With new access to the Mississippi River and reduced Indian violence in 1795, the settlements in the American Bottom began a gradual expansion. With less threat of Indian attack, Anglo-Americans moved out from the security of the stations to establish farms throughout the region, slowly taming the wilderness. Their alienation continued to reduce as the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 further changed the Mississippi River from an international border with Spain to a shipping route. The American Bottom was no longer at the extreme western edge of the United States; it had become its relative center, with Lewis and Clark launching their expedition from the region.

Yet the transformation did not happen all at once nor did alienation completely disappear at the turning of the nineteenth century. The American Bottom remained largely isolated from the east, and Reynolds, having himself arrived in 1800, later described Illinois at the time as “a remote, weak and desolate colony. The population and improvements, increased slowly… The idea prevailed at that day, that Illinois was ‘a grave yard,’ which retarded its settlement.” Reynolds also mentions rampant diseases and that the inhabitants were “exposed” to Indian attack.1 Even with the Treaty of Greenville, settlers had not shaken the feeling of weakness against dangerous Indians, with Illinois considered a “grave yard” of Indian violence.

It did not help that many Indian groups continued to attack Anglo-Americans despite the treaty, particularly those that expanded north. In 1802, Reynold writes that the Pottawatomi chief Turkey Foot and his warriors committed a “bloodthirsty murder” of white settlers Alexander Dennis and John Vanmeter “at the foot of the bluff four miles southwest of present day Edwardsville.” Reynolds believes Turkey Foot’s party was conducting trade in Cahokia, and on their way back to their Indian settlements in northern Illinois saw that white settlements were spreading north. Reynold further includes racist speculation that the Indians were drunk as they supposedly often were when they traded in Cahokia. Reynolds describes the killing as “a wanton and barbarous murder of two good citizens in time of peace and without provocation,” but “not considered war, but a kind of Indian depredation.”2

Indian violence persisted alongside natural dangers. In both of his books Reynolds describes what he calls both a hurricane and a tornado, touching down in the American Bottom on June 5, 1805. This is his initial description of the tornado:

This tempest passed over the country about one o'clock, and the day before it was clear and pleasant. Persons who saw it informed me that it at first appeared a terrible large black column moving high in the air, and whirling round with great violence; as it approached, its size and the terrific roaring attending it increased. It appeared as if innumerable small birds were flying with it in the aft; but as it approached nearer, the supposed birds were limbs and branches of trees, propelled with the storm. As the tornado approached, it became darker; and in the passage of the tempest perfect and profound darkness prevailed, without any show of light whatever.3

The tornado “swept the water out of the Mississippi and lakes in the American Bottom, and scattered the fish in every direction on the dry land.” Worst of all, it laid waste to the settlers’ improvements, especially those of Dr. Carnes and his family. Reynolds writes:

The stock of the Doctor was all destroyed. A bull was raised high, in the air and dashed to pieces. A rail was run through a horse in his yard. The violence of the tornado was so great that it tore up the sills of the house in which the Doctor resided, and left not a stone on the ground where the stone chimney to the house had stood before the passage of the storm. The papers, books, and clothes of the Doctor were strewed for several miles around by the force of the tornado.4

Though the family survived, they had lost something incredibly important to them: the improvements they had made in an attempt to “civilize the wilderness.” Wilderness had struck back.

The persistence of unpredictable Indian and natural violence after the war meant William B. Whiteside continued wartime aggression even in peacetime. He, his brother Uel, and his father were all charged for the raid on the Osage settlement in 1795, for armistice had been declared that year. However, Governor Arthur St. Clair declared the attack justified, as the armistice had not become known. St. Clair was also aware that no local jury would indict them, with most sympathetic to Indian killing.5 Yet Whiteside continued to have legal problems in peacetime. On the morning of June 10, 1796, James Piggot claimed a number of “rioters” including some of the Whitesides broke into his station and carried away two free blacks.6 The Whitesides were not above taking what they wanted by force, even if it was illegal. William Bolin and other Whitesides were charged with horse stealing.7 In 1798, he and William Lot Whiteside were summoned to court regarding “trespasses, contempts, riots, assaults, and offenses of which they stand indicted.”8

Beyond demonstrating an occasional disregard for the law, these cases demonstrate the result of growing up on the violent frontier: a self-interested, and occasionally violent, independence. One would not get this image of frontiersmen from Reynolds, whose self-righteous teetotalism placed himself above such aggression. When this aggression was directed towards the land, the results were transformative.

Aggressive “improvement” of the landscape was easier during relative Indian peace. Reynolds describes the activities of William Bolin’s father following the treaty:

[He] turned his attention to his farm at the station, and improved it. He cultivated a fine apple-orchard, which, in days gone by, was quite celebrated, as very few orchards were in the country.9

While to modern observers a simple orchard might not be worth much celebration, to settlers the orchard represented the growth of the American Bottom settlements. “Improvements” like the orchard or other modifications Anlgo-Americans made to the landscape were how settlers made their own claim to the land, transforming it from an Indian, French, and natural landscape to an American one. “Improvements” not only “subdued the earth,” they increased settlers’ familiarity and identification with the land, a reaction against alienation. Reynolds describes the importance of improvements in glowing terms:

The great desideratum, something devoutly to be wished for, was the settlement and improvement of the country. This was the universal prayer of all 'classes of people in Illinois, to my own knowledge, for almost half-a-century. It was quite natural. The country was so thinly populated that the inhabitants did not enjoy the same blessings of the government, schools, and even the common comforts of life that were enjoyed by the people of the old states.10

Certainly many settlers wanted education, religious institutions, and other comforts. Yet they brought comfort not just from luxury, but also from familiarity. Settlers desired Anglo-American ways of life from the eastern states because they identified with them culturally. By transplanting Anglo-American civilization through improvements, settlers could further tame and identify with the landscape.

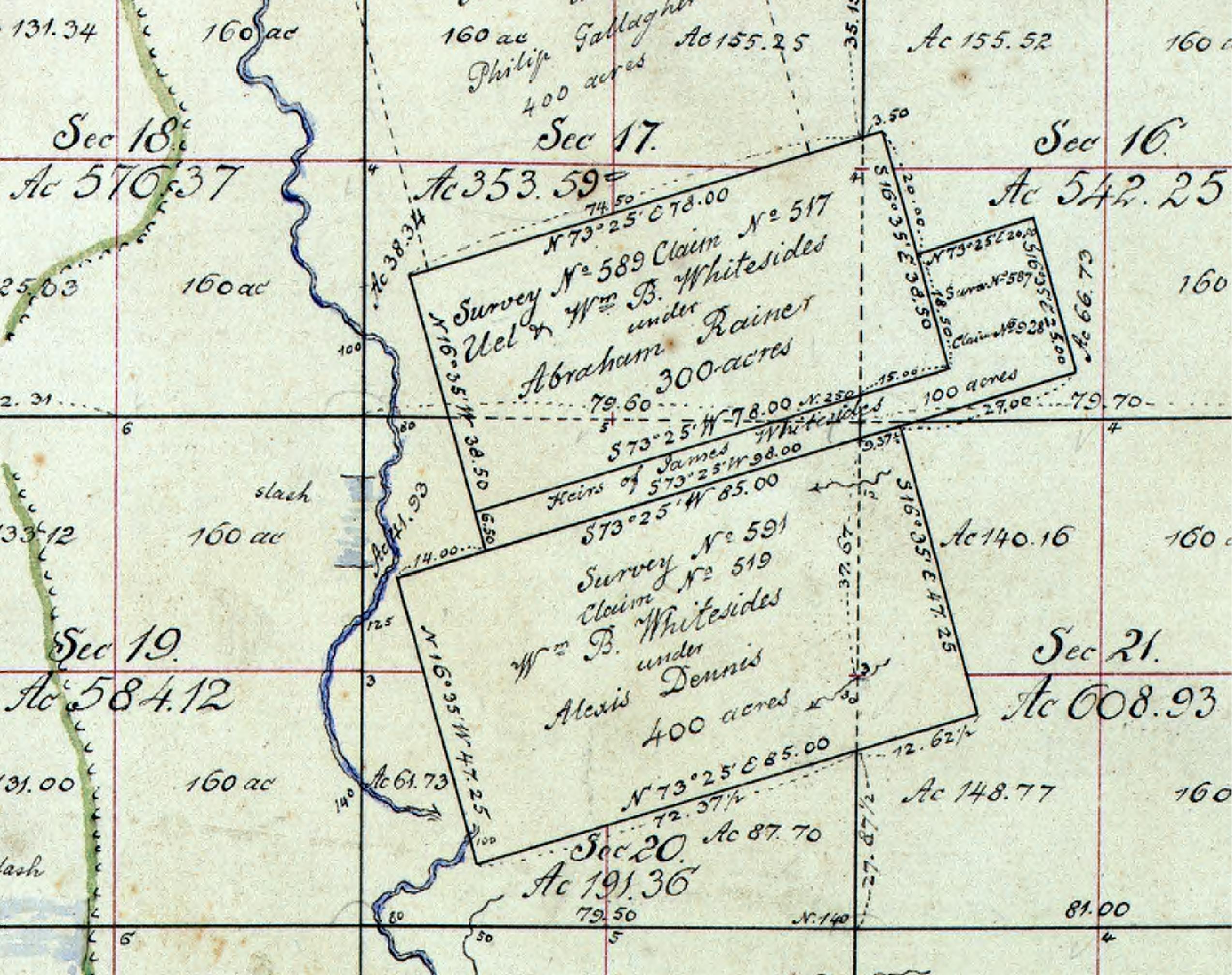

Reynolds wrote the preceding passage in the context of land titles, another dimension to improvements. For many land squatters who settled land before they officially owned it, land offices would grant them land ownership if they had improved it. This was how William B. and Uel Whiteside were granted their land in Goshen. On December 31, 1809, William Bolin’s southernmost claim in the Goshen Settlement was recommended for approval “on the ground of actual improvements having been made.” It was among 12 claims in present day Madison County recommended for approval by land commissioners. These commissioners defined these improvements as “not a mere marking or deadening of trees, but the actual raising of a crop, or crops, such, in their opinion, being a necessary proof of an intention to make a permanent establishment.”11

For Anglo-Americans then, improvements defined ownership, and therefore control of the land. Improvements were crucial to claim the land from Native Americans, the French, and nature itself.12

As Anglo-Americans eased their alienation through improvement, their feelings about the land began to change. This is visible in the naming of one of the new settlements formed in this era: Goshen. While the name initially shows signs of alienation, it also demonstrates an ownership of the landscape.

In 1799, three years before the death of Dennis and Vanmeter, a recently arrived Baptist preacher from Virginia explored the largely unsettled land north of Cahokia. Named David Badgley, he and his party surveyed the bluffs and named the area Goshen. This became the name of the settlement that developed in what would become Madison County.13 In 1802 a number of settlers moved north from the older settlements to the Goshen Settlement, including many of the Whitesides.14 Other prominent citizens migrated to Goshen as well, including Reynolds and his family in 1809. He recalled the natural beauty of the settlement in his youth:

When my father arrived in Goshen it was the most beautiful country that I ever saw. It had been settled only a few years, and the freshness and beauty of nature reigned over it to give it the sweetest charms. I have spent hours on the bluff, ranging my view up and down the American Bottom, as far as the eye could extend. The ledge of rocks at the present city of Alton, and the rocks near Cahokia, limited our view north and south; and all the intermediate country, extended before us. The prairie and timber were distinctly marked, and the Mississippi seen in places.15

This description reads very differently than his feelings while moving to Illinois. Now he is celebrating the “freshness” of nature because it had yet to be spoiled by settlement. Yet we must be careful to not read too much into this change, as both passages were written around the same time many years later. Still, Reynolds has a different memory of first arriving in unsettled Illinois compared to barely settled Goshen, which at least indicates that settlers remember feeling less alienated in the relative peace between 1795 and the War of 1812. This also indicates that seeking an unspoiled wilderness and feeling alienated were not mutually exclusive feelings. Settlers could feel both at different times, depending on how recently Indians had attacked or nature unleashed a calamity.

Reynolds also gives this description of the settlement:

It was, in truth, a land of promise, and some years after it was the largest and best settlement in Illinois. Goshen Settlement, so called in ancient times, embraced about all the territory of Madison County and was in its early life, as it always has been, a compact, prosperous, and happy community.16

Goshen’s greatest significance is in its name. Reynolds believes the name was given “on account of the fertility of the soil and consequent luxuriant growth of the grass and vegetation.”17 Yet this simplistic, Edenic explanation ignores the original meaning of the word Goshen, which is very revealing about settler mindset in frontier Illinois.

As a Baptist preacher, Rev. Badgley was certainly familiar with Goshen’s Biblical reference. In the Book of Genesis, Goshen features prominently in the narrative of Joseph, whose life connects the early patriarchs in Canaan to Moses’ liberation of the Israelites enslaved in Egypt. Because of a seven-year famine in Canaan, Joseph, who has gained favor with the Egyptian pharaoh, calls for his family to leave Canaan for Egypt, where food was still plenty. The pharaoh lets the Hebrews settle in the Land of Goshen in Egypt, located along the eastern Delta of the Nile. As described in the Bible:

And Pharaoh spake unto Joseph, saying, Thy father and thy brethren are come unto thee:

The land of Egypt is before thee; in the best of the land make thy father and brethren to dwell; in the land of Goshen let them dwell18

Though Goshen was supposedly the best land in Egypt, the Hebrews were in a foreign land and, following the death of Joseph, the Egyptians enslaved them. Thus Moses led them out of Egypt and to the Promised Land in the Book of Exodus.

Southern Illinois historian Jon Musgrave has written about the implications of this Biblical story on the naming of Goshen. He addresses the Edenic explanation of the name and writes, “If the land was so good, why not call it Canaan, the land the Bible describes as a land of milk and honey?” He goes on to argue that, just as the Israelites were foreigners in Egypt, Anglo-Americans felt like foreigners in frontier Illinois, both due to the presence of the French, Indians, and Spanish officials in Louisiana before 1803, as well as the American Bottom’s position at the extreme western edge of the United States. Americans thus identified with the Israelites as foreigners in an unfamiliar land. Though Goshen in both the Bible and Illinois was naturally beautiful and plentiful, their residents felt like they did not belong.19

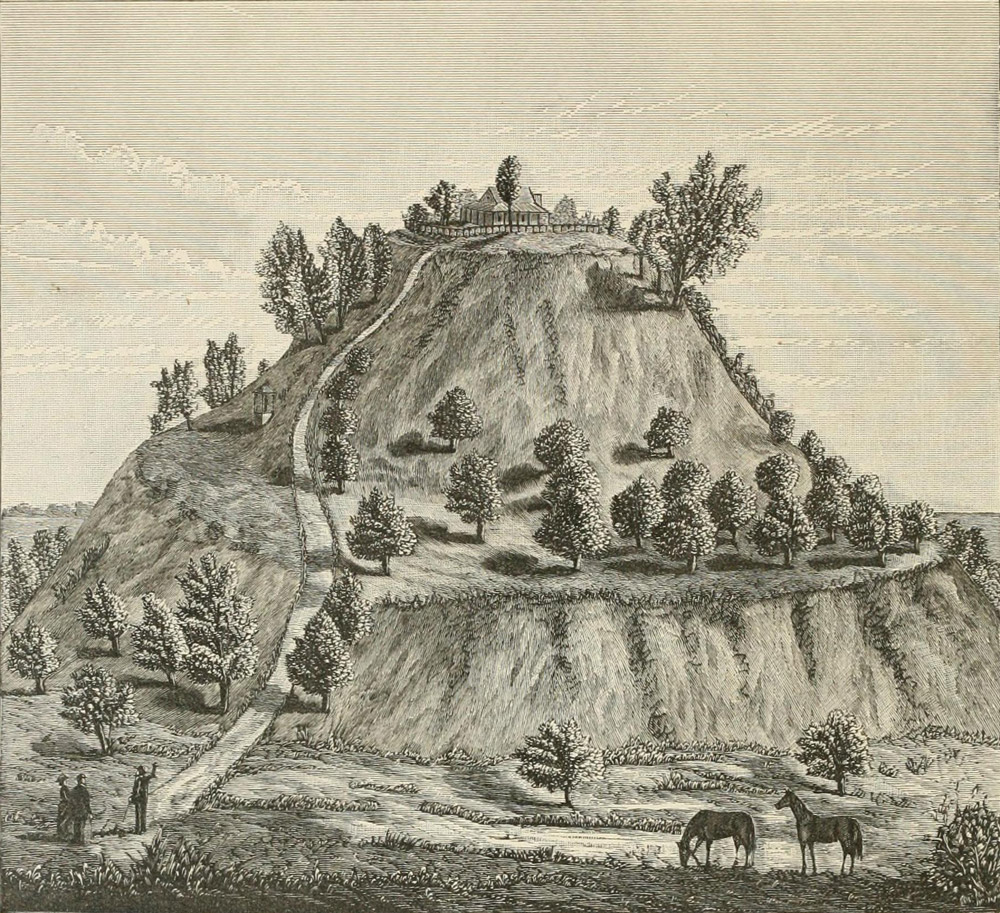

Yet, as Musgrave writes, “this part of Illinois was not just foreign, it was ancient, like Egypt itself.” Mounds and artifacts from the Mississippians scattered across the landscape, with ancient stone “forts” throughout southern Illinois. The mounds in particular resembled the Great Pyramids of Egypt.

Musgrave identifies a further association with Egypt: the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers with the Nile. Anglo-Americans had never seen rivers so massive and that flooded like the Nile. They likely recognized that the Mississippi watershed was the largest in North America, if not on Earth.20

The Goshen Settlement is not the only reference to Egypt in the region. To this day Southern Illinois is nicknamed “Little Egypt,” with a number of towns with Egyptian, Greek, and Middle Eastern names: Cairo, Metropolis, Thebes, Sparta, Lebanon, Palestine, Dongola, New Athens, Karnak, and, across the Ohio in Tennessee, Memphis. The mascot of Southern Illinois University Carbondale is the Saluki, a dog breed associated with the Fertile Crescent and ancient Egypt.

There are two conventional explanations of the name “Little Egypt:”

As Musgrave writes, however, both of these explanations come long after place names were established. Goshen was named in 1799; Cairo in 1818. While both theories help explain the popularity of the moniker, they fail to explain the individual place names.

Indeed, Reynolds occasionally uses language related to Jewish and Egyptian history. He describes the death of capitalist William Morrison in 1837 as “one of the great had fallen in Israel.”21 Describing William Bolin’s father as the patriarch of the Whitesides in Illinois, Reynolds writes, “They may look back at him with esteem and respect as the pioneer, Moses, that conducted them thro the wilderness to Illinois, the ‘promised land.’”22

William Bolin even named his oldest son Moses in 1804, two years after he moved to Goshen. Two of his other sons’ names show a nationalist pride. Ninian Edward Whiteside, born in 1814, was named after William Bolin’s commander in the War of 1812, Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards. His youngest son was given the name of America’s patriarch: George Washington Whiteside. He named his only other son after himself.23 That the name Moses would stand alongside names of Illinois and American pride shows the local association with the Exodus story.

The most intriguing part of Musgrave’s argument is the association between Egypt and Cahokia Mounds. Unfortunately Musgrave is not a particularly scholarly source and does not cite a source on this theory, so we must look at other sources to see how Americans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries understood the mounds.

The Mississippian Mounds scattered throughout the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys mystified early Americans, scholars and common settlers alike. Like the earlier French response to the Piasa Bird, many Americans could not accept that they were the works of the “savage” Native Americans. Various writers proposed a number of “white” civilized people, with proposals ranging from Egyptians, Phoenicians, Romans, one of the lost tribes of Israel, Vikings, Hindus, Celts, and, most wildly, survivors from the lost City of Atlantis. As Thomas S. Garlinghouse writes, “everyone seemed to have had a hand in mound construction except the Native Americans themselves.” In fairness, some scholars believed the Indians responsible, such as Thomas Jefferson, who conducted a scientific excavation of a mound on his property at Monticello. Jefferson was in the minority however, with many adhering to a “lost race” theory: that a white, civilized race was vanquished by the “red savages.”24

A number of settlers in Kentucky with less formal education than Jefferson adhered to a theory that a group of Welsh explorers came to America in 1170, settling along the Ohio River and building burial mounds. In this theory, they intermarried with local Indians and thus disappeared.25

Egyptians were among the most discussed group, especially given Monks Mound’s resemblance to the Great Pyramids of Giza. The mystery was still not resolved by 1882, in which the History of Madison County, Illinois, speculated on the civilized origins of Cahokia Mounds, and even calls them “the Egypt of America with its pyramids and tumuli looming up from the rich valley of the Mississippi in magnitude and grandeur rivaling in interest those of the Nile.”26

For his part, the college educated Reynolds was skeptical of a theory that the Romans had built a “fortification” near Marietta, Ohio. In his opinion it was “random shooting.” He however did not have any better ideas of their origin:

Above [St. Louis], and in almost every direction west of the river, as well as east, these Mounds are discovered in many places. I presume eternal darkness will rest on this subject, and hide from the search of inquiry all knowledge of the people who made these earthen pyramids.

Yet Reynold did associate the mounds with pyramids, strengthening the tie to the Egyptians.

Southern Illinois’ association with Egypt was one part of a larger movement in western culture in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: the Egyptian revival. Initially, Egypt was among many ancient, classical, or contemporary cultures that held European interest, including Greek, Chinese, and Roman. The western world became increasingly fascinated by ancient Egyptian culture after Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt between 1798 and 1801. America in particular adopted Egyptian iconography, seen in the reverse side of the national Great Seal and the obelisk of the Washington Monument. Americans of the early republic saw themselves as inheriting a long republican tradition stretching back through Britain, France, Rome, Greece, and ultimately Egypt, what they saw as the first civilization. Spreading westward, Americans hoped to discover an ancient past to North America, with many referring to the Mississippi as the “American Nile.”27

A belief in an ancient “white” civilization predating Native Americans can be seen in a religion developed in the early 19th century: Mormonism. The Book of Mormon tried to reconcile the lack of Biblical reference to Native Americans through its narrative that Lehi, an Israelite in Jerusalem, migrated to the Americas in 600 B.C. at the urging of God.28 Lehi’s decedents formed into two primary groups: the righteous and light-skinned Nephites and the wicked and dark-skinned Lamanites.29 After the visit of the resurrected Jesus Christ in 34 A.D., the Nephites became Christians, though the Lamanites eventually wiped them out after a series of wars 300 years later.30 Lamanites thus became the ancestors of Native Americans.31 Before the fall of the Nephites however, the Nephite Mormon wrote the history of the Nephites on a set of Gold Plates safely hidden away. Joseph Smith was then led to these plates by the angel Moroni in 1824, who then supposedly translated the plates into the Book of Mormon.32 Smith described the writing on the plates as being in “reformed Egyptian,”33 assuming the Nephites had learned Egyptian writing from their ancestors’ bondage in Israel. After writing the Book of Mormon, Smith purchased two Egyptian mummies that had arrived in New York from Paris.34

Needless to say, most scholars do not consider The Book of Mormon to be an accurate portrayal of the ancestry of Native Americans, but their beliefs are a window into the how early 19th century Americans conceived of pre-Columbian America. Smith and early Mormons arose out of the revivals of the Second Great Awakening in frontier New York. Mormonism is thus very much a religion born out of the beliefs of frontier America. They believed that North America was once home to a white, civilized, Christian people that were slaughtered by Native Americans. Through the angel Moroni and Joseph Smith, early Mormons believed it was their duty to maintain the traditions of the Nephites, making them the rightful inheritors of the land.

Though Anglo-Americans in the American Bottom were less in danger from Indian attack between 1795 and 1810 and had begun to dominate the land through agriculture, they retained lasting scars from pre-1795 warfare and still felt insecure from the unfamiliar wilderness. Particularly puzzling were the mounds and other ruins of the Cahokians, for which Americans began to develop an explanation, as seen in the naming of Goshen. Their resemblance to the pyramids of Giza and the proximity to the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers reminded settlers of Egypt. In naming Goshen, Rev. Badgley evoked the feeling of isolation the Israelites felt in Egypt and not an Edenic paradise. In Eden, everything Adam and Eve need are given to them. In Goshen, the Israelites must toil in the hopes of eventually reaching the “promised land.”

Associating the mounds with Egypt had further implications. By appropriating Cahokia Mounds into their own “white civilized” cultural history, Anglo-Americans began to ease their alienation. In their minds, the mounds were not the works of the “ruthless savages” that slaughtered their friends and family or their ancestors. They were the works of their own cultural ancestors, whether they were Egyptian, Hebrew, or Nephite. Whites were thus the proper, civilized inheritors to the land, justifying the removal of the Native Americans who, many believed, killed the white builders of the mounds. After all, when Reynolds tries to justify Native dispossession, he writes, “It is quite possible, that these same tribes drove off the peaceable occupants of the country, and then took possession of it by force, as we have done.”35

Yet alienation would soon return in full force with the War of 1812. To see how ideology changed during the war, see War of 1812 Ideology.

To read the precise details of environmental impact in this era, see Goshen Materialism.

1. John Reynolds, My own times: embracing also the history of my life (Belleville: B. H. Perryman and H. L. Davison, 1855), 72.

2. Reynolds, My own times, 74; John Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois (Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1887), 280.

3. Reynolds, My own times, 168 - 169.

5. Carl R. Baldwin, Echoes of Their Voices, (St. Louis: Hawthorn Publishing Company, 1978), 278.

6. St. Clair County Index to Court Records Defendants 1790 - 1850, Case #517. Part of the Whiteside genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

7. St. Clair County Illinois Case No. 597. Part of the Whiteside genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

8. St. Clair Co. Circuit Court Case # 782. Part of the Whiteside genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

9. Jay Gitlin, The bourgeois frontier: French towns, French traders, and American expansion. (New Haven : Yale University Press, 2010), 15.

10. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois,189.

12. “Chapter VII: Pioneer Settlements,” in History of Madison County, Illinois, Illustrated, With Biographical Sketches of Many Prominent Men and Pioneers, (Edwardsville: W. R. Brink & Co., 1882), 67.

13. For how land ownership and improvements impacted economics and ecology, see Statehood Materialism.

14. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 280.

16. Reynolds, My own times, 102.

17. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 280

19. Gn 47:5-6 KJV. The Joseph narrative begins in Genesis 37 and ends in Genesis 50.

20. Jon Musgrave, “Welcome to New Egypt!,” American Weekend. (1996).

21. Ibid.

22. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 165.

24. William R. Whiteside, “The Family of William Bolin Whiteside” (unpublished manuscript), part of genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

25. Thomas S. Garlinghouse, “Revisiting the Mound-Builder Controversy,” History Today 51, no. 9 (2001): 38.

26. Elizabeth A. Perkins, Border Life Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 72.

27. William McAdams, “Chapter V: Antiquities,” in History of Madison County, Illinois, Illustrated, With Biographical Sketches of Many Prominent Men and Pioneers, (Edwardsville: W. R. Brink & Co., 1882), 58.

28. Richard G Carrott, The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning; 1808-1858. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 2 and 47 - 49.

29. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “The Book of Mormon.” (accessed March 20, 2016).

30. 2 Ne 5:21, The Book of Mormon.

31. Morm 8:3, The Book of Mormon.

32. Even recently the LDS church has considered Lamanites to be one of the ancestors of Native Americans, though the church has issued a statement that, “Nothing in the Book of Mormon precludes migration into the Americas by peoples of Asiatic origin.” See The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “Introduction to the Book of Mormon.” (accessed March 20, 2016); The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “DNA and the Book of Mormon.” Issued November 11, 2003.

33. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “The Book of Mormon.” (accessed March 20, 2016).

34. Morm 9:32, The Book of Mormon.

35. Carrott, 48.

36. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 23.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.