Though Anglo-American settlements had expanded between 1795 and 1810 and they felt more at home in the American Bottom, the tumultuous War of 1812 threatened all the progress they had made. Indian attacks coupled with one of the largest earthquakes in American history realienated settlers against nature. Achieving victory over the Indians and subsequently forcing them out of the state, Anglo-Americans were ready to fully tame the land after the war.

The semi-peace with Native Americans did not last. With support from the British, Indians resumed frequent raids against settlers in the American Bottom and other settlements in the south in 1810. Despite the improvements between 1795 and 1810, Reynolds still describes the settlements as “exposed” to Indian attack.1 Reynolds had been studying at college in Knoxville, Tennessee but became ill in 1810. He made his way back to the Goshen Settlement in the spring of 1811. On the way he saw very few people, as “Indians had alarmed the people on the road so much.” He also came across abandoned improvements along the Wabash River.2 All of the progress settlers had made in taming the wilderness was being undone.

Reynolds mentions a number of deaths in 1811 resulting from sudden Indian attacks. Near Shoal Creek in June, Indians killed a young man named Mr. Cox and “mangled his body cruelly,” and took his sister prisoner and stole some horses. A group of whites pursued and managed to rescue the girl and some of the horses. The same month a relative of the Whitesides, Mr. Price, was killed near the present-day location of Alton.3

Though Americans defended themselves into the war, Indian attacks continued to claim lives. In 1813 in present day Washington County, southwest of the American Bottom, two women were killed, “shockingly mutilated and cut to pieces,” and, most horrifyingly of all, a seven-year-old boy was “murdered: his entrails … taken out, his head cut off, and could not be found.”4 A handful of others were also killed through the course of the war, which were met with brutal retribution by white militiamen. It is difficult to know for certain how many civilians died, but undoubtedly the relatively sparse population meant even a handful of deaths sent shockwaves through communities.5

Reynolds aptly describes the feelings of the white settlers during the Indian attacks, “Although the country had its improvements, yet it was weak and defenceless. [sic] Numerous hordes of warlike and hostile savages surrounded the settlements, and indications were certain that they breathed a spirit of vengeance against the whites.”6

Once again whites felt encircled by a dangerous Indian landscape, and their fears only increased with two events that made Americans feel like nature had turned against them.

Though the educated Reynolds dismissed it as superstition, he describes the Great Comet of 1811, which appeared in the fall of 1811 in “the southwest section of the heavens,” and “believed by many to be a true harbinger of war, and stories were afloat amongst the people, that the roar of a battle, the reports of the cannon and small arms were heard in the skies.” This “added to the terrors of one class of people.”7

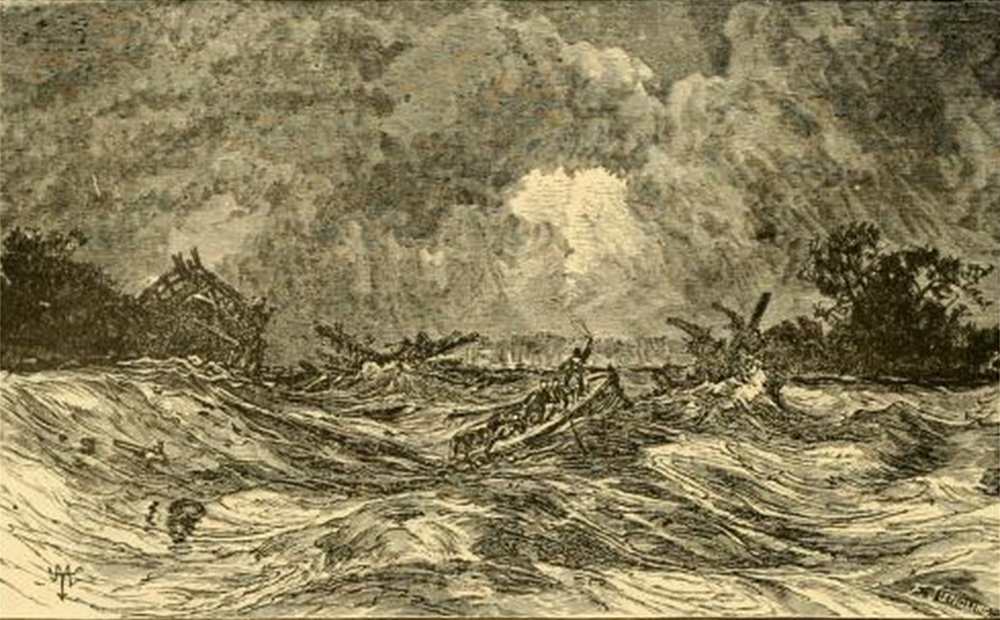

Yet the comet was topped by an even greater natural disaster that winter: the New Madrid earthquakes centered in the Mississippi Valley. They remain the most powerful earthquakes in recorded history to hit the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. The initial earthquake struck around 2 a.m. December 16, 1811, and had an approximate magnitude of 7.5, followed by a 7.0 aftershock the next morning, a 7.3 quake on January 23, a 7.5 quake on February 7, followed by hundreds of small shocks in 1813. In the American Bottom, chimneys were knocked over and whole log cabins collapsed. Near the epicenter in New Madrid, Missouri, the earth convulsed and sand and water were sprayed dozens of feet into the air in a process called liquefaction. The Mississippi itself formed into waves as the riverbed deformed. These waves moved backwards, making observers think the river was flowing upstream.8

Reynolds was at home in Goshen during the initial quakes. He writes:

On the night of the 16th November, 1811, an earthquake occurred, that produced great consternation amongst the people. The centre of the violence was near New Madrid, Missouri, but the whole valley of the Mississippi was violently agitated. Our family all were sleeping in a log cabin, and my father leaped out of bed crying aloud "the Indians are on the house." The battle of Tippecanoe had been recently fought, and it was supposed the Indians would attack the settlements. We laughed at the mistake of my father, but soon found out it was worse than Indians. Not one in the family knew at that time it was an earthquake. The next morning another shock made us acquainted with it, so we decided it was an earthquake. The cattle came running home bellowing with fear, and all animals were terribly alarmed on the occasion. Our house cracked and quivered, so we were fearful it would fall to the ground.

In the American Bottom many chimneys were thrown down, and the church bell in Cahokia sounded by the agitation of the building.9

His father’s first instinctual reaction to the earth’s convulsions was Indians attacking. Not only does this show how strongly they feared an Indian attack, it indicates how Anglo-Americans associated natural threats with Indians. With the settlers gearing for war with Indians and the British, the dramatic comet and earthquake must have produced a pandemonium among the people.

Yet Anglo-Americans remained firm against Indians and nature. Many fortified cabins into blockhouses or returned to the stations from the Indian wars of the 1780s and 1790s. Yet the population had quadrupled since then, requiring the construction of many new forts, including Fort Russel in Goshen. Settlers and livestock crowded together in stations and blockhouses.10 Reynolds’ house was “often filled at night with the citizens for fear of the Indians.”11

The return to the stations recreated the “inside and outside” relationship of the Arrival era, in which the interior of stations was secure and the outside landscape was dangerous and Indian. On February 7, 1812 about 20 militia officers of St. Clair County gathered at Cahokia to issue two petitions, both signed by a number of the Whitesides, including William B. One of the petitions states that Indians “are in an actual state of warfare with the U. States, and that the said frontier inhabitants is as much exposed to the hostile violence of these savages as any other part of the Union.” The petition goes on to call Indians a “numerous vindictive army of Bloodhounds,”12 further showing the association between Indian violence and a treacherous wilderness.

The “inside and outside” notion also be seen in Reynolds’ description of the security, or lack thereof, of the American settlements in Illinois:

[A] peep behind the curtain showed a weak and extended frontier from the site on the Mississippi where Alton now stands, down the river to the mouth of the Ohio, and up that stream and the Wabash to a point many miles above Vincennes, with a breadth of only a few miles at places. This exposed outside was three or four hundred miles long, and the interior and north inhabited by ten times as many hostile and enraged savages as there where whites in the country. The British garrisons on the north furnishing them with powder and lead and malicious counsels, and the United States leaving the country to its own defences [sic], presented a scene of distress that was oppressing.13

The federal government had not totally abandoned frontier Illinois. In 1811 Congress authorized the creation of 10 companies of mounted Rangers to protect settlers in the Northwest Territories. William Bolin Whiteside was appointed captain of one of four companies protecting Illinois. His cousin Samuel Whiteside was made captain of another company. All four captains were locals who drew up their own supplies and horses, with the incentive of protecting their home and family. Each company traveled between settlements patrolling for Indian war parties, both preventing attacks and pursuing Indians after they attacked.14

As a ranger, Whiteside had the opportunity to attack the root source of his alienation: the hostile Indians. He was finally able to exert revenge for the death of his younger brother. Traveling throughout the landscape, Whiteside and his fellow Indian fighters were determined to solve the Indian problem once and for all.

Yet the Rangers were not enough security for the Whitesides and other military officers. The second petition the militia officers issued to Illinois territorial governor Ninian Edwards lists their grievances caused by:

the many depredations committed by Indians, on our frontier Inhabitants, by stealing horses to a very considerable amount, plundering of other property, and by the massacre of many of the inhabitants… that it is also with pain we view the situation of our frontier to continue (as usual) unprotected and as much exposed as ever to Indian violence destitute of the common defence [sic] afforded it is the neighboring Territories by the parent Government… that we view with sorrow the breaking up of so many fine settlements on the frontier of this county by the peoples moving away to other parts of the Union occasioned by the [previously mentioned] distresses… it is the desire of this meeting that the Governor of this Territory do use his lawful means to establish the second Grade of Territorial Government, as it appears to us that by having a Delegate in Congress will much help the declining situation of our frontiers, and elevate our country one stride towards that greatness which the God of nature dictated.15

The military officers believed that the Illinois territory was not given as strong of a defense from the federal government as the other territories because, as a first grade territory, it did not have a representative in Congress, while a second grade territory would.16 With stronger political representation, the officers hoped that not only would the people of Illinois be protected from Indians, they would be closer to “that greatness which the God of nature dictated.” This greatness they refer to is a “civilized” and “improved” landscape, one defined by Anglo-American principles, not Indian savagery.

Anglo-Americans were once again alienated from the land during the War of 1812. All the progress they had made after 1795 was under threat from Indian violence, and they were forced back into the frontier stations for protection. Once again feeling surrounded and outnumbered by “ruthless savages,” their fears multiplied when the earth shook and some of their improvements came crashing down. Nothing was stable.

Yet Anglo-Americans held distinct advantages they did not have in the violence of the 1780s and 1790s. Their population was about 12,000 during the war as opposed to 1,000. With the federal government fully invested in a formal war with Great Britain, greater federal interest was paid to Illinois in the War of 1812. This time, the following peace with Native Americans would be permanent for the American Bottom. Illinois would only face Indian violence again in the brief Black Hawk War in the early 1830s.

All of the alienation Anglo-Americans had felt from the 1780s to 1814 impacted their views on nature. Though the land was beautiful, it was home to hostile Indians. The only way to obtain security was to “civilize” the landscape. Improvements were more than just for subsistence or to participate in the economy, they were a means for Anglo-Americans to exert control over the land away from the dangerous Indians. With the native threat finally removed with the war, it was time to fully transform the landscape to their design. To read about how their ideology changed after the War of 1812, see Statehood Ideology.

For how the War of 1812 served as a turning point in environmental impact, see War of 1812 Materialism.

1. John Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois (Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1887), 381.

2. John Reynolds, My own times: embracing also the history of my life (Belleville: B. H. Perryman and H. L. Davison, 1855), 122.

5. James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 150.

6. Reynolds, My own times, 123.

8. “New Madrid 1811-1812 Earthquakes,” United States Geological Survey, last modified April 18, 2014.

9. Note that Reynolds gets the date wrong, believing the initial earthquake happened a month earlier. Thus while Reynolds is useful as a source on the mindset and general history of frontier American Bottom, he can be less reliable for precise information. Reynolds, My own times, 125.

11. Reynolds, My own times, 123.

12. Clarence Edwin Carter, ed. The Territorial papers of the United States: Volume XVI, The Territory of Illinois 1809 - 1814. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1948), 189 - 190.

13. Emphasis in original. Reynolds, My own times, 130.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.