This site is a study of the life, landscape, and environmental impact of William Bolin Whiteside — one of the first Anglo-American settlers to live on the land that became the campus of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

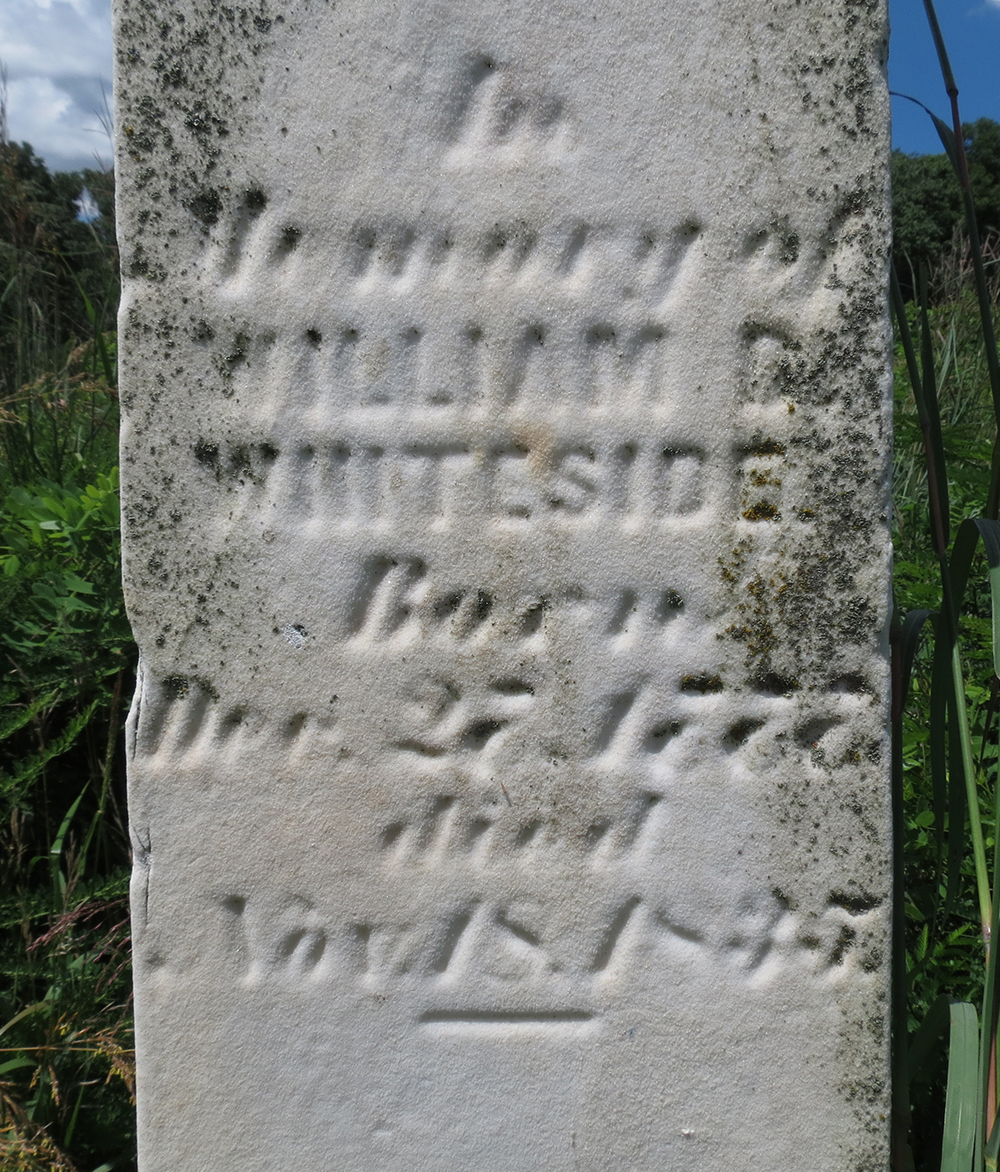

Whiteside died in 1833, so the only remaining marks he leaves on the landscape are a white obelisk grave he and his family are buried under, as well as the adjacent road bearing his name that was constructed in 1980.1 All the grave explicitly tells us are the names of his wife and two daughters: Sarah Raines Whiteside, Sarah Swigert, and Elizabeth Claypoole, as well as the dates of their births and deaths, which for William Bolin were December 24, 1777 to November 18, 1833.2

Whiteside seems lost to history. He died a mere five years before the first known photograph of people,3 and did not live in a time or place that allowed his portrait to be taken. Beyond appearance, the Illinois frontier has left behind scant written records, and Whiteside himself only produced a handful of written documents that survive to today.

What we do know about William B. Whiteside is largely based on genealogical research by his and other Whiteside descendants. For an overview of what we know about his life, see Biography.

If William Bolin Whiteside is so enigmatic, then some might question the validity of studying him at all. History has to have a basis in primary sources to make any sort of claim, making it difficult to form arguments based on Whiteside. Historians interested in a case study of an Illinois frontiersman might seem to be better off studying a prolific contemporary of Whiteside, Illinois governor John Reynolds.

Yet Reynolds can hardly be considered a typical man of the Illinois frontier. He went to college and was a prominent politician of the state, serving not only as governor, but also in the United States House of Representatives and the Illinois Supreme Court.4 Whiteside is far more an “ordinary” frontiersman, who as Reynolds tells us, did not receive much formal education.5 He fought far more Native Americans than Reynolds ever did, who only served as a private in the War of 1812. Whiteside also owned enslaved African Americans, a major point of contention in the early formation of Illinois.6 Whiteside thus serves as a case study of a number of issues at stake in frontier Illinois, including the early pioneers’ relationship with nature. In addition, because of the genealogical work of former SIUE professor William R. Whiteside and other Whiteside descendants, we know more about the Whitesides than other members of the Illinois frontier that did not go on to become major politicians.

Any historian since the social history movement of the late 20th century would recognize the value of studying a man like Whiteside over Reynolds. According to the assumptions of social history, Whiteside and ordinary settlers like him were the primary historical actors in frontier Illinois, not just political leaders like Reynolds. Of course, frontier Illinois was not just home to white males like Whiteside. Also affecting historical change were white women, Native American men and women, enslaved African-American men and women, and, yes, political leaders like Reynolds. Whites were not a homogenous group either, with both Creole or French people and mixed Métis, a mix of French and Native American.

My study seeks to restore the agency of Native Americans in frontier Illinois history and discusses the French, but it does not directly engage with women’s role on the frontier or enslaved African-Americans. Though I do not address these issues, Whiteside can be examined from an angle of gender or black history. He had a wife, Sarah Raines, and multiple daughters, some of whom were divorced and remarried. Divorce on the frontier is a rich topic. Though I discuss masculinity and its relation to nature, femininity on the frontier is also worth exploring. Whiteside also owned enslaved blacks, resulting in significant questions about how slavery persisted in a supposedly free territory and state. My hope is that future SIUE students study these issues.

My narrative does focus on groups frequently ignored by traditional history: nonhuman animals, plants, and other parts of nature. Social history need not limit itself to just human historical actors; other living ' things have had a profound impact on history. One need merely look at the Black Plague or the smallpox epidemics that ravaged Indians throughout North America for examples. As my argument reveals, pigs and cows had a significant impact on the environment and Anglo-American society in frontier Illinois.7

Yet even though a white male, Whiteside and fellow Anglo-American settlers of frontier Illinois are not frequently studied. Likely the most frequently studied group in the early history of the St. Louis region are the Mississippians of Cahokia Mounds, which is well deserved as the largest pre-Columbian population center north of the Rio Grande. The colonial French are also given limited attention. The majority of scholarship in early American history focuses on the 13 colonies; only recently has attention expanded to the frontiers in places such as west Florida and Kentucky. Near St. Louis though, a scholarship gap has emerged between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Though the American Bottom, the frontier name for the St. Louis Metro East, was the first region settled by Americans in Illinois, I have yet to find any frontier scholarship on the region. Frontier studies in Illinois have either focused on the whole state or regions settled after the 1810s.8

Historians have not ignored early frontier Illinois entirely due to lack of interest. There are limited written documents from Illinois before the 1820s, and those that exist are scattered in multiple archives.9 Whiteside genealogists dedicated to finding scraps of information about the Whitesides have made a study of the American Bottom easier. Thus I will be using the Whitesides and William Bolin in particular as a case study for how Anglo-American settlers related to and modified the landscape of frontier Illinois between their first arrival in 1779 to around William Bolin’s death in the 1830s.

However knowledge of the Whitesides is limited, so to a certain extent I will rely on what we generally know about Anglo-American settlers and see how what we know about the Whitesides fits into that established narrative.

It is first important to precisely explain the time, place, and group I am studying: the Anglo-American settlers of the American Bottom between their first arrival in 1779 to the 1830s. They were not the first Euro-Americans to settle Illinois; before them were the French and before the French were Native Americans. Most of the first Anglo-American settlers in the American Bottom came from the south; specifically Virginia, Maryland, the Carolinas, and Kentucky. I will discuss these three settlement groups at greater length later on.

The American Bottom is the name for the Mississippi bottomlands on the Illinois side of the Mississippi near St. Louis; today part of the Metro East. They run from Kaskaskia in the south to Alton in the north. William Bolin Whiteside’s land was located in the Goshen settlement in the northern region of the American Bottom along the bluffs, the western part of modern day Edwardsville.

The fourth governor of Illinois, John Reynolds, serves today as one of the most prominent primary sources on frontier Illinois. His family moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1800 when he was 12 and later moved to the young Goshen settlement in 1807. Writing in 1855, he describes a number of the animals that once lived in southern Illinois that were either gone or in reduced numbers by the 1850s. He writes, “In 1800, and many years thereafter, game, deer, bear, and elk were plenty in Illinois... In the swamps of the rivers were great numbers of musk rats.” He also mentions raccoons, beaver, otter, elk, and bison. Reynolds was also amazed at bird migrations up and down the Mississippi Valley in the fall and spring, with so many birds that, “at times the air was almost darkened with them.” He particularly adored the swans, writing “the notes of their music, sung on their passage were noble and majestic.11

Yet Reynolds could no longer enjoy the swans’ song, for, as he writes, “almost all these fowls, like the animals of the chase, cease to exist in Illinois.” Reynolds correlates the loss of animal species with the end of the frontier era and removal of Native Americans, writing, “The game, the fowls, Indians and pioneers all seem to sink below the horizon about the same time.”12 In another book, he writes, “The increase of the population in Illinois diminished the wild game,v and “[Wild fowls], like the Indians, have almost entirely disappeared on the approach of the white population.”13 Without getting into the complexities of Reynolds’ explanation right now, his overall point is rather simple: the arrival of white settlers brought these animal extinctions. Disappearing species was not the only change they brought either. As Reynolds states, “The vegetation – particularly the grass – grew much stronger and higher fifty years ago than it does at this time. Corn does not grow as large or yield as much per acre as it did in these olden times. This is the opinion of almost all the pioneers : that the vegetation is not so luxuriant and stout as in former days.”14 Bears and bison were replaced with pigs and cattle.15 Most dramatically, demand for wood deforested much of the Mississippi Valley in the St. Louis region, altering the Mississippi’s watershed and causing the river to drastically change course in the mid-nineteenth century, which in turn destroyed many colonial French towns in Illinois.16

Southern Illinois was not the only place in America to experience dramatic environmental changes after the arrival of white settlers. This pattern has repeated throughout the settlement of the United States as European colonialism pushed further into the Americas. Historian William Cronon studied this phenomenon in colonial New England, and wrote this about the suggestion that white settlement caused the environmental changes, “In a crude sense, there can be little doubt that this was true,” yet “[o]ne serious danger of a two-point analysis which contrasts New England before and after the Europeans is that it obscures the actual processes of ecological and economic change. It makes the change seem too sudden and unicausal.”17 In addition, to reduce ecological changes to a simple equation of “white arrival = ecological degradation” both makes the process inevitable and suggests that it is in the nature of white settlers to subdue nature. Reynolds even implies that it was the “instinct” of birds to migrate away upon the arrival of white settlers.18 My goal is thus to provide a more complex explanation for why Anglo-American arrival resulted in dramatic environmental change. What did the settlers do that resulted in these changes? Why did they do them?

My explanation for the Illinois environmental changes rests on two parallel points: an ideological and cultural argument and an economic and materialist argument. The former concerns how Whiteside and his contemporaries felt about the natural landscape they inhabited, and the latter explains how the subsistence strategies introduced by settlers impacted the environment.

My cultural thesis is that, initially, Whiteside and other settlers improved the land not only to access basic necessities, but also to alleviate a feeling of alienation from a dangerous, native wilderness. Thus they “tamed” this wilderness through improvements, which allowed them to identify with their property. This alienation largely stemmed from unease over unfamiliar French and Native American culture, which heightened as warfare broke out between Indians and Americans. As whites pushed Native Americans further west their influence did not vanish, even though they no longer had “in-person” contact. The white settlers of southern Illinois increasingly came to identify their local culture with Egypt, an association rooted in Native American influences.

As for the materialist thesis, I will be describing in detail what precise actions the settlers did and how those actions had an ecological impact. Much of this was not only dictated by their attitudes towards nature of my first thesis, it was also driven by economic forces. The new subsistence patterns and lack of mobility of the Anglo-Americans was coupled with a growing market economy, with connections to eastern states and the growing global, capitalist economy. These forces dictated a relationship with nature far different than those of the Native Americans.

Generally, any narrative of the American frontier can be placed into one of two categories: one that laments the fall of Native American presence, and the other that proclaims the rise of an Anglo-American society that became more and more civilized. My two theses fit into each category respectively. The two theses are not strictly parallel; they do meet at certain points. In one sense they have an inverse temporal relationship: as alienation decreases over time, the market economy increases.

Well-documented are the beliefs of eastern elites like Thomas Jefferson and J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur about the unlimited potential of the unspoiled American West - that America could escape the tyranny of Europe through developing a seemingly endless expanse of Democratic, classless agrarianism that would last hundreds of years.16 Less studied are the frontier farmers themselves that Jefferson and others so celebrated, likely because of the scarcity of written evidence from the frontier. Historians have recently begun a renewed interest in frontier studies as part of the new social history.20 Yet frontier Illinois has yet to receive significant scholarly attention, with a few exceptions. Here I will discuss three of them and how they discuss the American settlers’ relationship to nature.

The first social historian to write about the Illinois frontier was John Faragher in Sugar Creek: Life on the Illinois Prairie (1986). Writing a social history of the Sangamon County settlement near modern-day Springfield, Faragher pays a great deal of attention to landscape, writing “an important dimension of local community is landscape.”21 His interpretation of how settlers viewed landscape is essentially pastoral, with much celebration of the improvements settlers had made. He bases this interpretation on what a handful of settlers wrote. For instance, Moses Wadsworth, who in 1840 came to Sangamo at the age of 14, described the improvements in his 1880s memoirs with some nostalgic pride, and that men and women “sent back enthusiastic accounts of the country to the friends they had left behind. Their attractive representations brought others, and ‘the San-gam-ma country’ came to be known as the farmers’ paradise.”22 Faragher also mentions that Reynolds mistranslated Sangamon as “the country where there is plenty to eat,” when in fact the Algonquian term actually meant “river’s mouth.” Faragher interprets this mistranslation as “unintentionally captur[ing] something of the ‘improvements’ that Americans introduced into central Illinois.”23

Faragher is especially useful in showing the pride and importance of improvements to settlers. Yet, he is limited by the available sources to be able to come to a definitive conclusion regarding frontier attitudes towards landscape. Certainly he is able to get a useful number of details about the form of the landscape, but in terms of the actual perspective of settlers, his argument is lacking. Aside from Wadsworth, who arrived in Sugar Creek decades after it was first settled, his interpretation is based on Reynolds’ mistranslation, a hymn by Samuel Stenett, and the views of George Washington on the Ohio country. Thus, Reynolds is unable to completely get out from the elite, Edenic view of landscape.

In 2000, Douglas K. Meyer’s Making the Heartland Quilt: A Geographical History of Settlement and Migration in Early-Nineteenth-Century Illinois provided a more quantitative interpretation of the settlement of Illinois, yet Meyer also examined what he called “image builders,” writers of guidebooks urging settlement in Illinois. One of the most prominent of these is John Mason Peck, a Baptist minister born in Connecticut who moved to St. Clair County, Illinois in 1822 and emerged as a prominent citizen of the state.24 His influence remains at SIUE today in the naming of its first classroom building: Peck Hall. In order to encourage settlement in Illinois, Peck published three gazetteers: A Guide for Emigrants (1831), A New Guide for Emigrants to the West (1836), and A Gazetteer of Illinois (1837). As Meyer describes it, Peck built an image of an ideal Illinois by “employ[ing] Edenic, visual descriptors of hope, ‘beautiful groves of timber, and rich, undulating, and dry prairies’” and so on, often repeating phrases for different counties, “some of the finest lands in the state are in this county … one of the best inland agricultural counties in the state … one of the finest agricultural districts in the United States.”25 Thus, Meyer’s interpretation relies on how such glowing descriptions attracted settlers to the United States.

Yet while Peck’s glowing language might have caught the interest of future settlers, we must be careful not to ascribe such beliefs to people already in Illinois, especially to settlers of Whiteside’s generation who were active in Illinois decades prior to Peck’s arrival in 1822. It is crucial to remember that Peck was essentially writing as a salesman, whose product was an Edenic image of Illinois. As with any salesman, his interest is to make the product as appealing as possible to a particular audience. Thus, Meyer’s interpretation of Peck is not necessarily reflective of how Illinoisans felt about their environment, but it helps illuminate the natural ideal settlers strove for.

One final recent work on the Illinois frontier is James E. Davis’ Frontier Illinois (1998). His book is useful for a narrative account of Illinois settlement and for details on the ways American settlement impacted the environment. While largely focused on exposition rather than interpretation, Davis still makes arguments based on primary sources. One of the most major themes of his work is the tranquility of frontier Illinois. As he puts it, “Settlers and visitors – people on the scene – rarely wrote about conflict, violence, and homicide.” He then reveals that only one murder occurred in northern frontier Illinois from June 1849 to June 1850.26 Yet even the authors of Davis’ preface acknowledge that violence was only absent in Illinois after the Black Hawk War of 1832.27 To claim that frontier Illinois was peaceful requires this caveat, for otherwise we would have to ignore the Black Hawk War, the War of 1812 in Illinois, and Indian warfare in the 1780s and 1790s, which, with the possible exception of Indian wars upon French arrival, were likely the most violent episodes in Illinois history after European contact.

Ultimately, the flaw with these three scholars is that they focus too strongly on the Illinois frontier after the Black Hawk War, especially when it comes to Ango-American views of nature. Meyer and Faragher’s interpretations are not wrong per se – they are representative of how many Illinoisans felt about their natural landscape after the 1830s, and likely Davis is correct that Illinois was largely peaceful after 1832. Yet by then Americans had been in Illinois for more than 50 years, and neither Meyer nor Faragher looks at documents regarding landscape from before the 1830s. This is particularly flawed because Native Americans were largely gone from Illinois by then, removing them entirely from how settlers felt about nature. My hypothesis seeks to restore Native American agency in the mindset of American settlers.

Reynolds is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Illinois frontier from before the War of 1812, making him an invaluable source. However, like any source his writing is problematic.

Though I discussed earlier how Reynolds, as the educated governor, does not represent the experiences of most Anglo-Americans in frontier Illinois, he still gained an “everyday” experience of the Illinois frontier as a child. His family moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1800 when he was 12 and later moved to the young Goshen settlement in 1807, five years after William Bolin Whiteside and his family relocated to Goshen. Reynolds first went to college in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1809 at the suggestion of his uncle who lived there, altering the course of his life away from farming and towards law and politics.28 Before this event though, his experiences were not dissimilar from that of Whiteside, especially given their geographic proximity in Goshen. Many of the frontier experiences of alienation from the land had a lasting impact on young Reynolds.

While undoubtedly among the most elite of the citizens of early Illinois, Reynolds was not entirely dissimilar from the Whitesides. William Bolin and many of his male relatives were also prominent citizens. His brother John served as the Illinois treasurer,29 and his cousin Samuel was the first representative of Madison County in the Illinois legislature, later serving as the namesake of Whiteside County.30 William Bolin himself served as sheriff of Madison County.31 With so few white males on the frontier, it was inevitable that many if not most became part of the political or social elite.

Yet another issue with Reynolds as a source is that he writes half a century after the events occurred. We cannot assume that his recollections of his childhood were necessarily how settlers understood their relationship with nature at the time. The most effective solution to these problems is to use Reynolds alongside other primary sources written as the events unfolded, such as a handful of petitions signed by the Whitesides regarding Indian violence.

My ideological thesis is largely based on Elizabeth A. Perkins’ study of the frontier of the Ohio River Valley in Border Life: Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley (1998), which reaches the unique perspective of settlers. She overcame the paucity of written evidence through the ethnographic work of the Reverend John Dabney Shane, who conducted oral interviews of surviving frontier men and women in the 1840s. Unlike most works of history from his time, Shane’s work was interested in everyday life on the frontier, providing a rare window into the perspective of the common settler. Though she studies a slightly different time and place, southern Ohio and Kentucky in the Revolutionary War era, Perkins still proves a key resource. Whiteside and many other early Illinois settlers came from the Kentucky frontier, descending from the cultural lifestyle Perkins studies. In her chapter on landscape, Perkins argues that there were two conflicting notions of American landscape in the late 18th and early 19th centuries: the Edenic, unspoiled wilderness view held by metropolitan outsiders both to the east and in the future, and that of the settlers themselves who initially saw the landscape as threatening and needing to be tamed.32

If Perkins is limited at all, she does not fully explore the significance of her conclusion, possibly because she does not focus solely on landscape or ecology. She writes not in response to Edenic arguments of Faragher and Meyer, but rather to what she calls the tendency of frontier history in general to oversimplify into a Turnerian progress narrative.33 My intention is to take her conclusions about settlers’ relationship to landscape and explore how this relationship plays out in the ways they modified their environment.

I have already referenced the work of William Cronon a number of times; he is a prominent environmental historian in the United States. Cronon has written extensively about Illinois in the nineteenth century in Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991), which examines the relationship between Chicago and Midwestern agriculture. He argues that capitalism through Chicago transformed the landscape of the Midwest, as the countryside shipped agricultural products to Chicago to be traded throughout the world. Unfortunately, this is the end result of my argument, as Chicago did not begin its meteoric rise until shortly after Whiteside’s death. Over a few pages, Cronon discusses Midwestern agriculture before Chicago, which I utilize alongside a few other sources.34

Of far greater use to me is Cronon’s earlier and possibly most famous work: Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (1983). Unlike Nature’s Metropolis, Changes in the Land is concerned primarily with pre-industrial activities of colonists and Indians in New England, such as the fur trade, logging, and agriculture, though capitalism was still the impetus for many of the changes. I can thus use Changes in the Land as a guide for how initial colonization transformed the ecology of North America.

Cronon’s study is invaluable, but not without challenges, as his study differs from mine in a number of respects. Most obviously, his study examines a different place, colonial New England, with somewhat different ecology and geography than the American Bottom, with settlers acting in a different historical context. His time frame is also wider, stretching from 1600 to 1800, giving much more time for ecological changes. Yet his study is a strong example of the impact Anglo-American settlement had on the environment. Keeping this in mind, I will be looking at the actions of New Englanders and the resulting environmental impact, then seeing if Americans in Illinois had similar activities.

My website has two suggested ways to read: chronologically or by thesis. I have divided my study period into four eras: Arrival (1778 - 1795), Goshen Settlement (1796 - 1810), War of 1812 (1811 - 1814), and Statehood (1815 - 1833). Each section has a page for the two theses: ideology and materialism. Readers can read both pages in each era in order, the chronological format. The thesis format, on the other hand, presents the two theses independently of each other in chronological order.

Each format has its own advantages. Chronological order better shows the relationship between alienation and a desire to connect to a market economy, as well as the consequences of settler ideology about nature. Other readers though might find it easier to read through each argument separately.

In addition to the main argument, I will also include several background information pages I intend to be read before the main argument: an overview of the Illinois frontier settlement, a biography of Whiteside, and the settlers of Illinois before the Anglo-Americans. Readers already familiar with the Illinois frontier can choose to skip over that section, for example. Returning readers can also go back to particular sections as they wish.

For the presentation of my two arguments, I will be taking advantage of two aspects of web writing: nonlinearity and leaving a degree of interpretation up to readers, both of which are more difficult to convey through traditional, linear arguments such as essays or books. Though readers of print media are free to read any portion of the argument in any order, the intended process of reading is generally thought of in basic terms: from beginning to end. Yet in practice this is often not the case. Whether fiction or nonfiction, readers often skip to the end to see where the narrative or argument is headed. Even if initially they read completely in order, many later return to specific passages. Often rushed college students or scholars only interested in a superficial reading may only skim and read the intro and conclusion. Web writing only further supports this form of reading.

Though this website is not be strictly linear, it is not technically nonlinear. Nonlinear implies that there will be no order or progression of argument. History is often the study of change over time, which is impossible to discuss without some order. My study too involves change. A more appropriate term for my website is multilinear: giving multiple paths for reading. Likely the most well-known print example of a multilinear narrative is Choose Your Own Adventure books, in which reader choices lead to multiple branching paths, yet each path is ultimately linear. Though my website will not be nearly as complex, the same premise will hold. Readers have the option to read the argument in multiple ways other than beginning to end.

Many believed that the invention of hypertext and its potential for branching narratives would fundamentally change scholarly work. It has not. The majority of historical scholarship is still written in linear books, journal articles, and essays. While great historical work has come from these mediums, their linearity limits the ways historians can present arguments as well as the ways readers can engage with them. History scholarship is not absent from the web; many digital archives have made research much easier for historians. Yet there are very few examples of scholarly historical arguments on the web other than essays that could easily be printed in a journal. My hope is that my website will be among a number of future works of multilinear historical scholarship. Yet I do not hope that such works replace books and essays, rather web arguments should work alongside them to further our understanding of the past.

Theoretically my website could be printed in an essay, but it would involve printing sections twice. Printing costs and length constraints tend to limit redundancy in books and journals, meaning most arguments are presented in one format. This is less of a concern on the web. My website will have the option for users to get a basic print version of either format, which is what I will use for peer reviews. The web argument will not even limit users to the two suggested formats. Each section will have a link on the website navigation, meaning readers can go to whatever section they want easily.

I hope that I am not the last scholar to write about William Bolin Whiteside. My original plan was to write about how the form of his property shows his ideology about landscape, but there was not sufficient archaeology at SIUE that we can tie to him. Thus far, the anthropology department has found a buckle and lead shot, which they dated to around Whiteside’s time. I am hopeful that more archaeology will be found, allowing future students and faculty at SIUE to analyze the archaeology of Whiteside. Unlike senior project papers at SIUE that are often tucked away, a website is more visible and easily accessible, allowing future scholars to look at what I’ve said about Whiteside and respond to my arguments. They too can go to specific sections of the website that are relevant to their research.

This ties to the other aspect of web writing: giving readers more freedom of interpretation. Because the web encourages more varied forms of reading, it leaves the potential for readers to come away with thoughts about the argument that the author did not necessarily intend. This may not always be an advantage for authors who wish to have control over their arguments and reader interpretations, but it is advantageous for advancing historical thought that is not tied to specific historians. I do not intend to be the last word on Whiteside and am certain that there are flaws or limitations in my theses that I am not aware of. It will be the work of future Whiteside scholars to work out these flaws and continue the historiographical process.

One way I want readers to leave with their own interpretation is in the relationship of the two theses. By showing how the two forces change over time simultaneously or separately, readers can compare what settlers are thinking ideologically to their agricultural practices and how one might lead to the other.

If we use the SIUE campus itself as an object of historical analysis on the scale of geological time, the most dramatic change would have resulted from the change from woods and prairie to farms. This would have occurred first with the rise of Cahokia around 1000 A.D., but upon the civilization’s collapse around 1300, the land returned to prairie and woods. Change began again as the French reintroduced farming near their settlements in the American Bottom, but likely farming did not reach SIUE land itself until William Bolin Whiteside arrived in 1802. Whiteside thus occupies a temporal border between a wood and prairie landscape and an agricultural landscape. Culturally, this temporal border lies between French and Indian culture and Anglo-American culture, which persists to today.

Whiteside also occupied a spatial border during his brief occupation. Geographically, the St. Louis region lies on the boundary between North American woodland and prairie, having a mixture of both. Before the Louisiana Purchase, Whiteside was near the political boundary between Spain and the United States, located at the extreme western edge of the United States. As with the temporal border, Whiteside was located on the boundary with both a French and Native American culture. The Whiteside family also pushed past the intended slave border of the Northwest Ordinance, bringing slaves with them from Kentucky, leaving Illinois as a contested boundary between free and slave states in the early 19th century. Whiteside resided in the borderlands, a fact that is central to any study of him and his contemporaries. My goal is to work out how he resolved these issues on the border between an “untamed wilderness” and “civilization.”

A warning for readers before moving forward: part of my argument relies on occasionally gruesome details of Indian attacks. In addition, some of the authors I reference, Reynolds in particular, use racist language in their description of Native Americans. While many Anglo-American settlers saw Indians as ruthless savages, I certainly do not share their views nor should they be considered an accurate account of Native Americans. Nor were Indians helpless victims of white oppression; they were diverse people who responded to European imperialism in a variety of ways, from friendly trade to outright warfare. In turn, Anglo-Americans were not moustache-twirling villains who ruthlessly slaughtered Native Americans and destroyed the environment without regret.

Whiteside was a participant in America’s two “original sins:” slavery and Native American removal and extermination. For my topic, he also played a large role in the ecological destruction of the American Bottom. It is easy to paint him as a two dimensional villain, but that is neither fair to him nor his human and animal victims. He and his fellow settlers were complex people who held mixed feelings about the changes they brought to Illinois.35 Many were sympathetic to Native Americans or were vocal opponents of slavery. No doubt some settlers regretted the loss of many wild animals. Even those who participated in Native dispossession, slavery, or ecological damage may have felt some degree of guilt but were unable to break from societal pressure, much as many in the early 21st century condemn low-wage labor but still buy clothes made in a Bangladesh sweatshop. As I will argue in my materialist thesis, many of the environmental changes were driven by the early capitalist economy beyond one individual’s control. If a male settler wanted to be successful in the community, he had to participate in the economy and, by extension, the transformation of the landscape.

Yet while I seek to understand the perspective of Anglo-American settlers, I have no interest in justifying or apologizing for their actions. Slavery, the dispossession of Native Americans, and ecological destruction are all justly condemned by 21st century America. Still, we must not allow this condemnation of actions to simplify the actors, as that prevents us from understanding either. If we better understand Whiteside and his actions, we will be better able to grapple with the lasting consequences of those actions.

From here, I recommend reading the Overview of the Illinois Frontier to get the historical context for my argument. If you are already familiar with the history of Illinois, then read the Whiteside Biography.

1. Stephen Kerber, "SIUE 50th Anniversary Historical Timeline," SIUE University Archives, 2007.

2. Probate Court of Madison County, Illinois, In the Matter of the Estate of William B. Whiteside, Deceased. Letters issued to Jacob Swiggert, 1834.

3. Louis Daguerre, Boulevard du Temple, 1838. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.

4. John Reynolds, My own times : embracing also the history of my life (Belleville: B. H. Perryman and H. L. Davison, 1855).

5. John Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois (Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1887), 416 - 417.

6.

William R. Whiteside, “The Family of William Bolin Whiteside” (unpublished manuscript), part of genealogy collection of William R. Whiteside.

7. Historian William Cronon discusses the expansion of social history to nonhuman organisms in Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, 20th Anniversary Edition. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003): 159.

8. Alex Heuer and Michael Meyer, “Digging back 250 years on the St. Louis riverfront to better learn who we are.” St. Louis on the Air. St. Louis Public Radio, MO: KWMU, August 18, 2015. 10 minutes 30 seconds mark.

10. All three images are from Wikimedia Commons: Bison, Grey Wolf, and Cougar.

11. Reynolds, My own times, 87.

13. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 169.

15. William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 159.

16. Terry Norris, “Where Did the Villages Go? Steamboats, Deforestation, and Archaeological Loss in the Mississippi Valley,” in Common Fields: an environmental history of St. Louis, ed. Andrew Hurley. (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1997), 89.

17. Cronon, Changes in the Land, 160 - 161.

18. After discussing the disappearing fowls, Reynolds states that the domesticated honeybee acts “on the reverse of the instincts of the fowls;” that they arrive with the white settlers. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illinois, 169.

19. Two works that have examined the western ideal are Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964, 2000); and Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. (New York: Vintage Books, 1950).

20. Some of these studies include Elizabeth Perkins, Border Life: Experience and Memory in the Revolutionary Ohio Valley (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Rachel N. Klein, Unification of a Slave State (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Stephen Aron, How the West Was Lost: The Transformation of Kentucky from Daniel Boone to Henry Clay (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

21. John Mack Faragher, Sugar Creek: Life on the Illinois Prairie. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), xvi.

24. Douglas K. Meyer, Making the heartland quilt: a geographical history of settlement and migration in early-nineteenth-century Illinois (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 8.

26. James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 7.

28. Reynolds, My own times, 107 - 108.

29. Reynolds, The pioneer history of Illionis., 417.

30. “Samuel Whiteside,” Illinois War of 1812 Society. (accessed March 23, 2016).

31. W. T. Norton, ed., Centennial History of Madison County, Illinois, and Its People, 1812 to 1912 – Volume 1 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1912), 134.

34. William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 99 - 104.

35. Elizabeth Perkins leaves a similar thought in Perkins, 5.

Made with Bootstrap and Glyphicons.

Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside by Ben Ostermeier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.