

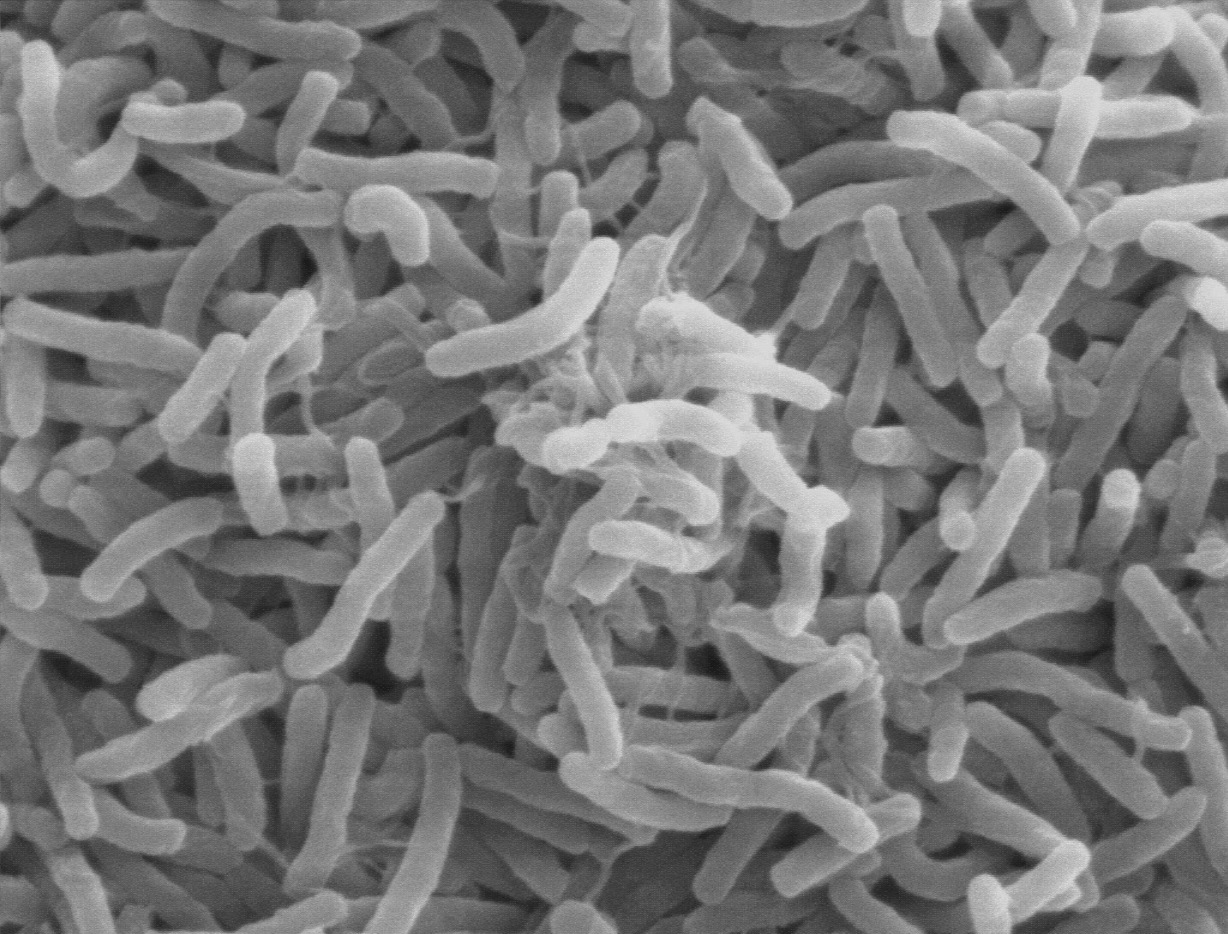

Less certain is the cause of death; however, some evidence suggests cholera killed both William and Sarah.

Cholera is spread through food and water contaminated with human feces containing the bacterium Vibrio cholera. As a result it is common in areas with poor sanitation, which was certainly the case for frontier Illinois. 80% of those infected with cholera do not develop symptoms, but the bacteria will be present in their feces for as long as ten days, further spreading the disease. Those who develop symptoms have acute diarrhea with varying severity, which leads to severe dehydration if left untreated. Without rehydration techniques of modern medicine, cholera can kill about half of those it infects.120

A massive outbreak of cholera began in 1832 in Illinois and claimed the lives of thousands.121 It is conventionally believed the disease was brought to the area by troops under the command of Winfield Scott in the Black Hawk War.122 The concurrence of the Black Hawk War and a cholera epidemic is no coincidence. With large groups of people from throughout the state and country converging in one area of poor sanitation made the barracks ripe for the spread of disease. As the troops went home, they then spread the disease throughout the state and nation. Anthropologist Anthony F. C. Wallace, who in 1970 called the Black Hawk War a disaster for both sides, considered the subsequent cholera epidemic one of the major consequences of the war, killing far more whites than actual bloodshed.123 Both the diseases of the American Civil War and the influenza outbreak after World War I are more famous examples of this phenomenon.